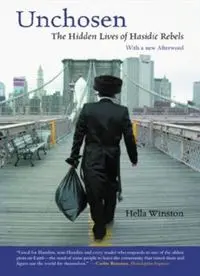

Table Of ContentUnchosen

The Hidden Lives of Hasidic Rebels

Hella Winston

Beacon Press, Boston

Beacon Press

25 Beacon Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892

www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books

are published under the auspices of

the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

© 2005 by Hella Winston

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

09 08 07 06 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper

ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992.

Text design by Bob Kosturko

Composition by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Winston, Hella.

Unchosen : the hidden lives of Hasidic rebels / Hella Winston.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8070-3627-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Jews—New York (State)—

New York—Biography. 2. Hasidim—New York (State)—New York—

Biography. 3. Hasidim—New York (State)—New York—Social conditions.

4. New York (N.Y.)—Religion. I. Title.

F128.9.J5W55 2005

305.6'968332'097471—dc22

2005007929

In memory of my grandparents,

Salamon and Hella Schönberg

Contents

Introduction vii

Chapter One: Changing Trains 1

Chapter Two: Wigged Out 19

Chapter Three: Floating 37

Chapter Four: From the Outskirts 49

Chapter Five: Coming and Going 61

Chapter Six: Building a Different Kind of Chabad House 71

Chapter Seven: Becoming a Rock Star 87

Chapter Eight: Second Acts 101

Chapter Nine: Dancing at Two Weddings 117

Chapter Ten: A Cautionary Tale 133

Chapter Eleven: L’Chaim 147

Conclusion 165

Afterword 172

Glossary 177

Acknowledgments 183

Notes 185

The nature of the subject matter of this book required me to change

the names and certain aspects of the characters who appear on its

pages, with the exception of Malkie Schwartz, whose name is her

own. In some cases, elements of particular events were changed as

well. These changes were made solely to protect the privacy of those

who, in many cases, took serious risks to share their stories. These

changes, however, do not alter the essential truth of their experi-

ences, or their thoughts and feelings about those experiences.

Introduction

As I glance around the large dining room table, I am struck by just

how oddly familiar these women seem to me, although I have never

actually met any of them before. They are all members of the ex-

tremely insular Satmar Hasidic sect. Socializing with a secular Jew

like me—let alone having one in their home for a meal—is some-

thing most would do only under very unusual circumstances, if at

all. The women are all dressed modestly, in long skirts, thick stock-

ings, high-necked sweaters, and monochromatic cloth turbans that

expose no hair. But, despite their dress, and their frequent lapses into

Yiddish I can only intermittently understand, there is something

about these Satmar women that reminds me of some of the women

in my extended family, even several of my friends. Is it in their fea-

tures, I wonder? There is, after all, great variety here: a few have dark

eyes and olive skin, while others are fairer, with freckles, or blue

eyes. Perhaps it’s something less tangible or purely physical—like

the forceful, animated way they are speaking over one another, or

their constant concern that I have enough food on my plate.

Whatever it is, I do know that after so many frustrating weeks of

trying to find a way into this community for my doctoral disserta-

tion in sociology, I am excited, and more than a little nervous, to be

sitting here. Of course, I was prepared for how difficult gaining ac-

cess would be, given what I had read and heard about how fervently

the Satmarers seek to avoid contact with outsiders. If I wanted to

meet Hasidic people, I was told repeatedly, I should go to Crown

Heights. There, Lubavitchers zealously court the opportunity to in-

troduce unaffiliated Jews to the beauty of “true” Judaism.

vii

viii Int roduc t i on

Indeed, a good many popular accounts of Hasidic Jews have fo-

cused on Lubavitch. Several Jewish journalists and scholars have pro-

duced largely admiring books describing the compelling Lubavitch

1

philosophy, way of life, and formidable outreach efforts. With its

“mitzvah tanks,” campus Chabad houses, celebrity-studded fundrais-

ing telethons, and outposts across the globe, Lubavitch has become

almost synonymous with Hasidism. This despite the fact that in the

2

United States it numbers less than half the size of Satmar and is

hardly representative of the Hasidic community as a whole. With

their mission—unique in the Hasidic world—to attract unaffiliated

Jews, Lubavitchers are raised to engage with ( Jewish) outsiders, do-

3

ing missionary work wherever Jews are found around the world. As

4

Sue Fishkoff so vividly documents, however, Lubavitch missionar-

ies do this apparently without compromising their strictly Orthodox

way of life.

This emphasis on proselytizing has meant that a significant per-

centage of Lubavitchers were not born into the community, but

joined by choice. Often those who join, known as baalei teshuvah

(“masters of return”), have led formerly secular (or at least non-

Orthodox) lives, which likely included a college education or be-

yond. In fact, in her book on Lubavitch girls, Stephanie Wellen

Levine asserts that in the year 2000, 70 percent of the Lubavitch

5

girls’ school’s graduating class came from baalei teshuvah homes.

This focus on proselytizing has, understandably, fueled much of

6

the interest in this group. Additionally, Lubavitch raises a substan-

7

tial amount of money from non-Hasidic Jews, —including Revlon

billionaire Ronald Perelman and cosmetics mogul Ronald Lauder

—who apparently support its mission without any intention of com-

mitting to the lifestyle. All of this is in strong contrast to the other

Hasidic sects, which include Satmar, Ger, Viznitz, Belz, Bobov,

Skver, Spinka, Pupa, and Breslov, to name only a few. In these sects,

almost all members are born into the community, and none engages

in formal outreach, making them comparatively more insulated

from, and less aware of, the ways of the outside society than their

counterparts in Lubavitch.

Int roduc t i on ix

It was precisely for these reasons that I did not want to go to

Crown Heights. While Lubavitch’s openness to even the most sec-

ular Jew would have made gaining access to that community fairly

easy, it was, to a great extent, the self-imposed insularity and segre-

gation of the Hasidim that had made me so interested in them to

begin with. Also, given that so many Lubavitchers join that com-

munity by choice, I felt that any in-depth inquiry into the daily life

of Lubavitch would require both an exploration of the motivations

and experiences of such people, and a consideration of the effect of

this phenomenon on the group as a whole—tasks I was not prepared

to undertake. Further, I was concerned that the Lubavitch interest

in and skill at proselytizing—not to mention its apparently sophis-

ticated PR operation—might actually make it more difficult for me

to get a complete picture of what everyday life was like in that com-

munity. Groups that are trying to attract potential members, even

those with the purest of intentions, are not apt to expose such peo-

ple to anything that might undermine this goal.

As a result, I decided I would try to find a way into one of the

other communities, and it was ultimately through a doctor friend in

Brooklyn with a large Hasidic practice that I made contact with Suri,

a Satmar woman and my hostess for this evening. When the doctor

first agreed to tell Suri about my interest in meeting Hasidic people,

and to give her my telephone number, I hadn’t actually expected her

to call. After all, Satmar is considered to be the most insular and

8

right-wing of all the Hasidic sects, and anti-Zionist to boot. But, to

my surprise, Suri did call, and our first conversation over the phone

lasted close to an hour. Before we hung up, Suri told me that she

would like to have me to her Brooklyn home for dinner. She wanted

me to meet some of her closest friends—all women deeply involved

9

in the life of their community. I felt as if I had struck gold.

I was impressed, during that initial call, by Suri’s apparent

warmth and openness, her sense of humor and sophistication. She

seemed to have traveled widely, and she held a demanding job in the

community—something that, while by no means unheard of, is still

not the norm for Hasidic women, given their tremendous responsi