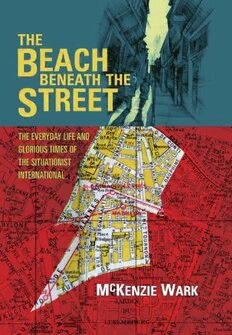

Table Of ContentTHE BEACH BENEATH THE STREET

THE BEACH BENEATH THE STREET

THE EVERDAY LIFE AND GLORIOUS TIMES

OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL

MCKENZIE WARK

London • New York

This edition fi rst published by Verso 2011

© McKenzie Wark 2011

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-720-7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Cochin by MJ Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

Contents

Acknowledgments vii

Introduction: Leaving the Twenty-First Century 1

1 Street Ethnography 7

2 No More Temples of the Sun 19

3 The Torrent of History 33

4 Extreme Aesthetics 45

5 A Provisional Micro-Society 61

6 Permanent Play 75

7 Tin Can Philosophy 83

8 The Thing of Things 93

9 Divided We Stand 109

10 An Athlete of Duration 125

11 New Babylon 135

12 The Beach Beneath the Street 147

Notes 161

Index 191

“Monsters of all lands unite!”

Michèle Bernstein

In memory of:

Helen Mu Sung

Andrew Charker

Stephen Cummins

John Deeble

Colin Hood

Shelly Cox

in girum imus nocte et consumimur igni

Acknowledgements

My only qualifi cation for writing this book is some time spent in a

certain militant organization, then in a bohemian periphery, and sub-

sequently in avant-garde formations that met at the nexus of media,

theory and action. This was all long ago and far away, but nevertheless

my main obligation is to salute some comrades from all three worlds

who taught me invaluable things.

This book is for certain friends from those worlds within worlds

who, for various reasons, fell before their time. Some of their names

are acknowledged in the dedication, others will be known to those who

need to know.

Thanks to Joan Ockman and Mark Wigley for the invitation to give

the Buell Lecture at Columbia University in 2007, from which this

book eventually evolved. Thanks also to my hosts for conversations

at NYU, MIT, UCLA, UC Irvine, Dartmouth, Princeton, Brown,

Parsons School of Design, the New School for Social Research,

Laboral, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Cabinet, and 16 Beaver.

Thanks to my Lang College students, past and present.

Earlier versions of some material appeared in Multitudes, Angelaki, as

an introduction to Guy Debord, Correspondence (Semiotext(e)) and in

my booklet 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International (Prin-

ceton Architectural Press).Thanks to readers for useful comments,

which led to substantial modifi cations.

Special thanks to Kevin C. Pyle for collaborating on Totality for Kids,

part of which appears here as the cover The Situationists détourned

comics by inserting their own texts into the speech bubbles. Kevin

and I reverse the process. The words I have mostly détourned from

Situationist classics. Kevin’s art is the new element.

Thanks for research assistance to Whitney Krahn and in particular

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Julia P. Carrillo. Also to librarians at Bobst, Brown, Columbia and

MoMA, and to innumerable Lang colleagues for their advice, whether

I followed it correctly or not. Thanks to The New School for a faculty

research grant, and to Warhol Foundation | Creative Capital for an art

writer’s grant.

When I gave Tino Sehgal a copy of 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situ-

ationist International one day in Central Park, he exclaimed at once:

“May there be fi fty years more!” My thanks to Tino for the invitation to

interpret his work This Situation at the Marian Goodman Gallery, and

to all of the other interpreters and visitors for many hours of underpaid

but stimulating conversation about “the situation.”

I would also like to offer a special thanks to those who, in the true

spirit of potlatch, translate and archive Situationist writings and make

them freely available: The Bureau of Public Secrets, Infopool, Not

Bored, The Situationist International Online Archive, Unpopular

Books and others.

Lastly, a shout out to Brooklyn Rod and Gun Club and the Lake-

house Commune, and most of all: love to Christen, Felix and Vera.

viii

Introduction: Leaving the Twenty-First Century

A giant infl atable dog turd broke loose from its moorings outside

the Paul Klee Center in Switzerland and brought down power lines

before coming to a halt in the grounds of a children’s home. The Paul

McCarthy sculpture, the size of a house, reached a maximum altitude

of 200 meters. Other civilizations had their chosen forms: from the

Obelisk of Luxor to Michelangelo’s David. The futurist poet Marinetti

found his crashed motor car more beautiful than the Winged Victory of

Samothrace, but he might have balked at fl ying dog shit.1 In the twenty-

fi rst century, the insomnia of reason does not breed monsters, but pets.

No wonder there are no longer any gods, when what is expected of

them is that they descend from Mount Olympus with plastic baggies

and clean up.

We are bored with this planet. It has seen better centuries, and the

promise of better times to come eludes us. The possibilities of this

world, in these times, seem dismal and dull. All it offers at best is spec-

tacles of disintegration. Capitalism or barbarism, those are the choices.

This is an epoch governed by this blackmail: either more and more of

the same, or the end times. Or so they say. We don’t buy it. It’s time to

start scheming on how to leave the twenty-fi rst century. The pessimists

are right. Things can’t go on as they are. The optimists are also right.

Another world is possible. The means are at our disposal. Our species-

being is as a builder of worlds.2

Sometimes, to go forwards, one has to go back. Back to the scene of

the crime. Back to the moment when the situation seemed open, before

the gun went off, before the race of champions started. This is a story

about a small band of artists and writers whose habits were bohemian

at best, delinquent at worst, who set off with no formal training and

equipped with little besides their wits, to change the world. As Guy

1

BEACH BENEATH THE STREET

Debord later wrote: “It is known that initially the Situationists wanted

at the very least to build cities, the environment suitable to the unlim-

ited deployment of new passions. But of course this was not easy and

so we found ourselves forced to do much more.”3

Where does one fi nd this kind of ambition now? These days artists

are happy to settle for a little notoriety, a good dealer, and a retrospec-

tive. Art has renounced the desire to give form to the world. Having

ceased to be modern, and fi nding it too passé to be postmodern, art is

now merely contemporary, which seems to mean nothing more than yes-

terday’s art at today’s prices.4 If anything, theory has turned out even

worse. It found its utopia, and it is the academy. A colonnade adorned

with the busts of famous fathers: Jacques Lacan the bourgeois-

magus, Louis Althusser the throttler-of-concepts, Jacques Derrida the

dandy-of-difference, Michel Foucault the one-eyed-powerhouse,

Gilles Deleuze the taker-from-behind. Acolytes and epigones pace

furiously up and down, prostrating themselves before one master—Ah!

Betrayed!—and then another. The production of new dead masters to

imitate can barely keep up with consumer demand, prompting some

to chisel statues of new demigods while they still live: Alain Badiou the

Maoist-of-the-matheme, Giorgio Agamben the pensive-pedant, Slavoj

Žižek the neuro-Hegelian-joker.5

In the United States the academy spread its investments, placing

a few bets on women and people of color. The best of those—Susan

Buck-Morss, Judith Butler, Paul Gilroy, Donna Haraway—at least

appreciate the double bind of speaking for difference within the heart

of the empire of indifference. At best theory, like art, turns in on itself,

living on through commentary, investing in its own death on credit. At

worst it rattles the chains of old ghosts, as if a conference on “the idea

of communism” could still shock the bourgeois. As if there were still

a bourgeois literate enough to shock. As if it were ever the idea that

shocked them, rather than the practice.6

Beneath the pavement, the beach. It’s a now well-worn slogan

from the May–June events in Paris, 1968, at the moment when two

kinds of critique seemed to come together. One was communist, and

demanded equality. The other was bohemian, and demanded differ-

ence. The former gets erased from historical memory; as if one of the

world’s great general strikes never happened. The latter is rendered

in a language that makes it seem benign, banal even. As if all that was

2