Table Of ContentCopyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook edition published by 4th Estate in 2017

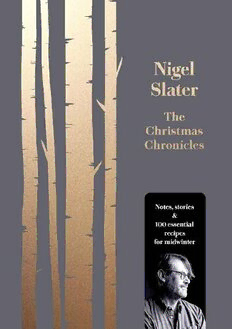

Text copyright © Nigel Slater 2017

Location photographs © Nigel Slater 2017

Recipe photographs © Jonathan Lovekin 2017

Nigel Slater asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of

the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and

read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted,

downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information

storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical,

now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008260194

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008260200

Version: 2017-09-14

For James

Who once told me ‘You can grow old, just make sure you never grow

up.’

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

November

December

January

February

Index

Acknowledgements

Note about the type

About the Book

About the Author

Also by Nigel Slater

About the Publisher

Introduction

The icy prickle across your face as you walk out into the freezing air. The

piercing burn to your sinuses, like wasabi. Your eyes sparkle, your ears

tingle. The rush of cold to your head is stimulating, vital, energising.

The arrival of the first snap of cold is invigorating, like jumping into

an ice pool after the long sauna of summer. Winter feels like a renewal, at

least it does to me. I long for that ice-bright light, skies of pale blue and

soft grey light that is at once calm and gentle, fresh and crisp. Away from

the stifling airlessness of summer, I once again have more energy. Winter

has arrived. I can breathe again.

My childhood memories of summer are few and precious. Picking

blackcurrants for pocket money. A vanilla ice cream, held between two

wafers, eaten on the seafront with my mum, seagulls overhead. Sitting in

a meadow, buttercups tickling my bare legs, eating ham sandwiches and

drinking dandelion and burdock. Pleading with my parents to stop the car

so I could get out and pick scarlet poppies, with petals like butterflies’

wings that wilted before I could get them home. These are virtually the

only recollections I have of those early summers. It is the winters that

stay in my memory, carved deep as a fjord, as long and clear as an icicle.

It is as if my entire childhood was lived out in the cold months, a

decade spent togged up in duffel coats and mittens, wellingtons and

woolly hats. To this day, I am never happier than when there is frost on

the roof and a fire in the hearth. I have always preferred snow underfoot

to sand between my toes.

I love the crackle of winter. The snap of dry twigs underfoot, boots

crunching on frozen grass, a fire spitting in the hearth, ice thawing on a

pond, the sound of unwrapping a Christmas present from its paper. The

innate crispness of the season appeals to me, like newly fallen snow,

frosted hedges, the first fresh page of a new diary. Yes, there is softness in

the cold months, too, the voluminous jumpers and woolly hats, the steam

rising from soup served in a deep bowl, the light from a single candle and

the much-loved scarf that would feel like a burden at any other time of

year.

We all know winter. The mysterious whiff of jasmine or narcissus

caught in the cold air; the sadness of spent, blackened fireworks the

morning after Bonfire Night; a row of pumpkins on a frosted allotment

spied from a train window; the magical alchemy of frost and smoke.

Winter is the smell of freshly cut ivy or yew and the childish excitement

of finding that first, crisp layer of fine ice on a puddle. It is a freckling of

snow on cobbled pavements and the golden light from a window on a

dark evening that glows like a Russian icon on a museum wall. But for

each midwinter sunset, there is another side to this season. Like the one

of 1962–3, when farmers, unable to negotiate deep snowdrifts, wept as

their animals froze to death in the fields; the snap of frail bones as an

elderly neighbour slips on the ice; the grim catalogue of deaths of the

homeless from hypothermia. Winter is as deadly as she is beautiful.

A walk through the snow

It started with berries. Holly, rowan, rosehips. A project to record the

plants, edible and poisonous, that we spotted on our walk to school. Two

miles, in my case, of hedgerows to inspect daily. Hardly a project for me;

I knew those hedgerows intimately, each tree and ditch, every lichen-

covered gate. I knew which had wild sweet peas – Lathyrus odoratus – or

primroses hidden by twigs and where to find a bullfinch’s nest. When you

walk the same route every day on your own, you get to know these

things. A tree you must duck to avoid a soaking if it has rained during the

night; the progress of a slowly decomposing tree stump among the grass;

a bush that delights with a froth of white blossom in spring that by

autumn is a mass of purple-black berries. You get to know the site of the

sweetest blackberries and the exact location of the wild violets, white and

piercing purple, that twinkle like stars in dark holloways.

Even then I knew that hedgerows were sacred, the homes of birds’

nests and voles, hedgehogs and haws. I knew that the long, slim rosehips

came from the single wild roses that are to this day one of my favourite

flowers, along with the hawthorn. I knew too that my father’s name for

hawthorn was ‘bread and cheese’, an ancient reference to the usefulness

of its leaves and berries in winter. I also understood that the scarlet berries

of yew and holly were never, ever, for consumption.

It was the berries left behind in the winter that held a special

fascination for me. The darkening rosehips and hawthorn berries seen

against a tapestry of frosty leaves; the solemn beauty of ivy and

hypericum berries against a grey wall; a rosehip trapped in ice. Walking

was part of my country childhood. A solitary one, but by no means

lonely. Not that there was any choice. My father drove back to the Black

Country during the week. We had just four buses, two on a Wednesday –

one there, one back – and two on Saturday. A bike, you say? Not up the

steep hills that surrounded Knightwick, with a gym bag and a leather

satchel full of books. There were always books. We lived on the border of

two counties. Home and school were in Worcestershire, the nearest shops

in Herefordshire. The walks were wretched in summer, sweaty and

hateful, full of stinging nettles and sunburn, but in autumn and winter

each day was an adventure. I rarely got home before darkness fell. There

was a moment, a patch of barely half an hour, when the sun would burn

fiercely in the winter sky, just before it slid away, that I regarded as

unmissable. Something I had to be outside for.

It was the walk to school that started everything. A life lived with the

rhythm of the seasons. Not purely the food (miles from a supermarket or

a greengrocer, we ate more seasonally than most), but the outdoors too,

the landscape, the garden and the market. The sounds and smells that

mark one season as different from another.

By the way, I kept that school project, neatly written in fountain pen,

its berry-studded exercise books covered in dried leaves and curls of ‘old

man’s beard’, for almost twenty years. Like pretty much everything I

owned, it was destroyed in a house fire shortly after I moved to London.

Getting to grips with the season

Winter is caused by the movement of the Earth, the dark winter months

appearing when the Earth’s axis is at its furthest point from the Sun. For

all its bare twigs and pale, watery sunshine, winter is very much alive.

Underneath the fallen leaves things are happening at a rate of knots; new

life burgeons. Bulbs are sprouting, buds are bursting through grey bark,

new shoots push their way to the surface. Many plants require

vernalisation, a prolonged patch of low temperatures, in order to grow.

Tulips, freesias, crocus and snowdrops, for instance. (I sometimes feel I