Table Of ContentThe Cockfight

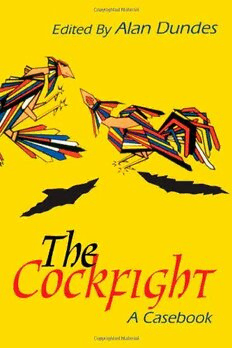

Balinese wood carving in the collection ofW. M. C. and Donna Dickinson. Photograph

by Gene Prince.

Edited by Alan Dundes

The Cockfight

A Casebook

The University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press

114 North Murray Street

Madison, Wisconsin 53715

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

Copyright © 1994

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Cockfight: a casebook / edited by Alan Dundes.

302p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-299-14050-4. ISBN 0-299-14054-7 (pbk.)

1. Cockfighting. I. Dundes, Alan.

SF503.C68 1994

791.8-dc20 93-30545

Contents

Preface vii

Acknowledgments x

A Barnyard Cockfight of the Fourth Century 3

St. Augustine

A Cock Fight from the Ming Dynasty 7

Yuan Hung-tao

The Rules of Cockfighting 9

Jim Harris

A London Cockpit and Its Frequenters 17

Pierce Egan

Cock-Fighting in Puerto Rico 26

William Dinwiddie

A Cockfight in Tahiti 30

Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall

California Cockfight 38

Nathanael West

An Irish Cockfight 45

Michael O'Gormon

The Birds of Death 54

Giles Tippette

The Fraternity of Cockfighters: Ethical Embellishments

of an Illegal Sport 66

Charles H. McCaghy and Arthur G. Neal

Questions from a Study of Cockfighting 81

Laurin A. Wollan, Jr.

Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight 94

Clifford Geertz

v

Contents

Cock or Bull: Cockfighting, Social Structure,

and Political Commentary in the Philippines 133

Scott Guggenheim

The Cockfight in Andalusia, Spain: Images of the Truly Male 174

Garry Marvin

Zooanthropology of the Cockfight in Martinique 191

Francis Affergan

The Gaucho Cockfight in Porto Alegre, Brazil 208

Ondina Fachel Leal

Cockfighting on the Venezuelan Island of Margarita:

A Ritualized Form of Male Aggression 232

H. B. Kimberley Cook

Gallus as Phallus: A Psychoanalytic Cross-Cultural

Consideration of the Cockfight as Fowl Play 241

Alan Dundes

A Selected Bibliography 285

Index 289

vi

Preface

The cockfight, in which two equally matched roosters-typically bred and

raised for such purposes and often armed with steel spurs (gaffs)-engage in

mortal combat in a circular pit surrounded by mostly if not exclusively male

spectators, is one of the oldest recorded human games or sports. It is at least

2500 years old, and it appears to have originated somewhere in southeast Asia.

The cockfight may be brief-it can be over in a matter of minutes or even

seconds, but it can also last much longer, e.g., up to half an hour or more, if the

two roosters are both able to avoid serious injury. Banned in many countries on

the grounds that the cockfight constitutes inhumane cruelty to animals, the

activity nevertheless continues to flourish as an underground or illegal sport.

The cockfight is by no means universal, as it is not reported from native North

and South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and northwestern Europe (e.g., Ger

many and Scandinavia). Still, in those areas of the world where cockfighting

thrives, it is virtually the national (male) pastime, e.g., the Philippines, Bali,

Puerto Rico.

The aim of this casebook is to sample some of the scholarship which has

sought to describe and analyze the cockfight. Sources selected range from

chapters in fictional novels to analytic essays which first appeared in profes

sional anthropology and folklore journals. The goal is to give the reader some

idea of the nature of cockfighting in a wide variety of cultural contexts as well

as possible clues as to the meaning(s) of the cockfight as a traditional game/

sport. As these eighteen essays were written at different times (from 386 to

1993) and directed to vastly different audiences, one should expect a lack of

consistency in terms of theoretical orientation. But that is precisely the point.

The reader should come away from the casebook with an appreciation of the

fact that there are numerous ways of analyzing the same data. Because these

diverse essays were written independently of one another for the most part, it

was not possible to avoid some overlap of content and detail. This repetition of

ethnographic material should not be deemed undesirable. That a cockfighting

practice in the Philippines is also reported in India may tell us something

important about the possible historical relationships between these two cock

fighting traditions.

We begin the volume with St. Augustine's fourth-century musings on why

cocks fight in the barnyard and why men are so fascinated by such cockfights.

We then present a short essay from the Ming Dynasty, which again attests

man's attraction to natural cockfights but which raises the question of whether

vii

Preface

or not man should intervene in such events. We then proceed to consider the

cockfight proper, in which the "natural" cockfight has been taken over by

humans so that cocks may act as human surrogates. The first of these essays

gives an account of the rules of cockfighting. While each area of the world or,

for that matter, each arena or "gallodrome" may have its own local rules, the

general principles governing this event are discernible, and it is the purpose of

this essay to familiarize the reader who may never have seen an actual cockfight

with these principles. The next six essays consist of different descriptions of

cockfights. The contexts include early nineteenth-century London, late

nineteenth-century Puerto Rico, and twentieth-century Tahiti, southern Cali

fornia, Ireland, and the Texas-Mexico border. Although several of these ac

counts are literary, they do have the advantage of being vivid and well-written.

Then follows an essay describing the cockfighters themselves and their atti

tudes towards their sport, and how they defend themselves against the charges

made by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. A second essay

in this vein speculates not only about the pros and cons of cockfighting, but

also about whether or not cockfighting should be the legitimate subject of

study by scholars.

The final seven essays in the casebook all seek to analyze (as opposed to

describe) the cockfight. The first of these, by anthropologist Clifford Geertz,

is unquestionably a turning point in the history of cockfighting scholarship.

First published in 1972, it has stimulated an interest in cockfighting outside of

the relatively small world of cockfighters and cockfight fans. Almost all serious

scholarship since 1972 takes Geertz's memorable commentary on the Bali

nese cockfight as a point of departure. Anthropologists Guggenheim, Marvin,

Affergan, Leal, and Cook analyze the cockfight in the Philippines, Spain, Mar

tinique, Brazil, and Venezuela, respectively. Each provides valuable ethno

graphic detail as well as an attempt to decipher the meaning of the cockfight in

a particular cultural context. The final essay, by this volume's editor, seeks to

examine the cockfight as a cross-cultural phenomenon from the vantage point

of a psychoanalytic perspective.

The reader may agree with one, or some, or none oft he authors represented

in this casebook. In the latter instance, he or she may be inspired to propose a

new interpretation of the cockfight, an interpretation not found in this sam

pling of cockfight scholarship. At least, the reader will have an advantage over

most of those who have written on the cockfight in the past, the advantage of

having a knowledge of some of the standard sources devoted to the subject.

Many of the writers of the essays included in this volume appear to have known

only the one cockfighting tradition they discussed.

While some individuals may adjudge the cockfight to be a cruel "male"

game or sport, and as such unworthy of scholarly consideration, the fact is that

viii

Prefoce

the cockfight does exist and has existed for hundreds and hundreds of years.

Folklorists are obliged to study all traditional materials, even those which may

seem unpleasant or inhumane to some. Certainly there is no doubt that the

cockfight is traditional. We cannot possibly hope to understand human behav

ior if we arbitrarily exclude any part of it from study. The cockfight may be

"illegal," but it is perfecdy legal to seek to explain its undeniable appeal to a

substantial segment of the world's population.

ix