Table Of ContentTheJapanTimes

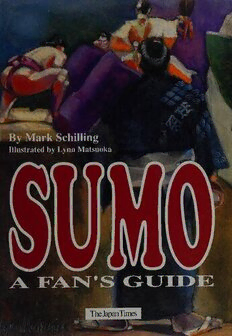

By Mark Schilling

Illustrated by Lynn Matsuoka

A FAN’S GUIDE

The Japan Times

First edition, May 1994

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1994 by Mark Schilling and illustrations by Lynn Matsuoka

Cover design by Keiichiro Uekawa

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy,

mimeograph, or any other means,

without permission.

For information, write: The Japan Times, Ltd.,

4-5-4 Shibaura, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108, Japan.

ISBN 4-7890-0725-1

Published in Japan by The Japan Times, Ltd.

Printed in Japan

Table of Contents

Introduction ix

I Watching and Understanding Sumo 7

The Play: A Typical Bout 2

Winning Sumo 6

Kinjite (illegal techniques) 9

Yotsu-zumo 10

Kimarite 12

Dohyo: The Sumo Stage 13

Dohyo Matsuri and Furedaiko 75

The Mizuhikimaku and Tassels 76

II The Players on the Sumo Stage .... 77

The Players (Rikishi from Maezumo to Makunouchi) /8

Recruiting 18

Maezumo 79

Shinjo Shusse 79

Banzuke 21

Jonokuchi and Beyond 22

Sumo School 22

Tsukebito 22

Up the Ladder to Makushita 25

Juryo: The Promised Land 26

Keshomawashi 27

VI

Mawashi (belts) 29

Maegashira and Above: Hitting the Heights 30

Makunouchi Dohyo-iri (ring-entering ceremony) 31

Sanyaku 32

Yokozuna: The Origins 34

Yokozuna: The Rank 34

TheTsuna 39

The Yokozuna Dohyo-iri (ring-entering ceremony) 40

Yokozuna Perks and Privileges 41

The Players Part II: Behind the Scenes 43

Gyoji 43

Yobidashi: The Hardest Working Men in Sumo 47

Shinpan: The Men in Black 49

Off the Dohyo Not So Rugged Individualists 52

Ichimon and Heya 53

Becoming an Oyakata 55

Heya 56

A Day in the Life 59

Keiko (practice sessions) 6 7

A Drug-Free Sumo World 66

The Rest of the Day 66

III Private and Not-So-Private Sumo

Facts. 71

Healthy Sumo 72

Rikishi and the Opposite Sex 76

Fixing Sumo 80

Shikona: Sumo Names 85

Sumo Salaries 89

Live Sumo 94

Hana-zumo 97

Jungyo 99

Keiko (practice) 101

VII

IV A Brief History of Sumo 103

The Beginnings 104

Kanjin-zumo 108

From the Meiji to the Modern Era / / 7

Advanced Sumo Jargon 116

Winning Techniques (Kimarite) 126

Basic Techniques 127

Nagewaza (throwing techniques) 130

Kakewaza (tripping techniques) 134

Soriwaza (bending techniques) 141

Hineriwaza (twisting techniques) 143

Special Techniques 150

Other Techniques 154

Sumo Records 155

Heya Names and Addresses 157

Bibliography 159

About the Author 160

Addresses and Phone Numbers 161

Index 163

To my parents

Introduction

Sumo would seem to be the simplest of sports. When I first saw it,

on a battered TV set in a Kichijoji noodle shop nearly two decades

ago, I didn't need a doctorate in Japanese studies to get the point:

two big men collide in the center of a circle and the first to throw

or push his opponent down or out wins. American football, with

its headbanging guards, was one point of comparison, King-of-

the-Mountain another.

But I also saw that sumo was different, very different. Profession¬

als in other sports don't wear the hairstyles, observe the customs

and in general live the lives of their 18th-century predecessors.

They don't often go mano a mano against opponents twice their

size. They don't usually grow to Orson Wellesian proportions

(neither do many sumo wrestlers, but more on that later).

The more I watched, the more I wanted to know and the more I

learned, the more I realized that this 2,000-year-old sport wasn't

so simple after all.

What were those brightly colored belts that made the wrestlers

look like overstuffed Christmas presents? Who was that little man

with the paddle, scampering about like a terrier at a fight between

two pit bulls? I wouldn't have asked such questions of baseball or

football — I had grown up with them, watched them before I

knew how to talk. And even if I didn't know the infield fly rule, I

would have been embarassed to ask (as an American male, I was

expected to know).

Sumo, however, was different. As I kept asking questions, I

learned that it was a world with its own history, traditions, mores.

Unlike other professional athletes, who live as members of con¬

temporary society and can even disappear into its crowds, rikishi

(which is what the wrestlers call themselves) remain apart, en¬

closed in a feudal microcosm, a remnant of a vanished world.

Their size, topknots, clothes, even the fragant pomade called

bintsuke that they use on their hair, make them stand out wherever

they go. To today's Japanese, rikishi are exotic beings and the

sumo way of life, with its mix of ancient and modern, is fascinat¬

ingly, even forbiddingly strange.

And yet sumo also offered a window into Japan. Since the open¬

ing of their country nearly a century and a half ago, the Japanese

have adopted many Western ways. To newcomers from abroad,

however, those ways can be a barrier to understanding; Japan's

Westernization may not always be only on the surface, but it is

seldom what it seems. Yes, they eat Big Macs and drink Cokes and

wear Levis, just like we do, but as American journalist James

Fallows once observed, they are still far from becoming us. The

sumo world, which makes no pretenses of Westernization (unless

a Walkman over a topknot is Westernization), offers outsiders a

clearer view of certain only-in-Japan realities.

This book, however, is less an anthropological or sociological

essay than an attempt to answer the questions that fans, beginners

and old-timers alike, really ask and that I thought might be interest¬

ing to answer. What do the pre-bout rituals mean? What are the