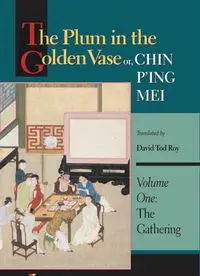

Table Of ContentTHE PLUM IN THE GOLDEN VASE

P R I N C E T O N L I B R A R Y OF A S I A N T R A N S L A T I O N S

The Plum in the Golden Vase

or,C H IN P’ING M EI

V O L U M E O N E :

T H E G A T H E R I N G

Translated by David Tod Roy

Copyright © 1993 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hsiao-hsiao-sheng.

[Chin P’ing Mei. English]

The plum in the golden vase, or, Chin P’ing Mei /

translated by David Tod Roy.

p.

cm. 一

(Princeton library of Asian translations)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: v. 1. The gathering.

ISBN 0-691-06932-8

ISBN 0-691-01614-3 (pbk.)

I. Roy, David Tod, 1933- .

II. Title.

III. Series.

PL2698.H73C4713

1993

895.Γ346—dc20

92-45054

CIP

The publication of this volume was made possible in part through

a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities,

an independent federal agency, to which we would like

to express our deep appreciation

This book has been composed in Bitstream Electra

Princeton University Press books are printed

on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for

permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity

of the Council on Library Resources

Printed in the United States of America ·

10

9

8

7

6

5

Excerpts reprinted from THE DIALOGIC IMAGINATION, by M. M. Bakhtin,

edited by Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist,

copyright ◎ 1981. By permission of the University of Texas Press.

To a ll those students,friends,and colleagues

W H O P A R T I C I P A T E D W I T H M E I N T H E E X C I T E M E N T

OF E X P L O R I N G T H E W O R L D OF T H E CHI N P I N G MEI

O V E R T H E PAST Q U A R T E R C E N T U R Y

CONTENTS

L i s t o f Il l u s t r a t io n s

xi

A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s

xiii

In t r o d u c t io n xvii

Ca s t o f C h a r a c t e r s

xlix

P re fa c e t o th e Ch i n P ’in g M e i

u -h u a

3

P re fa c e t o th e C h i n P ’in g M e i

6

C o lo p h o n

7

F o u r Ly r ic s t o t h e T u n e “B u r n in g In c e n s e ”

8

Ly r ic s o n t h e F o u r V ic e s t o t h e T u n e “Pa r t r id g e S k y”

10

CHAPTER 1

Wu Sung Fights a Tiger on Ching-yang Ridge;

P,an Chin-lien Disdains Her Mate and Plays the Coquette

12

CHAPTER 2

Beneath the Blind Hsi-men Ch’ing Meets Chin-lien;

Inspired by Greed Dame Wang Speaks of Romance

43

CHAPTER 3

Dame Wang Proposes a Ten-part Plan for “Garnering the Glow”

Hsi-men Ch’ing Flirts with Chin-lien in the Teahouse

62

CHAPTER 4

The Hussy Commits Adultery behind Wu the Elder’s Back;

Yün-ko in His Anger Raises a Rumpus in the Teashop

82

CHAPTER 5

Yün-ko Lends a Hand by Cursing Dame Wang;

The Hussy Administers Poison to Wu the Elder

96

CHAPTER 6

Hsi-men Ch’ing Suborns Ho the Ninth;

Dame Wang Fetches Wine and Encounters a Downpour

111

CHAPTER 7

Auntie Hsüeh Proposes a Match with Meng Yü-lou;

Aunt Yang Angrily Curses Chang the Fourth

125

vili

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 8

All Night Long P,an Chin-lien Yearns for Hsi-men Ch’ing;

During the Tablet-burning Monks Overhear Sounds of Venery

147

CHAPTER 9

Hsi-men Ch'ing Conspires to Marry P,an Chin-lien;

Captain Wu Mistakenly Assaults Li Wai-ch'uan

170

CHAPTER 10

Wu the Second Is Condemned to Exile in Meng-chou;

Hsi-men and His Harem Revel in the Hibiscus Pavilion

188

CHAPTER 11

P,an Chin-lien Instigates the Beating of Sun Hsüeh-o;

Hsi-men C h,in g Decides to Deflower Li Kuei-chieh

205

CHAPTER 12

P,an Chin-lien Suffers Ignominy for Adultery with a Servant;

Stargazer Liu Purveys Black Magic in Pursuit of Gain

224

CHAPTER 13

Li P,

ing-erh Makes a Secret Tryst over the Garden Wall;

The Maid Ying-ch'un Peeks through a Crack and Gets an Eyeful

253

CHAPTER 14

Hua Tzu-hsü Succumbs to Chagrin and Loses His Life;

Li P'ing-erh Invites Seduction and Attends a Party

274

CHAPTER 15

Beauties Enjoy the Sights in the Lantern-viewing Belvedere;

Hangers-on Abet Debauchery in the Verdant Spring Bordello

298

CHAPTER 16

Hsi-men Ch’ing Is Inspired by Greed to Contemplate Matrimony;

Ying Po-chüeh Steals a March in Anticipation of the Ceremony

316

CHAPTER 17

Censor Yü-wen Impeaches Commander Yang;

Li P'ing-erh Takes Chiang Chu-shan as Mate

337

CHAPTER 18

Lai-pao Takes Care of Things in the Eastern Capital;

Ch,en Ching-chi Supervises the Work in the Flower Garden

356

CHAPTER 19

Snake-in-the-grass Shakes Down Chiang Chu-shan;

Li P,

ing-e rh ,s Feelings Touch Hsi-men Ch’ing

376

C O N T E N T S

ix

CHAPTER 20

Meng Yii-lou High-mindedly Intercedes with Wu Yüeh-niang;

Hsi-men Ch’ing Wreaks Havoc in the Verdant Spring Bordello

401

APPENDIX I

Translator’s Commentary on the Prologue

429

APPENDIX II

Translations of Supplementary Material

437

N o t e s 449

Bib l io g r a p h y

543

In d e x

573

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

P’an Chin-lien Disdains Her Mate and Plays the Coquette

31

Beneath the Blind Hsi-men Ch’ing Meets Chin-lien

49

Dame Wang Proposes a Ten-part Plan for “Garnering the Glow”

63

Dame Wang Insists on the Proposed Remuneration for Her Plan

68

Hsi-men C h,in g Flirts with Chin-lien in the Teahouse

74

The Hussy Commits Adultery behind Wu the Elder’s Back

84

Yün-ko in His Anger Raises a Rumpus in the Teashop

94

Yün-ko Lends a Hand by Cursing Dame Wang

101

The Hussy Administers Poison to Wu the Elder

108

Hsi-men Ch’ing Suborns Ho the Ninth

113

Dame Wang Fetches Wine and Encounters a Downpour

121

Auntie Hsüeh Proposes a Match with Meng Yii-lou

135

Aunt Yang Angrily Curses Chang the Fourth

145

All Night Long P,an Chin-lien Yearns for Hsi-men C h,ing

149

During the Tablet-burning Monks Overhear Sounds of Venery

168

Hsi-men Gh,ing Conspires to Marry P,an Chin-lien

172

Captain Wu Mistakenly Assaults Li Wai-ch’uan

186

Wu the Second Is Condemned to Exile in Meng-chou

195

Hsi-men and His Harem Revel in the Hibiscus Pavilion

198

Hsi-men C h,ing and His Cronies Form the Brotherhood of Ten

202

P,an Chin-lien Instigates the Beating of Sun Hsüeh-o

212

Hsi-men Ch’ing Decides to Deflower Li Kuei-chieh

221

P,an Chin-lien Suffers Ignominy for Adultery with a Servant

238

Stargazer Liu Purveys Black Magic in Pursuit of Gain

250

Li P’ing-erh Makes a Secret Tryst over the Garden Wall

263

The Maid Ying-ch'un Peeks through a Crack and Gets an Eyeful

265

Hua Tzu-hsü Succumbs to Chagrin and Loses His Life

286

Li P'ing-erh Invites Seduction and Attends a Party

288

Beauties Enjoy the Sights in the Lantern-viewing Belvedere

305

Hangers-on Abet Debauchery in the Verdant Spring Bordello

313

Hsi-men Gh,ing Is Inspired by Greed to Contemplate Matrimony

318

Ying Po-chüeh Steals a March in Anticipation of the Ceremony

334

Censor Yü-wen Impeaches Commander Yang

342

Li P,

ing-erh Takes Chiang Chu-shan as Mate

354

Lai-pao Takes Care of Things in the Eastern Capital

361

On Seeing P’an Chin-lien Ch’en Ching-chi Loses His Wits

369

Snake-in-the-grass Shakes Down Chiang Chu-shan

389

Eavesdroppers Discuss Li P,

ing-erh,s Feat of Reconciliation

405

Hsi-men Ch,

in g ,s Cronies Make a Fuss over His New Bride

416

Hsi-men Ch’ing Wreaks Havoc in the Verdant Spring Bordello

425

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T o MY PARENTS, Andrew Tod Roy and Margaret Crutchfield Roy, who

served as Presbyterian missionaries in China and Hong Kong from 1930 to

1972,I owe my initial exposure to Chinese language and culture and my

interest in Chinese literature.

It was not until the summer of 1949 when I was a sixteen-year-old school

boy in Nanking that I began,at the insistence of my mother, the serious

study of the Chinese language, together with my younger brother, James

Stapleton Roy, who is now United States ambassador to China.

During the following decade I was fortunate to be able to study Chinese

poetry with Frederick W Mote;

literary Chinese and Sinological method

with Derk Bodde,Yang Lien-sheng, and Francis Woodman Cleaves;

Chi

nese history with John King Fairbank; Chinese thought with Benjamin

Schwartz; and Chinese literature with James Robert Hightower and David

Hawke s. I was also lucky to have Harold L. Kahn and Lloyd Eastman as

roommates; and Li-li Ch’en,Elling Eide, Philip A. Kuhn, and Nathan Sivin

as fellow students. No one could have had a more distinguished roster of

mentors or more stimulating and congenial classmates.

I first encountered Clement Egerton’s translation of the Chin P’ing Mei

in the library of the University of Nanking in 1949,and it was in the spring

of 1950, not long before the outbreak of the Korean War, that I bought my

first copy of the Chin P’ing Mei tzu-hua in Fu-tzu Miao, an area full of

secondhand bookstores and curio shops adjacent to the Confucian Temple

in Nanking. W hile serving a two-year hitch in the Army Security Agency

between 1954 and 1956,I bought my first copy of Chang Chu-p,

o,s edition

of the Chin P,ing Mei on January 20,1955,in the bookstore of the Confu

cian Temple in Tokyo. In view of the Confucian interpretation of the Chin

P’ing Mei that I was to develop several decades later, it is a Nabokovian

coincidence that the first two copies of the book that I acquired were pur

chased in the purlieus of Confucian Temples.

Over the years, as I read and reread the novel,and especially after I started

to teach it at the University of Chicago in 1967,I began to think I saw things

in it that had not been pointed out before,but I could not have contributed

anything to the study of this tantalizingly enigmatic work if I had not been

able to stand on the shoulders of such giants as the seventeenth-century

critic Chang Chu-p'o (1670-98), and the twentieth-century scholars Wu

Han, Yao Ling-hsi,Feng Yüan-chün,and Patrick Hanan, to name only the

most important of them. Their work has not only provided an indispensable

foundation but has been a constant source of inspiration to me. Like all

students of Chinese fiction and drama, I have also benefited greatly from

xiv

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S

the pioneering publications of Cheng Chen-to,Sun K’ai-ti,Wu Hsiao-ling,

James Crump, Cyril Birch, Hsii Shuo-fang, and C. T. Hsia.

My most consistent source of stimulation over the years, however, has

been the work of such former students and present colleagues as Andrew H.

Plaks, Daniel Overmyer,Paul V Martinson, Martha Howard, Peter Li, Jean

Mulligan, Katherine Carlitz, Gail King, Sally Church, David Rolston,Indira

Satyendra, Amy McNair, Dale Hoiberg,Janet Lynn, and Charles Stone.

Successive curators of the East Asian Library at the University of Chicago,

including T. H. Tsien,James Cheng, and Ma Tai-loi, himself a major con

tributor to scholarship on the Chin P’ing Meif have provided invaluable help

in keeping me abreast of the flow of current publications on this subject, a

trickle that has recently turned into a flood.

Of those who have read all or part of the manuscript before publication

and whose suggestions have helped to improve it in innumerable ways, I

wish particularly to thank my friend and former colleague Lois Fusek,the

first person to whom I showed the fruits of my labors as I proceeded, and to

whose sensitive ear for stylistic niceties I owe the avoidance of many a blun

der as well as the gift of many a felicitous emendation. Andrew H. Plaks,

David Rolston, and my cousin Catherine Swatek have all read the transla

tion from beginning to end together with the Chinese text and have been

generous enough to share with me their detailed and invaluable critical re

actions. Others who have read parts of the manuscript and offered sugges

tions for its improvement include Steven Black, Katherine Carlitz, Susan

Daruvala, John C. Duggan, Magnus Fiskesjö, Harold L. Kahn, Matthew

Krasowski,Robert A. LaFleur, Lin Chi-ch’eng,Lin Hsiu-ling; Amy Mayer,

Robert H. Mazur, Andrea Paradis, Kenneth W. Phifer, Michael J. Puett,

Alane Rollings, James St. André, Indira Satyendra, Edward Shaughnessy,

Nathan Sivin, Laura Skosey,Charles Stone, Janelle Taylor, and Natalie

Wainright.

To my wife, Barbara Chew Roy, who urged me to embark on this intermi

nable task, and who has lent me her unwavering support over the years

despite the extent to which this work has preoccupied me, I owe a particular

debt of gratitude. W ithout her encouragement I would have had neither the

temerity to undertake the task nor the stamina to continue it.

For indispensable technical advice and assistance concerning computers,

printers, and word-processing programs I would like to thank René Pomer-

leau,my brother James Stapleton Roy, my colleague Ts’ai Fang-p,

ei,and

particularly Charles Stone.

The research that helped to make this work possible was materially as

sisted by a Grant for Research on Chinese Civilization from the American

Council of Learned Societies in 1976-77. The first draft of the translation

itself was supported by a grant from the Translation Program of the Na

tional Endowment for the Humanties in 1983-86. The Department of East