Table Of ContentTHE ANARCHIST

COLLECTIVES

THE

aHaR(HIST

(OLLf(TMS

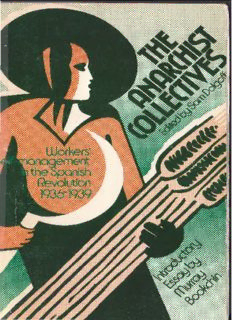

Edited Sam Dolgoff

b~

Workers'

Self-management

in the "SP9nish

Revolution

1936-1939

Int(oductQ(~

Essa~~

mU((O~

Bookchin

To the heroic workers and peasants of Spain!

THE ANARCHIST COLLECTIVES:

To my comrades, the Spanish Anarchists,

Workers' Self-management in

who perished fighting for freedom!

the Spanish Revolution {1936-1939}

To the militants who continue the struggle!

Copyright © 1974 by Sam Dolgoff

Introductory Essay © 1974 by Murray Bookchin

All rights reserved, Free Life Editions, Inc.

First Edition

Published 1974 by Free Life Editions, Inc.

41 Union Square West

New York, N.Y. 10003

Canadian edition published by Black Rose Books by arrangement

with Free Life Editions, Inc.

Black Rose Books

3934 St. Urbain

Montreal 131, Quebec

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-88239

ISBN: 0-914156-02-0 paperback

ISBN: 0-914156-03-9 hardcover

Manufactured in the United States of America

Faculty Press, Inc. Brooklyn, N.Y. ~"J1S9

Contents

PREFACE by Sam Oolgoff- ix

INTRODUCTORY ESSA Y by Murray Bookchin- xi

PART ONE: BACKGROUND

7. THE SPANISH REVOLUTION 5

The Two Revolutions (S.0.}- 5

The Trend Towards Workers' Self-Management (S.0.}- 74

2. THE LIBERTARIAN TRADITION 79

The Rural Collectivist Tradition (S.0.}- 20

The Anarchist Influence (S.0.}- 23

The Political and Economic Organization

of Society (Isaac Puente}- 28

3. HIS TORICA L NOTES 35

The Prologue to Revolution (S.0.}- 35

The Counter-Revolution and the

Destruction of the Collectives (S.0.}- 40

4. THE LlMITA TlONS OF THE REVOLUTION

(Gaston Leval) 49

PART TWO: THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION

5. THE ECONOMICS OF REVOLUTION 65

Economic Structure and Coordination

(Augustin Souchy}- 66

A Note on the Difficult Problems of

Reconstruction (Diego Abad de Santillan}- 69

Money and Exchange (S.0.}- 70

6. WORKERS' SELF-MANAGEMENT IN INDUSTRY

(Augustin Souchy) 77

7. URBAN COLLECTlVIZA TlON

85

Collectivizations in Catalonia (Augustin Souchy)- 86

Preface

The Collectivization of the Metal and

Munitions Industry (Augustin Souchy)- 96

The Collectivization of the Optical

I nd u stry (Collectivizations)- 99

The Socialization of Health Services (Gaston Leval)- 99

Industrial Collectivization in Alcoy (Gaston Leval)- 702

Control of Industries in the North (Jose Pierats)- 707 The Spanish Social Revolution has been long neglected in English

8. THE REVOLUTION OF THE LAND (Jose Pierats) 77 7 language works. Its importance as a revolutionary event and model, and as

a concrete example of workers' self-management by the people is just not

9. THE COORDINA TlON OF COLLECTIVES 727

recognized. My purpose in this collection is to provide an introduction to

The Peasant Federation of Levant (Gaston Leval)- 722

this unique experience. In my first chapter and friend Bookchin's

The Aragon Federation of Collectives:

introductory essay, a general overview and context is presented. Most

The First Congress (Jose Pierats)- 726

important, of course, is that this was a real experience for the people who

70. THE RURAL COLLECTIVES 729

took part. Through their words and deeds and the observations of the

A Journey Through Aragon (Augustin Souchy)-730 authors used in this collection, it is hoped that the reader will gain a

The Collectivization in Graus meaningful understanding of the aims and organization of the anarchist

(Gaston Leval and Alardo Prats)- 735 collectives.

Libertarian Communism in Alcora The material has been divided into two main sections. The first provides

(H.E. Kaminski)- 743 essential background information: the nature of the Spanish Revolution,

The Collective in Binefar (Gaston Leval)- 746 the collectivist tradition, the development of the libertarian labor

Miralcampo and Azuqueca . movement in Spain, and the historical events leading up to and then

culminating in the destruction of the collectives.

(Cahiers de L 'Humanisme Libertaire}- 750

The second, and main, section deals with the actual social

Collectivization in Carcagente (Gaston Leval)- 757

revolution- the overall characteristics of agrarian collectivization and

Collectivization in Magdalena de Pulpis

industrial socialization. It begins with a discussion about economic

(Gaston Leval )- 75 5

coordination, the place and nature of money in the collectives, and

The Collective in Mas de Las Matas (Gaston Leval)- 760

includes statistics on the number of collectives. It then deals with actual

77. AN EVALUA TlON OF THE

descriptions of life in the collectives, first under industrial socialization,

ANA RCHIST COLLECTI VES 765 and then in the rural collectives: how the new institutions were

The Characteristics of the Libertarian Collectives established, how they functioned, how production and distribution were

(Gaston Leval)- 766 handled; about coordination, exchange, relations between collectives, and

In Conclusion (5.0.)- 770 between collectivized and non-collectivized areas. The book ends with a

short evaluation of the anarchist collectives with some comments on their

BIBLIOGRAPHY 777 relevance and lessons.

The glossary, bibliography and appendices add to the overall usefulness

INDEX 783

of this volume. The photographs reproduced within begin to correct the

Appendices appear on pages 11, 29, 30, 71, and 81.

visual bias that has left a plethora of war scenes but very little reflecting

Photographs and posters appear on pages 4,15,25,34,45,64,72, the constructive aspects of the Spanish Social Revolution. Most of the

97,103,104,110,117,141,142,157,158, 173,and 197.

pictures are from contemporary sources held by the editor. I would like to

thank Victor Berch, Special Collections Librarian at Brandeis University

for permission to use the pictures on pages 104, 141, and 142.

The observers speaking in these selections visited the same regions and Introductory Essay

often the same collectives at different times within the short span of

approximately two years. Since each observer stressed what seemed most by Murray Bookchin

important to him, their accounts supplement each other, thus providing a

more balanced view of,tthe new way of life than any single observer could

have done. Under these circumstances, though, some repetition is

inevitable. The translations I have made are strict to the meaning, but are

not literal, for I have also been concerned with giving the spirit of the

words, and with reducing repetitions.

Finally I would like to express my thanks to all the farsighted and brave

people whose work I have used in putting together this collection. (A short

biography on each is included in the bibliography.) Their efforts have

immortalized a social experience of momentous importance. My object has

been to present them to the English reader within a context that will be

useful. In the morning hours of July 18,1936, General Francisco Franco issued

the pronunciamiento from Las Palmas in Spanish North Africa that openly

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS launched the struggle of Spain's reactionary military officers against the

legally elected Popular Front government in Madrid.

It is with the deepest appreciation that I acknowledge the contributions The Franco pronunciamiento left little doubt that, in the event of

to the present work of the following persons: victory by the Spanish generals, a parliamentary republic would be replaced

My friend, Chuck Hamilton, for his tireless technical and editorial by a clearly authoritarian state, modelled institutionally on similar regimes

labors in turning a poorly typed manuscript into the finished book. in Germany and Italy. The Francista forces or "Nationalists," as they were

To my friend, Dr. Paul Avrich, for reading the manuscript and making to call themselves, exhibited all the trappings and ideologies of the fascist

valuable suggestions. movements of the day: the raised open-palm salute, the appeals to a

To my comrade, Murray Bookchin, who first encouraged me to "folk-soil" philosophy of "order, duty, and obedience," the avowed

undertake th is project. commitments to smash the labor movement and end all political dissidence.

Last, but by no means least, my wife Esther who scrupulously To the world, the conflict initiated by the Spanish generals seemed like

examined the manuscript aS'it was'being written and detected many errors. another of the classic struggles waged between the "forces of fascism" and

the "forces of democracy" that had reached such acute proportions in the

thirties. What distinguished the Spanish conflict from similar struggles in

Italy, Germany, and Austria was the massive resistance the "forces of

democracy" seemed to oppose to the Spanish military. Franco and his

military co-conspirators, despite the wide support they enjoyed among the

officer cadres in the army, had grossly miscalculated the popular opposition

they would encounter. The so-called "Spanish Civil War" la'sted nearly three

New York City

years- from July 1936 to March 1939- and claimed an estimated million

January, 1974

lives.

xi

xii / Introductory Essay Introductory Essay / xiii

For the first time, so it seemed to many of us in the thirties, an entire workers and peasants had made a sweeping social revolution. They had

people with dazzling courage had arrested the terrifying success of fascist created their own revolutionary social forms to administer the country as

movements in central and southern Europe. Scarcely three years earlier, well as to wage war against a well-trained and well-supplied army. The

Hitler had pocketed Germany without a shred of resistance from the "Spanish Civil War" was not a political conflict between a liberal democracy

massive Marxist-dominated German labor movement. 'Austria, two years and a fascistic military corps, but a deeply socio-economic conflict between

before, had succumbed to an essentially authoritarian state after a week of the workers and peasants of Spain and their historic class enemies, ranging

from the landowning grandees and clerical overlords inherited from the past

futile street-fighting by Socialist workers in Vienna. Everywhere fascism

to the rising industrial bourgeoisie and bankers of more recent times.

seemed "on the march" and "democracy" in retreat. But Spain had

seriously resisted- and was to resist for years despite the armaments, The revolutionary scope of this conflict was concealed from us- by "us"

aircraft, and troops which Franco acq uired from I taly and Germany. To refer to the many thousands of largely Communist-influenced radicals of

radicals and liberals alike, the "Spanish Civil War" was being waged not only the "red" thirties who responded to the struggle in Spain with the same

on the I berian pen insula but in every country where "democracy" seemed fervor and agony that young people of the sixties responded to the struggle

threatened by the rising tide of domestic and international fascist in Indochina. We need not turn to Orwell or Borkenau, radicals of

movements. The "Spanish Civil War," we were led to believe, was a struggle obviously strong anti-Stalinist convictions, for an explanation. Burnett

between a liberal republic that was valiantly and with popular support Bolloten, a rather politically innocent United Press reporter who happened

trying to defend a democratic parliamentary state against authoritarian to be stationed in Madrid at the time, conveys his own sense of moral

generals- an imagery that is conveyed to this very day by most books on the outrage at the misrepresentation of the Spanish conflict in the opening lines

subject and by that shabby cinematic documentary, To Die in Madrid. of his superbly documented study, The Grand Camouflage:

What so few of us knew outside of Spain, however. was that the

"Spanish Civil War" was in fact a sweeping social revolution by millions of Although the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July, 1936, was

workers and peasants who were concerned not to rescue a treacherous followed by a far-reaching social revolution in the anti-Franco

camp- more profound in some respects than the Bolshevik Revolution

republican regime but to reconstruct Spanish society along revolutionary

in its .ea~ly stages- millions of discerning people outside of Spain were

lines. We would scarcely have learned from the press that these workers and

ke~t In Ignorance, not only of its depth and range, but even of its

peasants viewed the republic almost with as much animosity as they did the

eXistence, by virtue of a policy of duplicity and dissimulation of

Francistas. Indeed, acting largely on their own initiative against which there is no parallel in history.

"republican" ministers who were trying to betray them to the generals, they Fore'most in practicing this deception upon the world and in

had raided arsenals and sporting-goods stores for weapons and with misrepresenting in Spain itself the character of the revoluti~n were

incredible valor had aborted the military conspiracies in most of the cities t~e Communists, who, although but an exiguous minority wh~n the

and towns of Spain. We were almost totally' oblivious to the fact that these CIVil War began, used so effectually the manifold opportunities which

workers and peasants had seized and collectivized most of the factories and that very upheaval presented that before the close of the conflict in

land in republican-held areas, establishing a new social order based on direct ~ 939 they became, behind a democratic frontispiece, the ruling force

In the left camp.

control of the country's productive resources by workers' committees and

peasant assemblies. Whi.le the republic's institutions lay in debris, abandoned

The details of this deception would fill several large volumes. The silence

by most of its military and police forces, the workers and peasants had

that gathers around Spain, like a bad conscience, attests to the fact that the

created their own institutions to administer the cities in republican Spain,

events are very much al ive-together with the efforts to misrepresent them.

formed their own armed workers' squads to patrol the streets, and

After nearly forty years the wounds have not healed. In fact, as the recent

established a remarkable revolutionary militia force to fight the Francista

revival of Stalinism suggests, the disease that produced the purulence of

forces-a voluntaristic militia in which men and women elected their own

counter-revolution in Spain still lingers on the American left. But to de~1

commanders and in which military rank conferred no social, material, or

with the Stalinist counter-revolution in Spain is beyond the scope of these

sYrTlbolic distinctions. Largely unknown to us at that time, the Spanish

xiv / Introductory Essay Introductory Essay / xv

introductory remarks. Fortunately, the bibliography furnished by Sam workers' control and collectives had been advocated for nearly three

Dolgoff provides the English-speaking reader with a number of the more generations by a massive libertarian movement and became the most serious

important works on this subject. I t might be useful, however, to examine issues to divide the so-called "republican" camp, (together w.ith the fate of the

the revolutionary tendencies that unfolded prior to July 1936 and explore militia system). Owing to the scope of its libertarian social forms, the

the influence they exercised on the Span ish working class and peasantry. Spanish Revolution proved not only to be "more profound" (to borrow

The collectives described in this book were not the results of virginal Bolloten's phrase) than the Bolshevik Revolution, but the influence of a

popular spontaneity, important as popular spontaneity was, nor 'were they deeply rooted anarchist ideology and the intrepidity of anarchist militants

nourished exclusively by the collectivist legacy of traditional Spanish village virtually produced a civil war within the civil war.

society. Revolutionary ideas and movements played a crucial role of their

own and their influence deserves the closest examination. Indeed, in many respects, the revolution of 1936 marked the culmination

of more than sixty years of anarchist agitation and activity in Spain. To

The Spanish generals started a military rebellion in July 1936; the understand the extent to which this was the case, we must go back to the

Spanish workers and peasants answered them with a social revolution- and early 1870's, when the Italian anarchist, Giuseppi Fanelli, introduced

this revolution was largely anarchist in character. I say this provocatively Bakunin's ideas to groups of workers and intellectuals in Madrid and

even though the Socialist UGT was numerically as large as the Barcelona. Fanelli's encounter with young workers of the Fomento de las

anarcho-syndicalist CNT.l During the first few months of the military Artes in Madrid, a story told with great relish by Brenan, isalmsot

rebellion, Socialist workers in Madrid often acted as radically as legendary: the volatile speech of the tall bearded Italian anarchist who

anarcho-syndicalist workers in Barcelona. They established their own hardly knew a word of Spanish to a small but enthusiastic audience that

militias, formed street patrols, and expropriated a number of strategic scarcely understood his free-wheeling mixture of French and Italian. By dint

factories, placing them under the control of workers' committees. Similarly, of sheer mimicry, tonal inflections, and a generous use of cognates, Fanelli

Socialist peasants in Castile and Estramadura formed collectives many of managed to convey enough of Bakunin's ideals to gain the group's

which were as libertarian as those created by anarchist pea,sants in Aragon adherence and to establish the founding Spanish section of the International

and the Levant. In the opening "anarchic" phase of the revolution, so Working Men's Association or so-called "First International." Thereafter,

similar to the opening phases of earlier revolutions, the "masses" tried to the "Internationalists," as the early Spanish anarchists were known

assume direct control over society and exhibited .a remarkable elan in expanded rapidly from their circles in Madrid and Barcelona t05pain as ~

improvising their own libertarian forms of social administration. whole, taking strong root especially in Catalonia and Andalusia. Following

Looking back beyond this opening phase, however, it is fair to say that the definitive split between the Marxists and Bakuninists at the Hague

the durability of the collectives in Spain, their social scope and the Congress of the IWMA in September 1872, the Spanish section remained

resistance they offered to the Stalinist counter,revolution, depended largely predominantly Bakuninist in its general outlook. Marxism did not become a

on the extent to which they were under anarchist influence. What significant movement in Spain until the turn of the century and even after it

distinguishes the Spanish Revolution from those which preceded it is not became an appreciable force in the labor movement, it remained largely

only the fact that it placed much of Spain's economy in the hands of reformist until well into the thirties. During much of its early history, the

workers' committees and peasant assemblies or that it established a strength of the Spanish Socialist Party and the UGT lay in administrative

democratically elected militia system. These social forms, in varying degrees, areas such as Madrid rather than in predominantly working-class cities like

had emerged during the Paris Commune and in the early period of the Barcelona.2• Marxism tended to appeal to the highly skilled, pragmatic,

Russian .Revolution. What made the Span ish Revolution unique is that

2Madrid, although with a largely Socialist labor movement, was the home of an

1 Both the UGT and the CNT probably numbered over a million members each by the intensely active anarchist movement. Not only were the Madrid construction workers

summer of 1936. The officious, highly bureaucratic UGT tended to overstate its strongly anarchosyndicalist, but at the turn of the century, many Madrid intellectuals

membership figures. The more amorphous decentralized CNT - the most persecuted were committed to anarchi~m and established a renowned theoretical tradition for the

of the two labor federations-often exercised much greater influence on the Spanish movement that lingered on long after anarchist workers had cut their ties with the

working class than its membership statistics would ,eem to indicatp.. Spanish intelligentsia.

xvi /Introductory Essay Introductory Essay / xvii

rather authoritarian Castilian; anarchism, to the unskilled, idealistic Catalans m~re rapidly the peasantry became a hereditary proletariat, "disciplined,

and the independent, liberty-loving mountain villagers of Andalusia and the united, organized by the very mechanism of the process of capitalist

Levant. The great rural masses of Andalusian day-workers or braceros, who production itself" (-Marx)-a distinctly hierarchical and authoritarian

remain to this day among the most oppressed and impoverished strata of "mechanism"-the more rapidly Spain would advance to the tasks of

European society, tended to follow the anarchists. But their allegiances socialism.

varied with the fortunes of the day. I n periods of upheaval, "they swelled the Spanish anarchism, by contrast, followed a decisively different approach.

ranks of the Bakuninist IWMA and its successor organizations in Spain, only It sought out the precapitalist collectivist traditions of the village, nourished

to leave it in equally large numbers in periods of reaction. what was living and vital in them, evoked their revolutionary potentialities

Yet, however much the fortunes of Spanish anarchism varied from region as liberatory modes of mutual aid and self-management, and deployed them

to region and from period to period, whatever revolutionary movement to vitiate the obedience, hierarchical mentality, and authoritarian outlook

existed in Spain during this sixty-year period was essentially anarchist. Even fostered by the factory system. Ever mindful of the "embourgeoisment" of

as anarchism began to ebb before Marxian social-democratiC and later the proletariat (a term continually on Bakunin's lips in the late years of his

Bolshevik organizations after the First World War period, Spanish anarchism life), the Spanish anarchists tried to use the pre-capitalist traditions of the

retained its enormous influence and its revolutionary elan. Viewed from a peasantry and "Working class against the assimilation of the workers' outlook

radical standpoint, the history of the Spanish labor movement remained to an authoritarian industrial rationality. In this respect, their efforts were

libertarian and often served to define the contours of the Marxist favored by the continuous fertilization of the Spanish proletariat by rural

movements in Spain.-"Generally speaking, a small but well-organized group workers who renewed these traditions daily as they migrated to the cities.

of Anarchists in a Socialist area drove the Socialists to the Left," observes The revolutionary elan of the Barcelona proletariat- like that of the

Brenan, "whereas in predominantly Anarchist areas, Socialists were Petrograd and Parisian proletariat-was due in no small measure to the fact

outstandingly reformist." I t was not socialism but rather anarchism that that these workers never solidly sedimented into a herditary working class,

determined the metabolism of the Spanish labor movement- the great totally removed from pre-capitalist traditions, whether of the peasant or the

general strikes that swept repeatedly over Spain, the recurring insurrections craftsman. Along the Mediterranean coastal cities of Spain, many workers

in Barcelona and in the towns and villages of Andalusia, and the gun battles retained a living memory of a non-capitalist culture-one in which each

between labor militants and employer-hired th~gs in the Mediterranean mo.ment of life was not strictly regulated by the punch clock, the factory

coastal cities. whlst.le: the foreman, the machine, the highly regulated workday, and the

atomizing world of the large city. Spanish anarchism flourished within the

It is essential to emphasize that Spanish anarchism was not merely a tension created by these antagonistic traditions and sensibilities. Indeed

program embedded in a dense theoretical matrix. I t was a way of life: where a "Germanic proletariat" (to use another of Bakunin's cuttin~

partly, the life of the Spanish people as it was lived in the closely-knit phrases) emerged in Spain, it drifted either toward the UGT or the Catholic

villages of the countryside and the intense neighborhood life of the working unions. Its political outlook, reformist when not overtly conservative often

class barrios; partly, too, the theoretical articulation of that life as projected clashed with the more dec/asse working class of Catalonia an'd the

by Bakunin's concepts of decentralization, mutual aid, and popular organs Mediterranean coast, leading to conflicting tendencies within the Spanish

proletariat as a whole.

of self-management. That Spain had a long tradition of agrarian collectivism

is discussed in this book and examined in some detail in Joaquin Costa's . UI~i~ately, in my view, the destiny of Spanish anarchism depended upon

Colectivismo Agrario en Espagna. Inasmuch as this tradition was distinctly Its ability to create liberatarian organizational forms that could synthesize

pre-capitalist, Spanish Marxism regarded it as anachronistic, in fact, as the precapitalist collectivist traditions of the village with an industrial

"historically reactionary." Spanish socialism built its agrarian program economy and a highly urbanized society. I speak here of no mere

around the Marxist tenet that the peasantry and its social forms could have programmatic "alliance" between the Spanish peasantry and proletariat but

no lasting revolutionary value until they were "proletarianized" and more organically, of new organizational forms and sensibilities that imp~rted

"ind ustrial ized." Indeed, the sooner the vi 11 age decayed the better and the a revolutionary libertarian character to two social classes who lived in

Description:Collectivizations in Catalonia (Augustin Souchy)- 86 . radicals and liberals alike

, the "Spanish Civil War" was being waged not only on the I berian pen insula