Table Of ContentThis content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:20 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Haitians

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:20 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A book in the series Latin Amer i ca in Translation / en Traducción / em Tradução

This book was sponsored by the Consortium in Latin American and Car ib bean Studies

at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University.

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:20 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Haitians

A Decolonial History

Jean Casimir

Translated by Laurent Dubois

With a Foreword by Walter D. Mignolo

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:20 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Translation of the books in the series Latin Amer i ca in Translation /

en Traducción / em Tradução, a collaboration between the Consortium in

Latin American and Ca rib bean Studies at the University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill and Duke University and the university presses of the

University of North Carolina and Duke, is supported by a grant from the

Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

© 2020 The University of North Carolina Press

Foreword © 2020 Walter D. Mignolo

All rights reserved

Set in Adobe Text Pro by Westchester Publishing Ser vices

Manufactured in the United States of Amer i ca

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the

Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data

Names: Casimir, Jean, author. | Dubois, Laurent, 1971– translator. |

Mignolo, Walter, writer of foreword.

Title: The Haitians : a decolonial history / Jean Casimir ; translated by

Laurent Dubois ; with a foreword by Walter D. Mignolo.

Other titles: Latin Amer i ca in translation/en traducción/em tradução.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2020. |

Series: Latin Amer i ca in translation/en traducción/em tradução |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020022322 | ISBN 9781469651545 (cloth : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9781469660486 (paperback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469660493 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Sovereignty. | Haiti— Politics and government. |

Haiti— History. | Haiti— Colonization— History.

Classification: LCC F1921 .C267 2020 | DDC 972.94— dc23

LC rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020022322

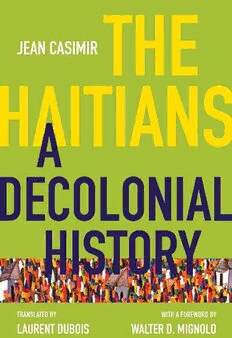

Cover illustration: Laurent Casimir (Haitian, 1928–1990), Crowded Market

(1972, oil on Masonite, 36" x 48"), Milwaukee Art Museum, gift of Richard and

Erna Flagg, M1991.117. Photograph by Larry Sanders, used by permission of the

Milwaukee Art Museum.

Photographer credit: Larry Sanders

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:20 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contents

Foreword, vii

Thinking Decoloniality beyond One Nation– One State

Preface and Acknowl edgments, xvii

Translator’s Note, xxv

Chapter 1 Introduction, 1

Perspective

Chapter 2 Resisting the Production of Sufferers, 26

Chapter 3 Colonial Thought, 69

Chapter 4 Slaves or Peasants, 101

Chapter 5 The Pursuit of Impossible Segregation, 134

Chapter 6 The Citizen Property Owner, 187

Chapter 7 Public Order and Communal Order, 221

Chapter 8 The Power and Beauty of the Sovereign People, 264

Chapter 9 An In de pen dent State without a Sovereign People, 306

Chapter 10 The State in the Nineteenth Century, 352

Notes, 395

Bibliography, 403

Index, 415

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

This page intentionally left blank

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Foreword

Thinking Decoloniality beyond One Nation– One State

Walter D. Mignolo

I

In her celebrated TED talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” Chimamanda

Ngozi Adichie makes a power ful po liti cal statement, a politics that no doubt

touches the core of the well- crafted discourses of scholarship, journalism,

state, banks, and corporations. She asserts that individuals’ single stories are

dangerous not only because the storyteller ( whether scholar, journalist,

banker, or officer of the state) acts on the assumption of the truth, without

any parentheses, of what the story conveys (what the storyteller “says”), but

also b ecause the storyteller assumes that t here is only one place to start the

story.

Adichie captured this second aspect of storytelling ( whether scientific,

scholarly, journalistic, literary, po liti cal, economic) when she underscored

that stories truly depend on where you start. She gave a c ouple of examples,

and I w ill paraphrase one: if you start from asserting the failure of state build-

ing in Africa, you may very well end up justifying colonialism. If you start

from the fact that state building in Africa truly comprised a colony of Eu ro-

pean imperialisms (a map of Africa in 1900, a de cade and a half a fter the Ber-

lin Conference, reveals that there is not one single corner of the continent

that was not u nder the control and management of Eu ro pean countries), then

you may very well end up apprehending and understanding the lies that jus-

tified and continue to justify colonialism. That is, you may very well end up

disparaging and critiquing the lies of modernity (such as conversion to Chris-

tian ity, pro gress, the “civilizing mission,” and development).

This is precisely what Jean Casimir’s argument in this book, as well as in

his previous publications, intends to do: to expose the limits (and the dan-

gers sometimes) of extant stories and interpretations of Hispaniola, Saint

Domingue, and fi nally Haiti (three diff er ent names that erased, from the early

arrival of Spanish ships, the name that the Tainos had for their territory—

Ayiti). The analytic story that Casimir offers to us as “la merveilleuse inven-

tion of Haiti” is precisely that: the renaming and territorial reconfiguration

of a trajectory that started with the Spanish genocides of the Taínos; followed

by the French appropriation of a sector of the islands the Spaniards called

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hispaniola and the French called Saint-D omingue; and a fter 1804 ( after a

revolution that lasted from 1791 to 1804), the revolutionaries’ adoption of the

name Haiti to honor the memories of the indigenous inhabitants of the island,

before indigenous p eople from Eu rope invaded and exterminated them.

The question is who are the Haitian revolutionaries, what shall we under-

stand by the term Haitian Revolution? The answer to this question would de-

pend on where you start from. Would you start from the well- known heroes

of the revolution Jean- Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint Louverture, and Henry

Christophe, who confronted France’s management of the island but without

questioning the nation- state form that they wanted to create, or from the first

president of Haiti, a fter the assassination of Dessalines, Alexandre Pétion and

his conciliatory politics with the French government? Well, it so happened

that Casimir starts from neither of those points: he starts from the “power

and beauty of the sovereign p eople.” Beyond the official stories we are used to

and which are identified by proper names (the proper names I mentioned),

there are the silences of the past—in the happy formulation of Michel- Rolph

Trouillot, la beaute du peuple souverain. Here precisely is where Casimir

starts:

If readers ask what I have learned from writing this book that I now offer

to them, my answer is that above all, in how I live my personal life, I no

longer see my ancestors as former slaves. I d on’t even think of them as a

dominated class. Their misery is only the most superficial aspect of their

real ity. It is the real ity that colonialists prefer to emphasize, along with

those among them who oppose the cruelty of some colonists but don’t

ultimately reject colonization itself. Having finished this book, I have

come to realize that my ancestors, as individuals and as a group, never

stopped resisting slavery and domination. I am the child of a collective

of fighters, not of the vanquished. I have chosen to venerate them, to

honor t hese captives reduced to slavery, and those emancipated in thanks

for their military ser vice to colonialism. I do so despite their errors and

their occasional failures. (chapter 1; emphasis added)

The statement is crucial to understand Casimir’s argument both in what

he says and in his saying, in what he enunciates and in the enunciations he

builds, which I emphasized in italics in the previous sentences. The statement

is crucial also because Casimir plays the game of scholarship (his archive is

solid, his so cio log i cal training and practices of historiographical sociology

through the years has been impeccable) but at the same time, he disobeys it.

And herein is the force of his argument: the moment that he uses scholarship

to advance the cause of the “sovereign people” instead of using the “sover-

eign p eople” to advance scholarship. Casimir, as is clear in the statement and

viii Foreword

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

through the argument, let himself be guided by his emotions (“I am the child

of a collective of fighters, not of the vanquished”) exposed in his reasoning.

It depends on where you start from: if you start from the heroes and main-

tain the silence of the “sovereign p eople,” you remain within the colonial poli-

tics of knowledge. If you shift the geography of reasoning and let it be guided

by your emotions, you engage in the growing pro cesses nowadays of decolo-

nial politics of knowing, sensing, and believing.

II

“C aptives reduced to slavery”— another crucial distinction that reinforces

Casimir’s putting up from his locus enunciationi, which is normatively silenced

in any of the existing disciplines: disciplines promote objectivity and direct

your attention to the said while veiling the act of saying. Consequently,

Casimir proposes “a decolonial reading” of the invention, formation, and

transformation of “the Haitian p eople” since 1804, but one grounded in the

experiences and shared memories, mainly orally transmitted (no archives for

historians h ere), of the daily praxis of living in re- existence, building the com-

munal in spite of state politics, in any of their variety from 1804 to today.

How could “the p eople” have gained and maintained its sovereignty? Two dis-

tinctive praxes of living emerge from Casimir’s argument. One is explicit

and explained in detail in chapter 7: the question of language. While French

language remained the official language of the state of Haiti, Creole remained

the language of the “sovereign p eople.” Throughout the period of the French

monarchic state before 1789 as well as the succeeding bourgeois French suc-

cessions of republics and empires, “the sovereign p eople,” though captive and

physically enslaved, never surrendered and therefore w ere never captive or

enslaved in the sphere of language.

As Casimir states, “All be hav ior implies knowledge” (chapter 8). What we,

all of us human beings, know is the outcome not so much of what we see or

read, but of what we do (by will or force) and share in storytelling and con-

versations from the moment we come into this world, in what ever region and

moment one is born. For t hose who w ere born in Africa, in any of the exist-

ing kingdoms, languages, and systems of belief (religions), and w ere captured,

transported, and enslaved in New World plantations, their d oing was marked

by the experience of being hunted, of being transported, and being enslaved.

For their descendants, it was the experience in the New World as captive and

enslaved, u ntil the revolution started in 1791 at Bwa Kayiman. All of that built

a memory alien to French schooling before the revolution and French- style

schooling after the revolution: French language and Chris tian ity remained

alien to “the sovereign p eople” for whom the Creole language and Vodou spir-

ituality became the glue of the communal re- existence.

Thinking Decoloniality beyond One Nation– One State ix

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 19:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms