Table Of ContentMany of the designations used by Inanufacturers and sellers to distinguish their

products are claill1.ed as tradelnarks. Where those designations appear in this book

and Perseus Books was aware of a tradelnark claill1, the designations have been

printed in initial capit~lletters.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

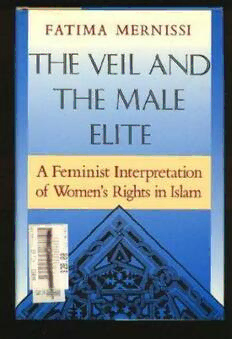

Mernissi, Fatin1.a.

[Harell1 politique. English]

The veil and the luale elite : a fenunist interpretation of wOlnen's rights in

Islaln /

Fatiu1.a Mernissi ; translated by Mary Jo Lakeland.

p. Cll1..

Translation of: Le harell1. politique.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-201-52321-3

ISBN 0-201-63221-7 (pbk.)

1. WOlnen in the Hadith. 2. WOlnen in Islan1.. 3. Muhalunud, Prophet.

d. 632-Views on WOlnen.

BP135.8.W67M4713 1991

297' . 12408-dc20 90-47404

elP

Copyright © Editions Albin Michel S.A. 1987

English translation © Perseus Books Publishing, L.L.C. 1991

All rights reserved. No part of this publication Inay be reproduced, stored in a re

trieval systeln, or transnutted, in any fornl or by any Ineans, electronic, ll1echan

ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written pennission

of the publisher. Printed in the United States of fullerica. Published Sil11ultane

ously in Canada.

Perseus Books is a l11elnber of the Perseus Books Group

Cover design by Marge Anderson

Set in 11/13-point Bel11bo by Hope Services (Abingdon) Ltd, Great Britain

8 9 10 11 03 02 01 00 99

Contents

Preface to the English Edition VI

Acknowledgments X

Map of Arabia at the Time of the Hejira XU

Introduction

1

PART I Sacred Text as Political Weapon

The Muslim and Time IS

I

2 The Prophet and Hadith 25

3 A Tradition of Misogyny (1)

49

4 A Tradition of Misogyny (2) 62

PART II Medina in Revolution: The Three Fateful Years

5 The Hijab, the Veil 85

6 The Prophet and Space 102

7 The Prophet and. Women

115

8 ~U mar and the Men of Medina 141

9 The Prophet as Military Leader 161

The Hijab Descends on Medina

10 180

Conclusion

Notes

APPENDICES

Appendix Sources

I 217

Appendix Chronology

2 223

Index

227

Preface to the English Edition

Is Islam opposed to women's rights? Let us take a look at the

international situation, to see who is really against wom.en.

Is it not odd that il1 this extraordinary decade, the 1990S, when

the whole world is swept by the irresistible chant for human

rights, sung by women and men, by children and grandparents,

from all kinds of religious backgrounds and beliefs, in every

language and dialect fron1 Beijing to the Americas, one finds only

one religion identified as a stun1bling block on the road to true

democracy? Islam alone is condemned by n1any Westerners as

blocking the way to women's rights. And yet, though neither

Christianity nor Judaism played an important role ill promoting

equality of the sexes, n1illions of Jewish and Chistial1 women

today enjoy a dual privilege - full hun1an rights on the one hand

and access to an inspirational religious tradition on the other. As

an Arab woman, particularly fascinated by the way people in the

modern world manage and integrate their past, I am constalltly

surprised when visiting Europe and the USA, who "sell" them

selves as super-modern societies, to find how Judeo-Christian

their cultural atmosphere really is. It may escape them, but to an

outsider Europe and the USA are particularly rich in religious

influences, in myths, tales, and traditions. So much so that I

continually find myself asking questions such as "What do you

mean by St George and the Dragon?" simply so that I can follow

conversations.

Westerners make unconscious religious references constantly in

VI

Preface to the Edition

En<~lish

their daily activities, their creative thillking, and their approach to

the world around them. When Neil Armstrong and his fellow

astrol1auts walked on the m0011 on July 20, I969, they read to the

millions watching them, including us Muslims, the first chapter of

the Book of Genesis: "In the Beginning God created the Heavens

and the Earth . . ." They did 110t sound so very modern. They

sounded to us very religious indeed, in spite of their spacesuits.

When I went to the USA in I986 I was surprised to see preachers

Christiall-style mullahs - recitillg day-long sermons on satellite

television! SOllle banks alld businesses evidently found it worth

their while to fillance whole days of religious transmissions,

poured free of charge into Anlerican homes. Here is a clear message

for those who doubt Islam's capacity to survive nlodernity, calling

it unfit to accompany the age of higher technology: why should

Islam fail where Judaism alld Christiallity so clearly succeed?

What can we women COllclude fronl the Euro-American

situatioll? First, we see religion call be used by all kinds of

organizations in the modern world to promote money-nlaking

projects; and second, since Islam is no more repressive than

Judaism or Christiallity, there must be those who have a vested

interest in blockillg women's rights in Muslim societies. The cause

must again be profit, and the question is: how and where can a

businessman who profitably exploits women (whether the head of

a multinational or a local bazaar entrepreneur), find a source in

which he can dip his spurious rationale to give it a glow of

authenticity? Surely not in the present. To defend the violation of

women's rights it is necessary to go back illtO the shadows of the

past. This is what those people, East or West, who would deny

Muslim women's claim to democracy are trying to do. They

camouflage their self-interest by proclaiming that we can have

either Islam or delllocracy, but never both together.

Let us leave the international scene and go into the dark back

streets of Medina. Why is it that we find some Muslim men saying

that women in Muslim states cannot be granted full enjoyment of

human rights? What grounds do they have for such a claim? None

- they are simply betting on our ignorance of the past, for their

argument can never convince anyone with all elementary under

standing of Islam's history. Any lllan who believes that a Muslim

..

VB

Preface to the En<.<?lish Edition

woman who fights for her dignity and right to citizellship

excludes herself necessarily from the umma and' is a brainwashed

victim of Western propaganda is a man who misunderstands his

own religious heritage, his own cultural identity. The vast and

inspiring records of Muslim history so brilliantly completed for us

by scholars such as Ibn Hisham, Ibn Hajar, Ibn Sa~ad, and Tabari,

speak to the contrary. We Muslim women can walk into the

modern world with pride, knowing that the quest for dignity,

democracy, and human rights, for full participation in the political

and social affairs of our country, stems from no inlported Western

values, but is a true part of the Muslim tradition. Of this I am

certain, after reading the works of those scholars mentioned above

and many others. They give me evidence to feel proud of my

Muslim past, and to feel justified in valuing the best gifts of

modern civilization: human rights and the satisfaction of full

ci tizenshi p.

Ample historical evidence portrays women in the Prophet's

Medina raising their heads from slavery and violence to claim their

right to join, as equal participallts, in the making of their Arab

history. Women fled aristocratic tribal Mecca by the thousands to

enter Medina, the Prophet's city in the severith century, because

Islam promised equality and dignity for all, for men and women,

masters and servants. Every woman who came to Medina when

the Prophet was the political leader of Muslims could gain access

to full citizenship, the status of sahabi, Companion of the Prophet.

Muslims can take pride that in their language they have the

feminine of that word, sahabiyat, women who enjoyed the right to

enter into the councils of the Muslim umma, to speak freely to its

Prophet-leader, to dispute with the men, to fight for their

happiness, and to be involved in the managemellt of nlilitary and

political affairs. The evidence is there in the works· of religious

history, in the biographical details of sahabiyat by the thousand

who built Muslim society side by side with their male counterparts.

This book is an attempt to recapture some of the wonderful and

beautiful moments in the first Muslim city in the world, Medina

of the year (the first year of the Muslim calendar), when

622

aristocratic young women and slaves alike were drawn to a new,

mysterious religion, feared by the masters of Mecca because its

V1l1

Preface to the E1'lJ~lish EditioH

prophet spoke of matters dangerous to the establishment, of

human dignity and equal rights. The religion was Islam and the

Prophet was Muhammad. Al1d that his egalitarian message today

sounds so foreign to many ill our Muslim societies that they claim

it to be imported is indeed one of the great enigmas of our times. It

is our duty as good Muslims to refresh their memories. Inna

nafa f!at al-dhikra (of use is the reminder) says the Koran. When I

finished writing this book I had co~e to understand one thing: if

women's rights are a problem for some modern Muslim men, it is

neither because of the Koran nor the Prophet, nor the Islamic

tradition, but simply because those rights conflict with the

interests of a male elite. The elite faction is trying to convince .us

that their egotistic, highly subjective, al1d mediocre view of

culture and society has a sacred basis. But if there is one thil1g that

the women and men of the late twentieth century who have an

awareness and enjoyment of history can be sure of, it is that Islam

was not sent from heaven to foster egotism and mediocrity. It

came to sustain the people of the Arabian desert lands, to

encourage them to achieve higher spiritual goals and equality for

all, in spite of poverty al1d the daily cOl1flictbetween the weak and

the powerful. For those first Muslims democracy was nothing

unusual; it was their meat and drink and their wonderful dream,

waking or sleeping. I have tried to present that dream, and if you

should find pleasure in these pages it is because I have succeeded in

some small way, however inadequate, in recapturing the heady

quality of a great epoch.

IX

Acknowledgments

For sound advice regarding my research for this book I am

indebted to two of my colleagues at the Universite Mohammed V:

Alem Moulay Ahmed al-Khamlichi, and the philosopher fAli

Oumlil. The latter suggested to me the inclusion of the material

concerning the ordering of the suras in the Koran and the dating of

them; he also recommended to me some references concerning the

traditional methodology as regards the sacred texts. Alem Moulay

Ahmed al-Khamlichi gave me much advice and patiellt assistance,

rare amol1g colleagues, especially with chapters 2, 3, and 4,

concerning Hadith. His generosity even extended to putting his

own books at my disposal and marking the pages for me. I confess

that I would have hesitated to be so generous myself, because the

number of loaned books that you never see again has increased

sharply since the war in Lebanon, which has sent the price of

Arabic books soaring. Professor Khamlichi teaches Muslim law at

the Faculte de Droit of the Universite Mohammed V. In his

capacity as ~alim (religious scholar), he is also a member of the

council of fulama of the city of Rabat and a specialist in problems

dealing with women in Islam. It was he who gave me the idea for

this book. It was while listening to him at a televised conference at

the Rabat mosque, expounding his views on the initiative of the

believer with regard to religious texts, that I felt the necessity for a

new interpretation of those texts.

I am also grateful for the patience and unflagging aid of M.

Boufnani, director of the Institut Ibn-Ruchd of the Faculte de

x

A(knowle~,?tnetlts

Lettres of Rabat, who saved me much tin1e with regard to finding

and consulting the available documents in the library of the

Faculte de Lettres; to the Bibliotheque Gcncrale of Rabat; to

Mustapha Naji, bookseller, who turned the bookseller/client

relationship into an intellectual exchange and a debate on the

future of the Muslim heritage that was sometimes a little too

impassioned for my taste, but certainly fruitful; and to Madame

Dalili, who took care of all the concerns of daily life during the

I011g months of research and writing of this book.

Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to Claire

Delannoy, the first non-Muslim reader of this book, thanks to

whom the often problematic relationship between writer and

publisher became a veritable dialogue between cultures.

Xl

Adrianopl•e ~----BLACKSEA----~

Constantinople --------->.....

Siffin

.

MEDITERRANEAN EMPIRE

Damascus

~~-------------------------.-,---r"- ~~ . Busra OF

PERSIA

Jerusale ~

• "P

Gaza trl

Hira.

• Dumat aI-Jandal

Gulf of Aqaba

• Khaybar

• Medina

·Uhud

• Badr

• Hudaybiyya

YAMAMAT

•

Ta'if

ETHIOPIA

MAP OF ARABIA AT THE TIME OF THE HEJlRA