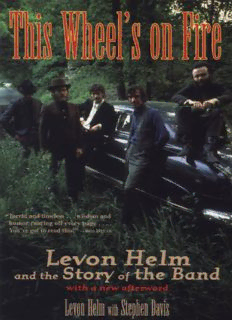

Table Of ContentTHIS WHEEL’S ON FIRE

LEVON HELM

AND THE STORY OF THE BAND

LEVON HELM WITH STEPHEN DAVIS

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Helm, Levon.

This wheel’s on fire: Levon Helm and the story of The Band / Levon Helm

with Stephen Davis.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-55652405-9

1. Helm, Levon. 2. Rock musicians—United States—Biography. 3. Band

(Musical Group). I. Davis, Stephen. II. Title.

ML419.H42A3 1993

782.42166′092′—dc20

[B]

93-4413

CIP

MN

Copyright © 1993 by Levon Helm and Stephen Davis Afterword copyright ©

2000 by Levon Helm and Stephen Davis All right reserved.

Originally published by William Morrow and Company, New York.

This edition published by A Cappella Books An imprint of Chicago Review

Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-55652405-9

Printed in the United States of America

15 14

Isn’t everybody dreaming!

Then the voice I hear is real

Out of all the idle scheming

Can’t we have something to feel.

“IN A STATION”

RICHARD MANUEL

CONTENTS

Prologue Time to Kill

Chapter One The Road From Turkey Scratch

Chapter Two The Hawk (Out for Blood)

Chapter Three Take No Prisoners

Chapter Four Levon and the Hawks (One Step Ahead of Land of 1000

Dances)

Chapter Five Dylan Goes Electric

Chapter Six Something to Feel

Chapter Seven The Band

Chapter Eight Divide and Conquer

Chapter Nine The Last Waltz

Chapter Ten The Next Waltz

Afterword The Most Fun I’ve Had So Far

Acknowledgments and Sources

Index

Prologue

TIME TO KILL

The Band had always had a pact that if one of us died on the road of a heart

attack or an overdose or a jealous boyfriend, or whatever might kill a traveling

musician, the others would put him on ice underneath the bus with the

instruments and haul him back to Woodstock before the police started asking

questions. This flashed through my mind as I ran half-dressed down the motel

corridor at nine o’clock on the morning of March 4, 1986, in Winter Park,

Florida.

Richard Manuel and I had been laughing for years at stuff that wasn’t even

funny anymore, when he went and took his own life. We were on what had been

jokingly called the “Death Tour” because the gigs were in small places hundreds

of miles apart. We tried to approach it with good humor, but I know Richard felt

we weren’t getting the kind of respect we were used to. This was ten years after

The Last Waltz, fifteen years after we were playing the biggest shows in

American history, twenty years after Bob Dylan had “discovered” us, and

twenty-five years after Ronnie Hawkins had molded us into the wildest, fiercest,

speed-driven bar band in America. It had been almost thirty years since I’d left

my daddy’s cotton farm in Phillips County, Arkansas, to seek my fortune on the

rockabilly trail.

For sweet, ultrasensitive Richard Manuel, the trail ended on a spring morning

in Florida.

Richard’s wife, Arlie, was screaming hysterically, “He’s dead! Oh my God,

he’s dead!” Rick Danko and his wife, Elizabeth, were already in Richard’s

room, and I heard Rick kind of gasp and say, “Oh, no, man …” I went inside:

The room was in disarray, the bed unmade, the TV on, an empty bottle of Grand

Marnier on the dresser. The light was on in the bathroom. Suddenly I got a

terrible sense of pure dread and felt surrounded by the chill of death. I wanted to

run the other way as fast as I could, but instead I walked to the bathroom door

and looked in.

What I saw just broke my heart. That’s for damn sure. It would’ve broken

yours too.

Five days later Rick and I and Richard’s brothers carried his metal casket into

Knox Presbyterian Church in Stratford, Ontario. Richard had been raised a

Baptist, but the bigger church was needed to accommodate his last sold-out

show. The organist was Garth Hudson, who set the tone of the service with his

old Anglican hymns. My mind was wandering through the prayers and the

Scripture readings. Jane Manuel, Richard’s ex-wife, and her children were there,

dozens of Richard’s relations, and many friends from our days in Toronto. It was

hard to see so many beloved sad faces on such an occasion. I never did like

funerals.

Robbie Robertson had been asked to deliver a eulogy, but he didn’t show up.

Friends of Richard’s remembered his laughter, his jokes, his scary driving, his

love for music. Then Garth played “I Shall Be Released,” which Bob Dylan had

written for Richard to sing. Through all three verses there wasn’t a dry eye in the

church.

I had a funny experience while Garth was playing. I was thinking about

Richard and asking myself why, when I clearly heard Richard’s voice in the

middle of my head. It came in as clear as a good radio signal. And he said,

“Well, Levon, this was the one action I could take that was gonna really shake

things up. It’s gonna shake ’em up and change things round some more, because

that’s what needs to happen.”

Now, to understand this—and I think I have come to an understanding—you

would have to know what Richard had been through, although that would be

hard to convey. In fact, you’d have to know what we all had been through: the

story of The Band, from 1958 until today. Because from then to now we went

through the best of times as well as times that were full of pain and

disappointment. But those bad times are important. They give you a chance to

practice, listen, take stock, have a life, get your feet back on the ground, and

maybe you’ll live to tell the story.

That’s what this book is all about. My story is recalled and written from my

perspective on the drum stool, which I’ve always felt was the best seat in the

house. From there you can see both the audience and the show. Along the way

we’ll check in with friends and family, and I thank them for their memories and

the ability to share them. In the end, though, the story must be my own, with

apologies in advance to those I neglect to mention or damn with faint praise.

Memory Lane can be a pretty painful address at times, but in any inventory of

five decades of American musical experience you’ve got to take the good with

the bad. So draw up a chair to my Catskill bluestone fireplace while I roll one,

and we’ll crack open a couple of cold beers. The game’s on the cable with the

sound off, and I’m gonna take you back in time, specifically to cotton country:

the Mississippi Delta just after World War II. We’re gonna get this damn show

on the road.

Chapter One

THE ROAD FROM TURKEY SCRATCH

Waterboy! Hey, waterboy!

That’s my cue. It’s harvesttime, 1947, and I’m the seven-year-old waterboy

on my daddy Diamond Helm’s cotton farm near Turkey Scratch, Arkansas. My

dad and mom are working in the fields along with neighbors and black

sharecropping families like the Tillmans and some migrant laborers we’d hired,

seasonals up from Mexico. My older sister, Modena, is back at the house

watching my younger sister, Linda, and my baby brother, Wheeler. Since I’m

still too young for Diamond to sit me on the tractor, my job is to keep everyone

hydrated. I got a couple of good metal pails, and I work that hand pump until the

water runs clear and cold. I run back and forth between the pump house and the

turn row, where the people drink their fill under a shady tree limb. I learned

early on that the human body is a water-cooled engine.

It was hard work. The temperature was usually around a hundred degrees that

time of year. But that’s how I started out, carrying water to relieve the scorching

thirst that comes from picking cotton in the heat and rich delta dust.

I was born in the house my father rented on a cotton farm in the Mississippi

Delta, near Elaine, Arkansas. The delta is a different landscape from the one you

might be used to, so I want to draw you some sketches of the old-time southern

farm communities I grew up in, when cotton was king and rock and roll wasn’t

even born yet.

I’m talking about a low, flat water world of bayous, creeks, levees, and dikes,

and some of the best agricultural land in the world for growing cotton, rice, and

soybeans. When the first Spanish explorers arrived in the sixteenth century, the

delta’s cypress forests sheltered Mississippian Indian tribes—Choctaw,

Chickasaw, Natchez—who constructed giant burial mounds related to astronomy

and magic. I’m descended from them through my grandmother Dolly Webb,

whose own grandmother had Chickasaw blood, like many of us in Phillips

County.

In the 1790s Sylvanus Phillips led the first English settlers across the

Mississippi River into eastern Arkansas. They were mostly immigrants from

North Carolina, the Helms probably among them. They laid out the town of

Description:The Band, who backed Bob Dylan when he went electric in 1965 and then turned out a half-dozen albums of beautifully crafted, image-rich songs, is now regarded as one of the most influential rock groups of the '60s. But while their music evoked a Southern mythology, only their Arkansawyer drummer, Le