Table Of ContentYOUNG CENTER BOOKS IN ANABAPTIST PIETIST STUDIES

DONALD B. Kraybill, Series Editor

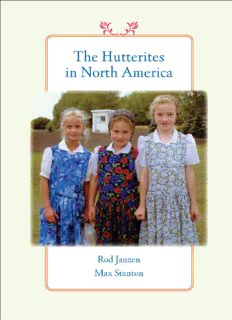

Two Hutterite sisters near a pond in Alberta.

The Hutterites in North America

Rod Janzen

Max Stanton

© 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2010

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Janzen, Rod A.

The Hutterites in North America / Rod Janzen and Max Stanton.

p. cm. — (Young Center books in Anabaptist and Pietist studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-80189489-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8018-9489-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Hutterite Brethren—North America. 2. North America—Church history. I.

Stanton,

Max Edward, 1941– II. Title.

BX8129.H8J35 2010

289.7′3—dc22 2009033024

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Frontispiece: Courtesy of Max Stanton.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more

information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or

[email protected].

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book

materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent

post-consumer waste, whenever possible. All of our book papers are acid-free,

and our jackets and covers are printed on paper with recycled content.

Mammon is nothing else but what is temporal; and that which is another’s

is that which is borrowed, with which a man plays for a while like a cat with

the mouse. And afterwards he must leave it to somebody else,

and in the end his folly becomes evident.

—Hutterite sermon on Acts 2

Contents

List of Figures, Tables, and Maps

Preface

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER 1. Communal Christians in North America

CHAPTER 2. Origins and History

CHAPTER 3. Immigration and Settlement in North America

CHAPTER 4. Four Hutterite Branches

CHAPTER 5. Beliefs and Practices

CHAPTER 6. Life Patterns and Rites of Passage

CHAPTER 7. Identity, Tradition, and Folk Beliefs

CHAPTER 8. Education and Cultural Continuity

CHAPTER 9. Colony Structure, Governance, and Economics

CHAPTER 10. Population, Demography, and Defection

CHAPTER 11. Managing Technology and Social Change

CHAPTER 12. Relationships with Non-Hutterites

CHAPTER 13. Facing the Future

Appendix: Hutterite Colonies in North America, 2009

Glossary

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Figures, Tables, and Maps

FIGURES

10.1. Birthrate by Hutterite Leut 10.2. Hutterite mothers’ age at last birth TABLES

2.1. Hutterites in Europe and North America 2.2. Hutterites in Europe 4.1. The

Hutterite-Bruderhof relationship 4.2. Hutterite colonies 5.1. Schmiedeleut

ministers’ previous colony positions 7.1. Surnames and ethnic backgrounds 7.2.

Surname distribution in four colonies 9.1. Colony leadership structure 10.1.

Hutterite birthrates 10.2. Hutterite surnames in public telephone directories MAPS

Hutterite colonies, 2009

Hutterite settlements in Europe, 1528–1879

Dariusleut and Lehrerleut colonies, 2009

Schmiedeleut colonies, 2009

Preface

God does not want his children here on earth to live like cattle, donkeys

and oxen, which are only out to fill their bellies for themselves, without

concern for others.

—Hutterite sermon on Luke 3, circa 1650

At the Wilson Siding Hutterite Colony in southern Alberta, German teacher

Henry Wurz walks quickly across the yard late on a Thursday afternoon. He has

been working in the garden. Sporting a reddish beard and very dusty pants,

Henry says hello and invites us into his home, one of the colony’s many large

single-family residences, with five or six bedrooms and a full basement. Inside

the house, Henry glances at the clock, sees that it is almost time for evening

church, and quickly changes into plain black dress. Henry’s daughters gather in

the kitchen, waiting for a sign to begin walking to the church building. The

youngest girls wear head coverings and simple long dresses, but they are also

barefoot. This is a very hot day.

At the church service, minister Joe Wurz greets members of the congregation.

Then he names a hymn and chants the first line. In response about seventy

people sing out loudly and passionately, and one can see that they are being

transported into a different realm of reality. The hymn is long, with many verses

and lines, and there is no holding back as males and females sing at the top of

their lungs in a minor key. All of them, adults and children, sing without

hymnbooks, following memorized tunes, often slurring notes, and emitting one

of the most ear-shattering and otherworldly sounds that one will ever hear. The

hymn is followed by a short sermon, read from a collection of sacred writings

that are hundreds of years old. The meeting closes with prayer. With heads

bowed, all kneel reverently on the hard linoleum floor.

This is Hutterite life on any late afternoon. From south-central South Dakota

to northwestern Alberta, this is what Hutterite men and women do at the end of a

day of hard physical labor. A twenty-minute church service (the Gebet) precedes

the evening meal, giving Hutterite men and women an opportunity to reflect on

their lives, to worship God, and to regroup intellectually and spiritually. The late-

afternoon Gebet ensures that, whatever has happened during the day, there is

always a time set aside when members of the community come together to focus

on the meaning and purpose of their lives.

Today nearly five hundred Hutterite communities, or colonies, are scattered

across the northern plains states of the United States and the prairie provinces of

Canada. Since the sixteenth century, the Hutterites have lived communally,

sharing all of their material resources and maintaining as much isolation from

the rest of the world as possible. Having outlasted most other communal

societies, they provide a striking social and economic contrast and alternative to

the individualistic way of life that is commonplace in industrialized Western

countries in the postmodern world.

Hutterites are Old Order Christians who dress simply and maintain religious

and cultural traditions that are hundreds of years old. They speak a distinctive

German dialect, live in isolated rural areas, and manage change with careful

discernment and unapologetic discrimination. Hutterites honor the earth and

interact with the natural world as careful stewards of God. Uniquely adept at

interpersonal relations and conflict resolution, they use democratic procedures to

make the important decisions that affect their lives.

In this book we introduce a group of Old Order Christians who exude

confidence as well as humility. Hutterites refuse to be assimilated into the social

mainstream of the United States and Canada, and they do not vote or serve in the

military. They dress like nineteenth-century eastern European villagers and for

the most part keep to themselves. Yet Hutterites are some of the most hospitable,

generous people one will ever meet. They are also remarkably knowledgeable

about contemporary social, economic, and political developments. The

Hutterites also continue to increase in numbers, with high birth and retention

rates. In the 1870s, when they arrived in the Dakota Territory, 425 Hutterites

lived in three small communities. Today the Hutterite population exceeds

49,000.

Since the last major work on the Hutterites, John Hostetler’s Hutterite

Society, was published in 1974, many important changes have occurred. Our

book weaves research findings of the past thirty-five years together with our own

analysis of Hutterite beliefs and practices.1 Our descriptions and assessments are

based on twenty-five years of interaction with Hutterites at colonies in every

state and province where they have established communities. We review all

aspects of Hutterite life and view it from a variety of vantage points, discussing

negative and positive developments and describing how Hutterite communities

Description:One of the longest-lived communal societies in North America, the Hutterites have developed multifaceted communitarian perspectives on everything from conflict resolution and decision-making practices to standards of living and care for the elderly. This compellingly written book offers a glimpse in