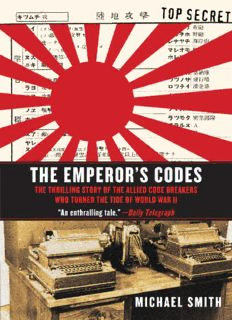

Table Of ContentTHE

EMPEROR’S

CODES

THE

EMPEROR’S

CODES

THE THRILLING STORY OF THE ALLIED

CODE BREAKERS WHO TURNED

THE TIDE OF WORLD WAR II

MICHAEL SMITH

Copyright © 2000, 2011 by Michael Smith All Rights Reserved. No part of

this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent

of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or

articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th

Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for

sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special

editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special

Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New

York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Arcade Publishing® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing,

Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smith, Michael, 1952

May 1-The emperor’s codes: the breaking of Japan’s secret ciphers / Michael

Smith.

p. cm.

Original edition has subtitle: Bletchley Park and the breaking of Japan’s

secret ciphers. Originally published: London : Bantam Press, 2000.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61145-017-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. World War, 1939-1945--

Cryptography. 2. World War, 1939-1945--Electronic intelligence. 3. Great

Britain. Government Communications Headquarters--History. 4. Machine

ciphers. 5. Cryptography--Japan. 6. Cryptography--United States. 7.

Cryptography--Great Britain. 8. ULTRA (Intelligence system) I. Title.

D810.C88S656 2011

940.54’8641--dc22

2011001771

Printed in the United States of America

For Ben, Kirsty, Louise, Leila and Levin

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am extremely grateful to all those former codebreakers and wireless

operators who wrote to me or agreed to be interviewed for this project. Whether

or not they are quoted in the book, their contributions played a major part in

providing the information and encouragement I needed to complete it. I am

particularly grateful to a number of people who went out of their way to help and

encourage me. These include Geoff Ballard; Edith Becker; Geoff Day; Joan

Dinwoodie; Joe and Barbara Eachus; Robert Hanyok; Margaret Henderson; Phil

Jacobsen; Dennis Moore; Joe Richard; Harry G. Rosenbluh; Hugh Skillen; Joe

Straczek; Jimmy Thirsk and Dennis Underwood. I am also grateful to Steve

Kelley for sharing his expertise in Japanese machine ciphers with me and to

Hilary Jarvis for her advice on the Japanese language. Special thanks are due to

Hugh Melinsky; Norman Scott; Alan Stripp and Maurice Wiles for allowing me

to quote from their own works and for their generous help and advice. I must

also thank Ron Bonighton, Director of Australia’s Defence Signals Directorate,

for kindly sending me a complete set of the Technical Records of the Central

Bureau (a uniquely generous example of openness from a signals intelligence

organization); Margaret Nave and the Australian War Memorial for allowing me

to quote from Eric Nave’s original manuscript; the Library and Department of

East Asian Studies of the University of Sheffield for permission to quote from

the diaries of Malcolm Kennedy; Christine Large and the staff of the Bletchley

Park Trust for their assistance and dedication to keeping the memory of the

codebreakers alive; and last but certainly not least Ralph Erskine whose

willingness to share his unrivalled knowledge of wartime codebreaking

operations with me provided a constant lifeline.

I should also like to thank Charles Moore, Editor of the Daily Telegraph,

for generously allowing me to take a sabbatical to write The Emperor’s Codes;

Sally Gaminara, Katrina Whone, Simon Thorogood and Sheila Lee at

Transworld for their painstakingly professional work on this project; my agent

Robert Kirby for his constant enthusiasm; and my wife Hayley for her patience

and encouragement. The Emperor’s Codes

‘I believe most experienced cryptanalysts would agree with me that

cryptanalysis is much closer to art than to science, and this is what makes the

personal factor so important.’

John Tiltman, Chief Cryptographer at Bletchley Park 1940–5

INTRODUCTION

The extraordinary achievements of the British codebreakers based at

Bletchley Park in cracking Nazi Germany’s ‘unbreakable’ Enigma cipher are

now widely known. This initially oddball collection of mathematicians,

classicists and musicians performed unexpected miracles in the hastily

constructed huts scattered around the grounds of an ugly mock-Tudor mansion

in the small Buckinghamshire market town of Bletchley. The location had been

selected in part because it was just far enough outside London to escape the

threat of German bombs. But perhaps more importantly, it was midway between

the ‘glittering spires’ of Oxford and Cambridge, from where most of the leading

codebreakers had come.

The apparently amateurish nature of these early beginnings was epitomized

by the actions of the codebreakers’ boss, Admiral Hugh Sinclair. His power over

the Government Code and Cipher School, as the codebreaking operation was

known, came from his role as ‘C’, the head of MI6. Perhaps surprisingly, this

was in fact no secret within the limited confines of what was then described as

‘polite society’. But Sinclair was far better known among his immediate circle of

friends for his reputation as a man with a taste for the high life. They christened

him Quex after the title character in Arthur Pinero’s popular play The Gay Lord

Quex, who was described as ‘the wickedest man in London’.

This passion for the high life, and the fact that he had the personal wealth to

fund it, dominated Sinclair’s dealings with the codebreakers – an earlier

headquarters had been based in the Strand in central London, apparently for no

other reason than that it was close to the Savoy Grill, one of his more favoured

haunts. Unable to persuade anyone in government to pay for the codebreakers’

new country mansion, he dipped into his own pockets to buy it, immediately

moving his favourite chef from the Savoy Grill to Bletchley Park to ensure that

the codebreakers were well fed.

The result was an atmosphere at the highly secret Station X not unlike that

of a weekend party at an English country mansion. The initial number of

codebreakers in what was known for security reasons as ‘Captain Ridley’s

Shooting Party’ was little more than 200. They lived in hotels in the surrounding

towns and all initially worked either in the mansion itself or in a neighbouring

boys’ school that had been commandeered for the purpose. When not breaking

codes, or if simply seeking somewhere to contemplate their cryptographic

puzzles, the codebreakers could wander through the lawned grounds of

Bletchley Park, which included a maze, a lake and a number of rose gardens.

This brief idyll was shattered in part when the chef, unable to cope with the

sometimes unusual demands of the more idiosyncratic ‘guests’ at Bletchley,

attempted to commit suicide. But other factors were far more crucial in the

transformation that was about to take place. As the Phoney War drew to a close

and Hitler turned his attention to Western Europe, Britain’s back was very much

against the wall. The need to break Enigma and to obtain a permanent source of

high-grade intelligence on German movements was paramount.

Bletchley Park was soon swamped by new recruits, some of whom had

experience within those British companies which were adopting more efficient

business practices pioneered in America. By the time the pre-war British

codebreakers such as Dilly Knox made the first British breaks into Enigma,

Bletchley Park’s operations were already turning into a production line. The

grounds increasingly resembled a building site. The maze and rose gardens

disappeared to be replaced by prefabricated wooden huts in which worked

thousands of people, the vast majority of them women.

The popular view of Bletchley Park, as an organization manned by brilliant

but amateurish eccentrics, is misleading. Certainly early on the organization was

dominated by eccentrics such as Knox and Alan Turing, but the incredible

progress made by some of them not just with Enigma but also with the

development of Colossus, the world’s first programmable electronic computer,

gives the lie to suggestions of amateurism. The vast majority of those working at

Bletchley Park were in fact neither amateurish nor eccentric, although many

were indeed brilliant.

The work they did to unravel the intricate workings of the Enigma cipher

machine is estimated to have cut around two years off the length of the war in

Europe. But that is only part of the story. The British codebreakers were not just

working on German codes and ciphers, they were breaking those of all of

Germany’s allies in Europe: Italy; Hungary; Romania; Bulgaria; and initially, of

course, the Soviet Union, as well as those of neutral countries such as Sweden,

Spain and Portugal. The codes and ciphers of a number of non-European

countries were also coming under the scrutiny of the British codebreakers, and

the most important by far of these was Japan.

Almost a year before Pearl Harbor, the British and the Americans had

agreed in principle to share their codebreaking resources. The two most

Description:In this gripping, previously untold story from World War II, Michael Smith examines how code breakers cracked Japan’s secret codes and won the war in the Pacific. He also takes the reader step by step through the process, explaining exactly how the code breakers went about their daunting taskmad