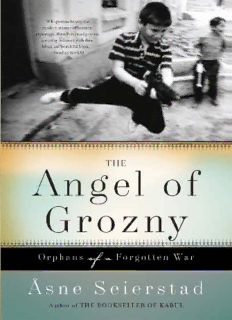

Table Of ContentThe Angel of

Grozny

Other Books by Åsne Seierstad

With Their Backs to the World: Portraits from Serbia

Bookseller of Kabul

A Hundred and One Days” A Baghdad Journal

The Angel of

Grozny

Orphans of a Forgotten War

Åsne Seierstad

Translated by

Nadia Christensen

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

New York

Copyright © 2008 by Åsne Seierstad

Translated © 2008 Nadia Chrijstensen

Published in 2008 in the United States by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Published in 2007 by J. W. Cappelens Forlag

Published in 2008 in Great Britain by Virago Press

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in

critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books,

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016-8810.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts

for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions,

and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special

Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street,

Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000,

or e-mail [email protected].

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN-13: 978-0-465-01122-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008925222

British ISBN: 978-1-84408-395-4

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

1 The Little Wolf 1

2 . . .sharpens his kinzhal 11

3 The First War 28

4 Wolf Hunt 49

5 Return 63

6 The Angel of Grozny 71

7 The Abused 78

8 Living in a Fog 88

9 Friday Evening 96

10 Sleep in a Cold Room– Wake Up in a Cold Room 119

11 Between Mecca and the Kremlin 137

12 The Enemy Among Us 152

13 Welcome to Ramzania 162

14 New Grozny and the Green Zone 173

15 The Youth Palace 179

16 War and Peace 198

17 His Father’s Son 210

18 Tea, Old Woman? 226

19 While Putin Watches 235

20 Honour 246

21 The Fist 253

22 For the Fatherland 291

23 Minus and Plus 311

24 The Little Wolf and the Thief 317

Thank You 341

1

The Little Wolf

T

he blood flows into the mud, where it carves thin red paths.

The slope is dark with mould and decay, and soon the blood will

be absorbed and will disappear. The skull is crushed, the limbs

lifeless. Not so much as a whimper is heard.

Red drops have splashed his trousers, but he can rinse them off

in the water that flows in the flat riverbed below. With the brick

still in his hand he feels strong, invincible and calm. He stands

looking at the lifeless eyes. Blood still trickles out and is sucked

into the sediment. He kicks the corpse and walks down to the

river. The scrawny mongrel will soon be food for new stray dogs,

and later for flies and maggots and other crawling things.

Once, he drowned a cat in a sewage ditch, but it didn’t give

him the same feeling as killing dogs. Now he mostly kills dogs.

And pigeons. They perch by the dozen up in the tall apartment

buildings. He sends them scattering in fright from the kitchen to

the living room to the bedroom and lavatory, right through holes

in damaged walls where the concrete dangles in huge chunks. The

apartments are like half-crushed shells; rows of rooms are no

more than piles of masonry and dust. Everything usable that

wasn’t destroyed in the attacks is stolen, devoured. A few dilap-

idated things remain: a warped stool, a broken shelf.

The buildings were left standing as walls of defence on the flat

2 The Angel of Grozny

landscape when the first rockets were aimed at the city. Here the

city’s defenders barricaded themselves; here, they thought, they

would stop the invasion. Throughout an unyielding, bone-chilling

winter the battles raged from neighbourhood to neighbourhood,

from street to street, from house to house. The resistance fight-

ers had to keep withdrawing further out of the city, surrendering

the rows of deserted apartment blocks like eerie shooting targets

for the Russians’ rockets. In some of the buildings you can still

read the rebels’ graffiti on the walls– Svoboda ili Smert– Freedom

or Death!

On stairways without banisters, on ledges where one false step

means you plummet to the bottom, in rooms where at any

moment the ceiling can collapse on top of him or the floor give

way under him – this is where Timur lives. From the top of the

concrete skeletons he can peer out through holes in a wall at the

people below. When he gets hungry he startles the pigeons,

which flutter away in confusion. He chases them into a corner and

chooses his victim. The fattest. Grasping it tightly between his

legs, he breaks its neck with a practised grip. He twists off the

head, quickly turns the bird upside down, and holds it like that

until all the blood flows out. Then he plucks it, thrusts a stick

through its body and roasts it over a fire he’s lighted on the top

floor whose roof has been blasted off. Sometimes he roasts two.

In the rubbish dump on the hillside below he ferrets out half-

rotten tomatoes, partially eaten fruit, a crust of bread. He

searches in the top layers because the refuse quickly becomes cov-

ered with dust and muck and, when the rain comes, gets mixed

with bits of glass, metal and old plastic bags. The dump is a life-

less place. Only up on the asphalt strip at the top of the steep hill

is there movement. People, cars, sounds. When he’s down here,

amid the rotting earth, he’s hidden from the life up there, the

street life, the human life. Just as on a top floor, almost in the sky,

he’s hidden from the life below.

Quick as a squirrel, slippery as an eel, lithe as a fox, with the

eyes of a raven and the heart of a wolf, he crushes everything he

The Little Wolf 3

comes upon. His bones protrude from his body, he’s strong and

wiry, and always hungry. A mop of dirty blond hair hangs over

two green eyes. His face, with its winsome, watchful expression,

is unsettled by these eyes that flit restlessly to and fro. But they

can also take aim like arrows and penetrate whatever they see. Put

to flight, in flight. Ready for battle.

He knows how to kick well. His best kick he does backwards:

advancing as if to attack with his fists, he suddenly spins round and

thrusts out a leg with a quick movement, striking high and hard

with a flat foot. He practises up in the apartment building, kick-

ing and hitting an imaginary enemy. In his belt he carries a knife;

this and the bricks are Timur’s weapons. His life is a battle with

no rules.

He is too much of a coward to be a good pickpocket. There’s

one thing in particular he’s afraid of– a beating. So he steals only

from those smaller than himself. When it starts to get dark he

waylays the youngest children who beg at the bazaar or by the

bridge across the Sunzha and intimidates them into handing over

the coins they collected during the day. He beats up those who

object or try to evade him, and he hits hard. The unfortunate vic-

tims are left in tears. The young predator slinks away.

Summer is coming, and the little wolf will soon be twelve

years old.

When he was only a few months old, towards the end of 1994, he

heard the first bomb blasts. That first winter of war he lay

wrapped in a blanket on his mother’s lap in a dark cellar while the

sounds assaulting his ears formed his first memories. Before he

could walk he saw people stagger, fall and remain lying on the

ground. His father joined the resistance and was killed in a rocket

attack on Bamut in the foothills of the southwestern mountains

when Timur was one year old. His widowed mother then carried

the boy in a shawl to the home of her husband’s parents. A couple

of years later, she, too, was gone.

Timur spent his early childhood with his grandparents in a

Description:In the early hours of New Year’s 1994, Russian troops invaded the Republic of Chechnya, plunging the country into a prolonged and bloody conflict that continues to this day. A foreign correspondent in Moscow at the time, ?sne Seierstad traveled regularly to Chechnya to report on the war, describin