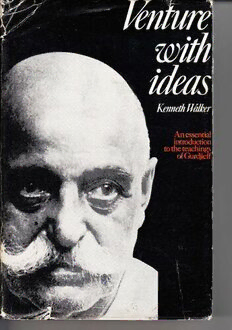

Table Of ContentIn 1923 Kenneth Walker met a

man who was destined to exert

an immense influence over his

life, P. D. Ouspensky who, in

turn, had learnt his knowledge

from Gurdjieff.

This book, first published in

1951 and out of print for many

years, sets out to give an

account of the impact of this

knowledge on a man who had

received an orthodox scientific

education and who was in no

way a searcher for esoteric

truth. It is a chronicle of a

journey through the bewildering

inner world of ideas, a journey

made by the author with two

remarkable men. It is a search

for truth.

Venture with Ideas has

undoubtedly an important

message for humanity in this

critical period of its history.

Jacket design by

EVE BLOOMFIELD

SBN 85435 291 0

VENTURE

WITH IDEAS

by

KENNETH WALKER

£ •

NEVILLE SPEARMAN

LONDON

FIRST PUBLISHED 1951’

THIS EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1973

BY NEVILLE SPEARMAN LIMITED,

I 12 WHITFIELD STREET, LONDON WIP 6dP

BY ARRANGEMENT WITH JONATHAN CAPE LTD

© KENNETH WALKER 195 I

SBN 85435 291 O

Dewey Classification

149-3

:

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

REDWOOD PRESS LIMITED, TROWBRIDGE, WILTSHIRE

USING CAXTON ANTIQUE WOVE SUPPLIED BY

FRANK GRUNFELO LTD., LONDON

BOUND BY MANSELL BOOKBINDERS LTD., LONDON

CONTENTS

F O R E W O R D

T nis book requires an explanation and it is in the

foreword that this should be given. In 1946 my

publishers were good enough to re-issue a book of

mine which, written and published several years previously

under the title of The Intruder, was both out of print and out

of date. It reappeared under a fresh name after having

been largely rewritten. To cursory readers the new book, I

Talk of Dreams, appeared to be only a rather light-hearted

autobiography but those with more discernment realized

that its autobiographical details were only incidental and

that it was primarily a study in psychology. My motive in

writing it was clearly enunciated on the first page, where the

following passage occurred: ‘This book is a record of some

of the writer’s own mechanisms. Like a teacher of biology

1 illustrate the laws of living by showing them at work on

the actual animal, but in this case I am not only the demon

strator but the object which he demonstrates. In short, I

am my own rabbit.’ A condition had been attached by

Jonathan Gape to the re-issuing of my former work, namely,

that it should be brought up to date; instead of ending in

1925 as The Intruder had done, the new book should end in

the year 1946.

What could be more reasonable and natural than this

condition and yet it was one which it was impossible for me

to fulfil. In 1923 I met a man who was destined to exert an

Immense influence over my life, P. D. Ouspensky, the author

of Terlium Organum and A New Model of the Universe. Ouspen-

■ ky was well known as a writer but what was not generally

known was that he was also the exponent of a special system

ol knowledge which he had previously learnt from Gurdjielf.

I attended the private meetings at which he expounded this

teaching from 1923 till 1947s the year of his death, and I gave

9

FOREWORD

him the promise which he exacted of all his followers, namely,

that nothing that was learnt at his meetings should be

spoken about in public or allowed to appear in print. How

then could I possibly bring my autobiography up to date

and at the same time leave out of it what was of such great

importance to me, the system of knowledge I had obtained

from Ouspensky? My publishers, without knowing the real

reason for my difficulty, were so considerate as to rescue me

from the dilemma in which I found myself by waiving the

condition they had made.

The recent publication of Ouspensky’s and Gurdjieff’s

books, In Search of the Miraculous and All and Everything, have

now freed me from my old promise and I am at liberty to

reveal what previously had to be kept silent. There is no

further need for me to stop abruptly in the development of a

line of thought because it begins to encroach on ideas I

learnt from Ouspensky. I am no longer obliged to erase

from time to time what I have already written on the grounds

that it has a too close affinity to Ouspensky’s teaching. For

the first time for well-nigh thirty years I am free to write

whatever I care to write and I am conscious of a new and

unaccustomed sense of freedom. In my opinion the system

of knowledge taught by Ouspensky and Gurdjieff is of such

value that it merits the widest possible publicity and it is

this conviction of mine which has prompted me to write this

present book. I have called it Venture with Ideas on the

grounds that a venture is an enterprise on which the adven

turer sets out without being able to foretell what will be its

outcome. The voyage of discovery on which I embarked

light-heartedly nearly thirty years ago was certainly of this

nature and it has proved to be as rich in unexpected incidents

and hazards as the journey I made as a younger man

through what at that time was a little-known part of Africa.

For it is a grave mistake to look upon ideas as passive

instruments of the mind which we can use for a period and

io

FOREWORD

then, when we have grown tired of them, throw aside. They

are powerful agents capable of taking possession of us and of

propelling us in a direction in which, at the beginning, we

had no desire to go. There are ideas so powerful indeed that

they are capable of destroying us body and soul, as the

speculations of Engels and Marx and the idea of the sanctity

of the state have destroyed many men and women who have

been rash enough to lend them their credence. It is because

I now realize how potent are the ideas I received from Ou-

spensky and Gurdjieff that I look upon my past association

with these two remarkable men as having been a great

psychological hazard. Venture with Ideas is therefore an

appropriate title for the book that is to follow.

It is not my intention to give an account of Gurdjieff’s

system of knowledge and for two reasons. The first is that

knowledge of this kind is imparted orally and in accordance

with the standing of the pupil. The second is that those

ideas in Gurdjieff’s system of knowledge which are of a more

general nature have already been published in Ouspensky’s

book, In Search of the Miraculous and in Gurdjieff’s own

allegorical work, All and Everything. It is to these that the

reader must therefore turn if he requires more detailed

information on the subject of Gurdjieff’s teaching. I have a

different object in writing this book. It is to give an account

of the impact of this knowledge on a man who had received

an orthodox scientific education and who was in no way a

searcher for esoteric truth, the man in question being myself.

The very term ‘esoteric truth’ would have elicited a smile

or a shrug of the shoulders had it been uttered in my presence

prior to my meeting with Ouspensky. Like Bertrand Russell,

a far cleverer person than myself, I believed that the scientific

method was the only instrument by which it was possible to

discover truth. The idea that there existed an underground

trickle of knowledge which from time to time made its way

to the surface and then plunged underground again would

11

FOREWORD

have appeared to me to be utterly fantastic. Yet when I now

look back at the history of Western knowledge and note the

appearance from time to time of some teacher who gathers

around him a circle of disciples, imparts knowledge to them

for a few years, and then either dies or disappears, I see no

way of explaining these events other than by the term

‘esoteric knowledge’. I am referring to such teachers as

Pythagoras, Appoionias of Tyana, Ammonius Sacca, the

teacher of Plotinus, St. Martin, generally known as ‘le

philosophe inconnu, and a long line of other men whose

names have now been forgotten. And the fact that the

memory of these teachers of esoteric truth so rapidly fades

is the second and more important reason for my under

taking this book. I wish to give an account of a modern

representative of this long line of teachers, of a man known

only to a comparative few and who in his own book gives

the following description of himself. ‘He who in childhood

was called “Tatakh”; in early youth “Darky”; later “the

Black Greek”; in middle age, the “Tiger of Turkestan”; and

now, not just anybody but the genuine “Monsieur” or

“Mister” Gurdjieff, or the “nephew of Prince Mukransky”,

or finally, simply a “Teacher of Dances”.’

It is therefore to Gurdjieff, the most astonishing man I

have ever met, the man from whom I have learnt more than

from any other person, that I dedicate this book. To end

this foreword with the customary Latin tag, ‘Requiescat in

pace would be singularly inappropriate. To whatever

sphere Gurdjieff s spirit has been called, it does not rest

there, but continues instead the struggle which it began long

ago upon earth, the struggle to reach a higher level of being.

Little London

1950

12