Table Of ContentDEDICATION

For all the musicians inspiring life and imagination through this invisible art we

call music. You spark ideas, shake the norm—and have completely changed my

life.

Thank you.

And with much love to JULIAN, MAY, and BUZZY.

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION

JIMMY PAGE

CARRIE BROWNSTEIN

SMOKEY ROBINSON

DAVID BYRNE

ST. VINCENT

JEFF TWEEDY

JAMES BLAKE

COLIN MELOY

TREY ANASTASIO

JENNY LEWIS

DAVE GROHL

CAT STEVENS

STURGILL SIMPSON

JUSTIN VERNON

CAT POWER

JACKSON BROWNE

MICHAEL STIPE

PHILIP GLASS

JÓNSI

ÁSGEIR

HOZIER

REGINA CARTER

ASAF AVIDAN

VALERIE JUNE

CONOR OBERST

COURTNEY BARNETT

POKEY LAFARGE

KATE TEMPEST

IAN MACKAYE

LUCINDA WILLIAMS

JOSH RITTER

CHRIS THILE

LEON BRIDGES

SHARON VAN ETTEN

FANTASTIC NEGRITO

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

I’ve had this love for music a long time now. This is me and my record player in Brooklyn, New York,

circa 1956. Courtesy Roy Boilen

INTRODUCTION

It’s August 15, 1965, and a cool summer night as I look toward the glowing

lights of Shea Stadium about ten miles north of me, imagining, no, wishing I was

with The Beatles. I’m twelve years old and sitting on my stoop in Queens, New

York, holding a Westinghouse transistor radio to my ear. The radio cost me five

dollars and a label from a bottle of Listerine. It is tuned to WMCA, my favorite

AM station (FM barely exists at this point). Less than two years ago, on the day

after Christmas, WMCA played “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” becoming the first

New York station to play The Beatles. The night of the Shea Stadium show, I

struggle to imagine what a concert there would be like. It is the first rock and roll

concert to ever be held at a major stadium. Approximately fifty-six thousand

people attend, including my next-door neighbor; the show sold out in seventeen

minutes (mind you, there’s no Internet).

I read the news the next day and see the black-and-white footage on TV the

following night—the screams drown out the band, the meager sound system no

competition for the level of noise produced by thousands of adoring fans, who

faint with passion, their hormones raging as they shout the names of their

favorites—John, Paul, George, and even Ringo. It’s a monumental event, and

one that will eventually pave the way for the sort of arena shows we’ll take for

granted fifty years later.

I loved, loved, The Beatles, and if I could turn back the clock to any one

night and be someplace, it would be Shea Stadium on that night.

My love for The Beatles began alongside America’s love for The Beatles,

first with their songs on the radio and then with the newscast of their arrival at

the newly renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport, a few miles from my

house. President Kennedy was shot eleven weeks before they came to America,

and I don’t believe it’s a stretch to say that our news media was happy to have

something to celebrate after so much darkness. On February 9, 1964, two out of

every five Americans turned on their black-and-white televisions to watch The

Ed Sullivan Show. The Beatles’ appearance had been booked three months

earlier, at which point no one in America knew them and their songs had never

played on American radio—in fact, you’d be hard-pressed to name any British

act with a popular song on the U.S. charts then—but by the time they arrived in

New York, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had shot to number one. Credit their

brilliant strategist and manager, Brian Epstein, and their sound, of course. I sat in

front of the television with my mom, dad, and thirteen-year-old sister, May, and

thought it was the most thrilling music my ten-year-old ears had ever heard. The

Beatles were vibrant and young, none older than twenty-three, and on that night

our screens filled with rock and roll, a departure for the normally tame variety

show, which often featured Broadway singers, acrobats, comedians, and a

magician doing a saltshaker trick.

Punk is often credited with shaking up the music world, while we tend to

view the British Invasion—the wave of British bands that followed in the foot-

stomping steps of The Beatles—as cute and adorable. But everything about

music changed after those Brits arrived. Sales of records and record players hit

all-time highs, much of the teenage world bought guitars, and your next-door

neighbor’s garage was as likely to house a budding band as an Oldsmobile. In

1958, guitar sales in the U.S. totaled approximately three hundred thousand; by

1965, barely one year into the British Invasion, that number had exploded to one

and a half million. The guitar replaced the piano as the main instrument in

popular music. My sister and I took lessons—me with the intent to learn all The

Beatles’ songs. I struggled with the instrument, and my teacher later told my

mom that I had no musical ability. I was crushed. Instead, I spun 45s endlessly in

my bedroom, pretended to be a DJ, created secret make-believe pop charts, and

fell deeply in love with music. When I wasn’t in school, I always carried two

items: my trusty transistor radio and a stickball bat. I lived for baseball and

records. At night, I hid my radio under my pillow and listened to either New

York Yankees games or rock and roll. My friends were The Zombies, The

Kinks, The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Beau Brummels, The Beach Boys,

The Byrds, The Yardbirds, and so many others. I bought my first album, Meet

The Beatles, at the radio and television repair shop at the local shopping center

in Lindenwood, and often walked all the way to the Times Square department

store to purchase my 45s.

I was raised in a middle-class family in a working-class neighborhood that

consisted mostly of Italians and Jews. I was the latter. My dad, Roy Boilen, sold

frozen meat and frozen food and the freezers to store them in. My mom, Buzzy,

worked the phone, canvassing families and arranging appointments for my dad.

He traveled a lot and wasn’t home much during the week, but when he was, he

listened to big band music. Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Glenn Miller

made him happy. I recall visiting his parents’ house and listening to old 78s in

the basement. It is a world of music I came to appreciate only much later. My

mom loved show tunes and Barbra Streisand, music that I never came to

appreciate: to this day it drives me up the wall, though my sister recently

reminded me of my obsession as a six-year-old with the Broadway cast album

for Flower Drum Song.

Some time around 1965, my dad bought a fancy stereo sound system, with a

nice Scott FM tube receiver and some snazzy speakers, which I blew up about

five years later listening to the deep synthesizer music of Emerson, Lake &

Palmer at high volume. The year 1966 saw the evolution of FM radio, and that

too changed everything. DJs like Alison Steele, Rosko, and Scott Muni, among

others, started playing what they loved rather than music they were told to

program. For a kid like me, the shift from AM, with its low quality and

screaming commercials, to the low-key and high-quality sound of FM was mind-

blowing. I think it’s fair to assert that the development of FM was as

revolutionary to the world of music as the one we’ve seen in the twenty-first

century with the transition from CDs to digital downloads and now online

streaming. With the advent of FM, music that catered to particular tastes rather

than mass appeal had a home. It was the first time I heard The Velvet

Underground, and it was the beginning of “underground” music, later called

“alternative,” later called “indie.” The thread is long, but the aesthetic is the

same—music as art, not commodity.

By 1966 technology made the recording process more expressive and the

listening process more trippy (so did the drugs). Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling

Stone” (1965) and The Doors’ “Light My Fire” (1967) were short songs on the

AM dial, but twice as long and twice as interesting on FM. It was also a year of

mind-altering albums, including The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, The Beatles’

Revolver, Bob Dylan’s double album, Blonde on Blonde, The Mothers of

Invention’s Freak Out!, and The 13th Floor Elevators’ The Psychedelic Sound of

The 13th Floor Elevators. Albums began to have concepts; no longer were they

simply vehicles for hit songs. In fact, The Beatles released numerous hit singles

that didn’t even make it onto the UK editions of their albums, such as “We Can

Work It Out,” “Day Tripper,” “Penny Lane,” and “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

In the summer of 1967, I went to my friend Alan’s house. He’d just returned

from the record store and played for me the most mind-boggling, beautiful

album I’d ever heard: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. If you’re not as

old as I am, it’s important to note that music had never sounded like this before.

Imagine growing up in a city and walking into a forest for the first time—that’s

what the experience of this album was like for me. We sat and listened to

swirling, unidentifiable sounds from India, vaudeville, the circus, the farm, the

classical concert hall, all otherworldly and newly created. We stared at the

colorful cover art, a collage of people, some real, some fictional, known and

unknown. The gatefold opened to a photograph of a band we recognized, but one

that was also deeply changed, adorned by beards, mustaches, and bright red,

green, pink, and blue, nearly Day-Glo military uniforms. Best of all, the lyrics

were printed on the back cover, something I’d never seen before, so we could

follow along word for word. It was an adventure, a journey, and—to steal a term

from the day—a trip. For me, the album’s closing track, “A Day in the Life,”

was the most startling of all. It’s a song that changed my life forever. The lyrics

are both straight storytelling and impressionism, pedestrian and poetic. It was

two completely different songs sonically melded into one, opening with John

Lennon’s simple strumming of an acoustic guitar as he tells a tale inspired by

two different newspaper articles, one about four thousand potholes to be repaired

on the streets of Blackburn in Lancashire, the other about the death of Tara

Browne, an heir to the Guinness brewery fortune, in a high-speed car crash.

He blew his mind out in a car

He didn’t notice that the lights had changed

A crowd of people stood and stared

They’d seen his face before

Nobody was really sure

If he was from the House of Lords.

The lyrics were the result of the important and often disputed collaboration

between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Lennon admitted that Paul added the

line “I’d love to turn you on” as a bit of a poke at the stiff-upper-lip British

establishment. And Paul also had a bit of tune he was working on that didn’t

have much to it and that somehow found its way into the song, almost as a

counterpoint to the poignant, impressionistic words sung by John. Paul sings:

Woke up, fell out of bed,

Dragged a comb across my head

Found my way downstairs and drank a cup,

And looking up I noticed I was late.

Found my coat and grabbed my hat

Made the bus in seconds flat

Found my way upstairs and had a smoke,

Somebody spoke and I went into a dream.

But it’s the orchestral chaos that really takes this song to a whole new level.

It’s massive. It builds and builds, based on an idea producer George Martin

claims Lennon gave him. In All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles

Release, Martin recounts the moment: “What I’d like to hear is a tremendous

buildup, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world.”

Martin hired an orchestra and recorded them multiple times, then mixed it all

together, the equivalent of something like 160 musicians. That day, I left Alan’s

house floored, bought my own copy, and listened to it every day in whole or

parts for years. To this day, I am astounded at the progression of this band from

their first recordings in 1963 to what they accomplished by album number eight,

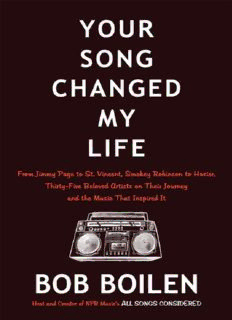

Description:"Bob Boilen’s book gets at something real and rare about the power of music."—New York Times Book ReviewFrom the beloved host and creator of NPR’s All Songs Considered and Tiny Desk Concerts comes an essential oral history of modern music, told in the voices of iconic and up-and-coming mus