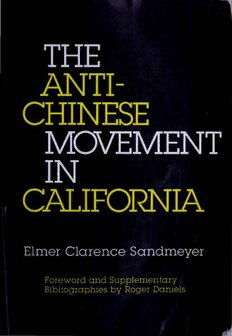

Table Of ContentTHE ANTI-CHINESE MOVEMENT IN CALIFORNIA

THE ANTI-CHINESE MOVEMENT

IN CALIFORNIA

·'

ELMER CLARENCE SANDMEYER

Foreword and Supplementary Bibliographies

by Roger Daniels

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana and Chicago

Illini Books edition, 1991

© 1973, 1991 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

Originally published in a clothbound edition, 1939. ISBN 0-252-00338-1.

Manufactured in the United States of America

p 5 4 3 2

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sandmeyer, Elmer Clarence, 1888-1971.

The anti-Chinese movement in California I Elmer Clarence Sandmeyer;

foreword and supplementary bibliographies by Roger Daniels. -

Illini Books ed.

p. cm.

Enlargement of 1973 publication; originally published in 1939 as

the author's thesis, University of Illinois, 1932.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-252-06226-4

r. Chinese Americans-California-History. 2. California-Race

relations. I. Daniels, Roger. II. Title.

F870.css3 1991

979.4'004951-dc20 91-10876

CIP

..

CONTENTS

FOREWORD by Roger Daniels 3

PREFACE 7

INTRODUCTION 9

l. THE CHINESE COME TO CALIFORNIA 12

II. THE BASES OF ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENT 25

III. CALIFORNIA ANTI-CHINESE AGITATION PRIOR TO 876 40

I

IV. THE NEW CONSTITUTION AND THE CHINESE 57

V. THE ACHIEVEMENT OF RESTRICTION 7 8

VI. FROM RESTRICTION TO EXCLUSION 96

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 109

BIBLIOGRAPHY I I 2

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 1939-72 125

,

by Roger Daniels

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 1972-91 129

,

by Roger Daniels

INDEX 133

FOREWORD

The Anti-Chinese Movement in Historical Perspective

T of the Chinese Exclusion Act ninety years ago was an

HE ENACTMENT

important watershed in the history of American immigration legislation.

(

It marks the beginning of a period of more than eight decades 1882-

1965) in which the immigration policy of the United States was officially

racist. Chinese exclusion was followed by executive agreements to restrain

(

Japanese immigration 1907-08), the "barred zone" act of 1917, which

excluded all other Asians, save Japanese and Filipinos, the National

Origins Act of 1924, which not only included Japanese in the excluded

group but also enacted highly discriminatory quota restrictions against

Caucasian ethnic groups considered inferior. The final escalation of dis

crimination against Asians occurred in 1934, when, under a special pro

vision of the Philippine Independence Act, Filipinos were restricted to

a quota of fifty per year. The first significant relaxation of immigration

laws against Asians took place in 1943, when Congress, in a token gesture

toward a wartime ally, granted China a quota of 100. All Asian nations

got similar quotas under the 1952 McCarran Walter Act. Ethnic quotas,

as such, were abolished in the 1965 revision of the basic immigration

statutes. Under that act fairly large numbers of Chinese have immigrated

to the United States, largely from Hong Kong and Taiwan. In the year

ended June 30, 1970, for example, slightly more than 14,000 Chinese

entered this country as immigrants while an additional 34,000 entered as

non-immigrants.1

Elmer Sandmeyer's 1939 _bgok -the outgrowth of a 1932 dissertation

.

in history at the University of Illinois -was the first modern account of

an important episode in the development of organi�ed racism in the far

western United States. Prior to Sandmeyer, the anti-Chinese movement

had been viewed with distaste by racist nineteenth-century historians like

Hubert Howe Bancroft,2 and had been attacked as bigoted by WASP

historians like Mary Roberts Coolidge, who substituted class biases of

her own. She so little understood the political dynamics of California that

she could write, in I 909, of the anti-} apanese movement then coming to a

head, that it was "after all a superficial demonstration confined to a class

of workingmen, and reflected by political aspirants of the lower grade but

ignored by the majority."3

1 U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, Annual Report (\Vashington, 1970), p. 40.

1 For Bancroft the best introduction is the biography by John \Valton Caughey, Hubert Howe

Bancroft (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1946).

3 Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, 1909), p. 253. Arno Press published

a reprint in 1969.

3

4 THE ANTI-CHINESE MOVEMENT IN CALIFORNIA

Sandmeyer's approach, and it is this that sets his wo�k off from what

had gone before, was not to denigrate but to att�mpt to understand. In

that attempt he largely succeeded. Without in any way "approving" the

anti-Chinese movement, he demonstrated that its roots were in deeply

ielt social and economic grievances. He understood that while "diverse

moti\'es" were responsible for its growth and success, the fundamental

element was racial "antagonism, reinforced by economic competition"

( p. 109). His research, largely in newspapers, pamphlets, government

documents, and the periodical press, established clearly and 0'precisely the

successive marii festations of anti-Chinese sentiment which coalesced into

a movement that triumRhed successive!_). on the local, state; regional, and

finally national level.. If the �riti�g and-.l�vel of analysis are somewhat

pedestrian, the work is accurate, and, in the more than three decades since

its publication, no scholar has thought it necessary to redo Sandmeyer's

effort. :\or is any such re-examination likely.

Only in the last decade, when, for a variety of reasons, historians were

becoming more and more conscious of race and ethnicity 'as important

factors in the American past and present, did monographic literature begin

to appear that significantly supplemented, but did not replace, Sandmeyer's

work. The three most important of these were, in chronological order,

Gunther Barth's Bitter Strength ( I964), Stuart C. Miller's T!tc Un

welcome Immigrant ( r969), and Alexander Saxton's The Indispensable

F'..nemy (1971).4

Barth, a student of Oscar Handlin's, attempted to write a history of

the Chinese in the United States in the first two decades of their experi

ence. Seriously hampered by an almost total absence of documentary evi

dence telling the story from a Chinese point of view, Barth resorted

h('avily to the argument from analogy, comparing Chinese immigration

to the united States with that of Chinese to various parts of southeast

Asia. Heplacing Mrs. Coolidge's Victorian sentimentality with the broad

based social science approach typical of Handlin's students, he charac

terized the Chinese as essentially "sojourners" but eventually becoming

immigrants.

Stuart ;'1.1 iller like Barth eastern-trained, essayed an intellectual his

tory of American attitudes toward the Chinese, as his subtitle shows.

I )espite a great deal of uncertainty-and occasionally error -about

California history, Miller managed, for the first time, to integrate anti

Chinese attitudes into the mainstream of American ideas. While previous

scholarship, including my own, had contended that "racism, as a per

vasive doctrine, did not develop in the United States until after the Civil

•Gunther Barth, Bitter Stt-en9th: A llistory of the Chinese in the U1�ited States, 1850-1.870

(Cambridge, :\lass., 1964); Stuart Creighton Miller, The Unwelcome hmmgrant: The American

[mage of the Chinese, 1785-1882 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1969); Alexander Saxton, The Indis

pensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese A11Y11ement in California (Berkeley and Los Angeles,

1971 ).