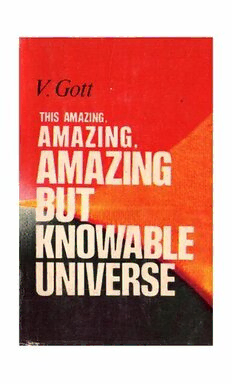

Table Of ContentV. Gott

THIS AMAZING,

AMAZING,

AMAZING

BUT

KNOWABLE

UNIVERSE

Progress Publishen

Moscow

Trans1ated from the Russian

Ьу John Bushnell and Кrlstlne BushneП

Designed Ьу Inпa Borfsova

в. с. rотт

УДИВИТЕЛЬНЫЙ. НЕИСЧЕРПАЕМЫЙ,

ПОЗНАВАЕМЪIЙ МИР

На английском лзыке

First printing 1977

© Издательство <<Знание~>, 1974

@ Translation into English. Progress PuЫishers 1977

Printed in the Union of Soviet SociaJist RejJuhlic1

i0502-8!6

r 62 77

014(01)-11 -

CONTENTS

Introduction • • • . • • . . . • . . • S

Concepts, Categories, Cognition. • • . • • • 21

Matter and Motion • • • • • • . . • • 40

The Uncreatedness and Indestructibility of Matter • • 63

On the Inexhaustibility of Moving Matter. . . . . 80

The Laws of Conservation in Modern Physics . . • . . tOl

The Reflection of the Continuity and Discontinuity of the

Material World in Cognition , . . . . . . . . . 142

The Principle of Symmetry and Its Role in Cognition . . . 158

The Principles of Phyi;ics and Their Place in Cognition 180

The Dialectic of the Absolute and the Relative . . • . . 222

Conclusion . • • • • . . . . . • • .. . . . . 2114

INTRODUCTION

An enormous, fascinating and to a)arge extent

unknown world surrounds man from the first moments

of his existence down to the moment when he draws his

last breath. Resting on preceding generations'

advances in science and culture, each new generation

makes its own contribution to our knowledge of the

unknown�

The more inan knows, the more clearly he

understands that there is still something unknown to

be sought, for example, in atomic nuclei, in the

structure of "elementary'' particles, in the deeps of

space, in the depths of' the Earth; that we need to

uncover the secret of the origin of life from non-life, to

grapple with many unsolved problems.

The presence of the unknown gives rise to two i

contradictory fele ings: pessimism in some, optimism (

in others, and this makes the question of the world's l

cognizability most relevant. However, this question '

passes beyond the limits of natural sciences into the

realm of philosophy.

We should ·immediately make clear the sort of

philosophy we are referring to. In the history 9f

philosophy, millennia passed before the pre-scientific

philosophy of Babylon, Egypt, An�ient Greece,

MediaevaJ Europe, of the 18th and the first half of the

s

19th centuries, was supplanted by the scientif1c

philosophy of Marxism-Leninism. There is nothing in

this assertion to belittle what was done by the great

philosophers of the past-Democritus, Plato, Aristotle,

Descartes, Spinoza, the French materialists of the 18th

century, Kant, Hegel, Feuerbach and many others. We

have something else in mind. Even the most brilliant

pre-Marxist philosophers were limited in their work by

the historical framework within which they lived; they

could not create a scientific philosophy. Only after

capitalism had become the dominant economic system

in a number of European countries and the proletariat

had emerged into the historical arena as a class able

not only to free itself from exploitation but also, by

·means of revolutionary upheaval, to eliminate the

exploitation of man by man, only when the natural

sciences began to advance rapidly, were the necessa,nr

conditions present for the emergence of a scientific

philosophy that could serve as the theoretical basis for

the world outlook of the most progressive class in

huma n history-the working class.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, generalizing from

the experience of the workers' movement and the

achievements of natural science, and making use

of-and critically reworking-the best of earlier

philosophy, worked a major revolution in philosophy,

creating the philosophy of dialectical materialism,

which is a creative, developing doctrine on the most

general laws of nature, human SOFiety and thinking.

After Marx and Engels, scientific philosophy was

further developed in the works of V. I. Lenin, his

followers and disciples and in the documents of

Communist and Workers' parties throughout the

world.

In order to explain to the reader the idea of this

book, I shall permit myself a short digression of a

personal nature. While still quite young, my attention

6

was caught by many phenomena in nature and social

. life, and I sought for explanations in books on phy

)sics, astronomy, chemistry, biology and the 4istory of

the ·workers' movement; I also became interested in

archaeology, the history of art, philosophy and 'o/Or�d

history. I read unsystematically Orest Khvolson, Elisee

Reclus, Camille Flammarion, Francis W. Aston, and

Plato, but only when I read Engels' The Developmef!,t

of Socialism from Utopia to Science at age 15, and

..

somewhat later Leriin's Materialism and Empirio·

Criticism, did I alize that it was necessary to.select a

re

clearly delimited range of questions to .the study of

which one should dedicate �>ne'slife. I understood, too,

and.. . subsequent__years conflml.ed it, thaj intense study

of finite scientific problems is most efI�tive_.given a

brpad approach, on the basis of th� general

· .

methodology of Marxism-Leninism. Since that time

the .study of the natural sciences and phil9sophy have

·

for me been a single process.

·

·.Many years later, I came across a remark by the

well-known French physicist, Paul �Langevin, which

beautifully expresses the naturalist's relationship to

¥arxism-Leninism. Speaking in December· 1938 at

a

conference of the French. Communi�t Party; Langevin

..

said:

"To your Party has ·fallen the honor .pf closely

uniting thought and action.

"A Communist, it is said, must constantly learn. I

want to say that the more I learn, the more I feel myself

· ·

a Communist.

"In the great communist doctrine developed by

.

Marx, . Engels and. Lenin I found the ·answer to

.

questions relating to my own science, and I would

never have found it without this doctrine�

"1

1 W.,dd Maubt Review, No. 2, February 1972, p. 45.

7

At fttst independent study of some of the Marxist·

Leninist classics, especially on philosophy, and then

systematic ,study of them at the university level, helped

me, as it did many of my colleagues, to carry out

research in the physics of the atomic nucleus., a

. problem with which I was concerned for more than ten

years, and then-in other research.

The son of a worker and myself a worker in 1930,

,

�fter completing the workers' courses I entered the

first year of the newly established department of

physics and mechanics at the Kharkov Mechanical and

Engineering Institute, simultaneously beginning work

at the Ukrainian Institute of Physics and Technology

UPT), which had opened in the same year.

Young physicists from Leningrad · formed the

nucleus of the Ukrainian IPT. Under their benevolent

influence theoretical and experimental physics began

,

to make rapid strides in the Ukraine. The personnel

constituted a harmonious, · international research

group. The Leningrad physicists L. Landau,

I. Obreimov, A. Leipunsky, K. Sinelnik.ov, A. Valter,

V. Gorsky, L. Shubnikov among others, in addition to

,

carrying out an immense amount of research, began to

train physicists for the research institutes and industry

of the USSR, the Soviet Ukraine included.

There was only a slight difference in age between

ourselves"---Students and laboratory assistants-and our

professors and academic ad.visors. In 1933, when

Landau taught our course on theoretical physics, he

was only 25; Leipunsky was 30, Valter 28; the students

in my group-Evgeni Lifshits and Aleksandr

Kompaneyets among others-e.nd I were between 18

and 20. We were together during lectures and lab

assignments in the department during research work

,

in· the Ukrainian IPT, and took part in sports and

excursions together. We often discussed current issueS'

in physics and philosophy, literature and art, and

problems in domestic and international life

.

s

The situation in the Institute in those years was

conveyed well by a newspaper article "IIlgh-Voltage

Komsomol Lab", published September 1, 1933. The

article deals with the atomic ("high-voltage")

laboratory where pioneering work was being done in

breaking down the nuclei of a number of chemical

elements and in the search for peaceful ·ways of using

the enormous resenres of intra-nuclear energy.

"The high-voltage Komsomol team bombards the

atomic nucleus in order, like the Soviet Union, qaving

destroyed the o�d to create the new, magnificent,

enormous and fine. ... This young cluster of Soviet

scientists is marked by its multiplicity of qualities:

Russian revolutionary sweep, American practicality,

the concentrated focus of the German scientist and the

buoyancy of the very young man who sees his goal and

has the opportunity to reach it.'' Reporting the

research being conducted in the laboratory, the

newspaper wrote: "The work would go badly without

the activity of the students Taranov, Vodolazhsky,

Gott and Marushak, who have put together all of the

high-voltage circuitry. At 19 to 20 years of age, these

Komsomol members have joined the ranks of the

leading scientific pathfinders . Komsomol scientists,

. ..

people with enormous concentration, purposefulness

and organization, they are blazing the trail into the

unknown on the basis of harmonious collective work."

We presented sunreys of current literature and

reported on the results of our own.. . research at

seminars. This was an arduous and difficult test, we

had to be prepared to answer the searching ..a nd

pointed questions of "Dau" (L. D. Landau) and

I. V. Qbreimov. At these seminars we put to test the

scientific data of?tained, and acquired the ability to

carry on a scientific dispute. All this made for a special

atmosphere of joint involvement in the solution of the

icurrent problems of modem physics, demanded an

9