Table Of ContentTHE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO 60637

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, LTD., LONDON

© 1992 by The University of Chicago.

All rights reserved. Published 1992.

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 11 12 13 14

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-72812-4 (paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-72812-9 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-02749-4 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rosenthal, Margaret F.

The honest courtesan : Veronica Franco, citizen and writer in

sixteenth-century Venice / Margaret F. Rosenthal.

p. cm. — (Women in culture and society)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-226-72812-9 (pbk.)

1. Franco, Veronica, 1546–1591. 2. Venice (Italy)—Intellectual life.

3. Courtesans—Italy—Biography. 4. Authors, Italian—16th century—

Biography. I. Title. II. Series.

DC678.24.F73R67 1992

945′.3107’092—dc20 92-14540

[B] CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum

requirements of the American National Standard for Information

Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI

Z39.48-1992.

THE HONEST

COURTESAN

VERONICA FRANCO

CITIZEN AND WRITER IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY

VENICE

Margaret F. Rosenthal

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago & London

W C S

OMEN IN ULTURE AND OCIETY

A Series Edited by Catharine R. Stimpson

Contents

F by Catharine R. Stimpson

OREWORD

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I

NTRODUCTION

1. S C F E

ATIRIZING THE OURTESAN: RANCO’S NEMIES

2. F H C F

ASHIONING THE ONEST OURTESAN: RANCO’S

P

ATRONS

Appendix: Two Testaments and a Tax Report

3. A V F F L

DDRESSING ENICE: RANCO’S AMILIAR ETTERS

4. D C F I

ENOUNCING THE OURTESAN: RANCO’S NQUISITION

T P D

RIAL AND OETIC EBATE

Appendix: Documents of the Inquisition

5. T C E A E F

HE OURTESAN IN XILE: N LEGIAC UTURE

N

OTES

W C

ORKS ITED

I

NDEX

I

LLUSTRATIONS

Foreword

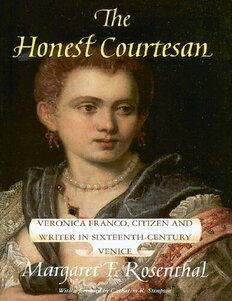

An extraordinary woman, Veronica Franco was born

in 1546 in Venice. Because they were citizens of

Venice by birth, members of her family had a secure

legal identity. They were, however, neither rich nor

powerful. Indeed, Franco’s mother was a penurious

courtesan. Following a tradition among economically

vulnerable Venetian mothers and daughters, Franco,

too, became a courtesan. She made a success of

her profession: visiting Venice, a future king of

France called on her. Veronica was also a brilliant

woman whose gifts compelled her to develop them.

She educated herself and then invented herself as a

literary figure. Here, too, she succeeded. Between

1570 and 1580, she wrote poetry and public letters.

She took on editorial projects. Tintoretto, the

Venetian painter, did her portrait. Regrettably, when

she died in 1591, much of the wealth she had earned

was gone, a lot of it apparently stolen. Yet, Franco’s

life, on balance, was a dramatic narrative of the

exercise of will and talent.

Now Tita Rosenthal has written The Honest

Courtesan, the first major study of Veronica Franco in

English. Massive and meticulous, the result of both

scrupulous archival research and elegant textual

readings, The Honest Courtesan places Franco in

the culture and society of Venice, the native city that

she left perhaps twice, once to embark upon a

pilgrimage to Rome, once to go into exile because of

a shattered relationship. Within Venice, alluring,

exciting, and beautiful though it was, Franco had to

manage—with skill, imagination, and energy—her

own life, children and family, and profound cultural

tensions concerning sex and gender.

In brief, although female figures dominated the

city’s public iconography, few women could actually

enter into the city’s public discourse. Fortunately for

Franco, Venice, the center of European publishing,

provided as many opportunities for writers of both

genders as any city might have. Moreover, Venetian

iconography adapted and burnished a common

Western polarity in the representation of women, the

polarity between angel and witch, virgin and whore,

Virgin Mary and Eve, or, in Venice’s self-presentation,

between an immaculate, pure, virtuous city and a

luxury loving, bejewelled, voluptuous one. In part to

ensure the purity of its women, especially the wives

and daughters of the elite, Venice regulated them

strenuously. Their space was to be private, not

public. Because “good women” were so restricted,

“bad women” had this social role of playmate and

source of sexual release. As Rosenthal notes, the

Venetian courtesan, like the Japanese geisha, was

expected to provide cultivated company and good

conversation as well. However, during periods of

grave social and economic danger, such as mid-

1570s when the plague infected Venice, the

courtesan and prostitute were conveniently available

as symbols of disorder and vileness.

Franco had her patrons and supporters, especially

Domenico Venier, who conduted an influential salon.

She could not have survived without them. However,

she also seems to have been very much her own

woman, the author of her own self-promotions and

self-justifications. She had two, inseparable tasks: to

defend the courtesan and to take on a public role

forbidden to the conventional woman. The voice that

she created was that of “honest courtesan and

citizen poet” (MS 108). In careful detail, Rosenthal

shows the twists, turns, and rhetorical strategies of

this voice; its parallels to and divergences from that

of the male courtier; and, significantly, its reworking

of the genres and motifs of classical and

Renaissance literature in order to permit a woman’s

voice to flourish. For, Franco—talking with men,

working with men, sleeping with men, giving birth to

three surviving sons—forgot neither women nor the

realities of prostitution. Indeed, two wills leave money

for poor women.

If powerful men helped Franco to survive, powerful

men also opposed and abused her. Some were

fellow writers, among the most vicious a relative of

her patron, Domenico Venier. They projected their

own social, professional, and psychological anxieties

onto women in general, the figure of the

courtesan/prostitute in particular, and, most

particularly, onto Franco herself. Then, in 1580, the

courts of the Inquisition summoned her on charges of

performing heretical incantations, charges that the

male tutor of her children had first filed. The

language of her self-defense when she was on trial

was similar to that of her self-defense against poets

when they attacked her. Once again, she won out,

though at an unquantifiable cost. After the trial, the

charges against her were dropped.

In one of the poems in which Franco confronts a

male poet who is her adversary, she pictures herself

as an Amazon warrior, an image that women writers

have frequently used. She is leading her tribe into

battle. She writes, “When we too are armed and

trained, we can convince men that we have hands,

feet and a heart like yours; and although we may be

delicate and soft, some men who are delicate are

also strong. . . . Women have not yet realized this, for

if they should decide to do so, they would be able to

fight you until death; and to prove that I speak the

truth, amongst so many women, I will be the first to

act, setting an example for them to follow; and on

you who have sinned against them all, I turn with

whichever weapon you may choose, with the wish

and hope of throwing you to the ground” (MS 351).

Strong, clever, bold, cunning, Veronica Franco

refused to be exiled from language and literature.

Because of The Honest Courtesan, we now realize

how grateful we must be for this strength, cleverness,

boldness, and bountiful refusal.

Catharine R. Stimpson

Rutgers University