Table Of ContentSavage Portrayals

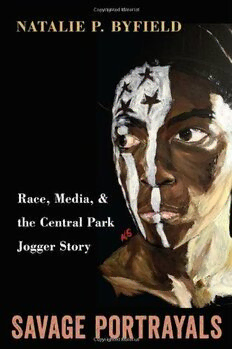

SAVAGE PORTRAYALS

Race, Media, and the

Central Park Jogger Story

NATALIE P. BYFIELD

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Philadelphia

For

Clarence, Kenya, Camara,

and Judi

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122

www.temple.edu/tempress

Copyright © 2014 by Temple University

All rights reserved

Published 2014

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Byfi eld, Natalie P., 1960–

Savage portrayals : race, media, and the Central Park jogger story / Natalie P. Byfi eld.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4399-0633-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4399-0634-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4399-0635-4 (e-book)

1. Central Park Jogger Rape Trial, New York, N.Y., 1990—Press coverage. 2. Rape—

New York (State)—New York—Press coverage—Case studies. 3. Violent crimes—New York

(State)—New York—Press coverage—Case studies. 4. Discrimination in criminal justice

administration—New York (State)—New York—Case studies. 5. African Americans in

mass media. 6. Hispanic Americans in mass media. 7. Racism—United States. I. Title.

HV6568.N5B94 2014

364.15’32097471—dc23 2013016594

Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National

Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ANSI Z39.48-1992

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

Contents

Acknowledgments vii

1 Reconnecting New Forms of Inequality to their Roots 1

2 A Jogger Is Raped in Central Park 28

3 Th e Position of the Black Male in the Cult of White Womanhood 46

4 Salvaging the “Savage”: A Racial Frame that Refuses to Die 75

5 A Participant Observes How Content Emerges 106

6 Th e “Facts” Emerge to Convict the Innocent 129

7 Th e Case Falls Apart: Media’s Brief Mea Culpa 153

8 Selling Savage Portrayals: Young Black and Latino Males

in the Carceral State 168

9 Th ey Didn’t Do It! 182

Notes 199

References 215

Index 227

Acknowledgments

I AM ETERNALLY GRATEFUL for the generosity of spirit of the members of

the Central Park Five—Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Ray-

mond Santana, and Korey Wise—whose lives provided the inspiration for this

project and who have embraced me as I worked to tell a part of their stories.

Th e idea to write about the media coverage of the attack on the Central Park

jogger began for me while I covered the story as a journalist. At that time,

what the account should look like and the message it should deliver were just

a blurry image. My journey to completing this book included many diffi cult

roads that I could not have traveled had it not been for the support of numer-

ous people, whose belief in my project—which sought to forge an alternative

path, away from traditional metanarratives in sociological research—kept me

going through many dark days when the task seemed impossible.

Early support came from members of my dissertation committee at Ford-

ham University, particularly Robin Andersen and E. Doyle McCarthy from the

university’s Communication and Media Studies and Sociology and Anthro-

pology departments, respectively. Since our days in the sociology doctoral pro-

gram, the intellectual generosity of Joyce Weil has been a continuous source of

help to me.

My current home institution, St. John’s University in Queens, New York,

has provided institutional and fi nancial support that has helped bring this proj-

ect to fruition. Th e university’s Institute for Writing Studies has been vital. My

writing partnership with Anne Geller, director of the institute’s Writing Across

the Curriculum, sustained me, particularly during the school year. She heard

and read many versions of signifi cant parts of the manuscript. Her insightful

questions prompted the self-refl ection needed as I worked to create my narra-

tive path. I must also thank the director of the institute’s Writing Center, Harry

viii Acknowledgments

Denny, who helped me wrestle a chapter of the manuscript into shape. A grant

from the St. John’s Center for Teaching and Learning supported my work with

Herstory, the memoir writing group whose structured memoir writing peda-

gogy provided a foundation for some of my work. I am indebted to Herstory

and its founder Erika Duncan, who read and critiqued my early forays into

memoir writing. A grant from the St. John’s Summer Support of Research Pro-

gram was invaluable for helping me complete the project. My department at

St. John’s provided institutional support via several graduate research assis-

tants, particularly Donna Truong and Frances Adomako, who provided im-

portant help. I am very thankful for the encouragement I have received from

colleagues in my department, particularly Roderick Bush, Judith Ryder, and

Roberta Villalón.

I am also indebted to colleagues outside my institution who read draft s of

the proposal and the manuscript and provided guidance, mentorship, and de-

tailed and thoughtful feedback. In particular, the intellectual support and gen-

erosity of Carolyn Brown, Judith Byfi eld, Karen Fields, Venus Green, Wanda

Hendricks, Donna Murch, and Deborah Gray White propelled me forward. In

addition, I thank Deirdre Royster, whose insightful comments early in the pro-

cess were instrumental.

I must express my deep feelings of gratitude to my colleagues, friends, and

family outside of academia, whose various forms of support helped make this

book possible. Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon supported my

project in their own work. In particular, Sarah Burns provided research sup-

port. My editors at Temple University Press have been invaluable. In particu-

lar, I thank Janet Francendese and Mick Gusinde-Duff y, as well as copy editor

Lynne Frost, who have been central. I am also deeply grateful to my extended

family, whose support for me is always palpable. I thank my parents, Hugh

and Ruby Byfi eld; their lifelong support has been inspirational. I also thank

my siblings, Judith, Brian, and Byron. Th e Browne, Dock, Sheppard, White-

head, and Wright families also have been the core of my world for decades and

have kept me going. In particular, my mother-in-law, Sarah Dock, and lifelong

friend Ruth Browne have championed me unfl aggingly. My fi nal words of thanks

go to my husband, Clarence, and my children, Kenya and Camara, to whom

this project is, in part, dedicated. Th eir support throughout this long process

has been breathtaking.

1

Reconnecting New Forms of

Inequality to their Roots

Measuring the Distance between the Eras of

Color-Blind Racism and Jim Crow Racism

THE PERSONAL and professional agendas I pursue in this book grew from a

desire to right a wrong. In 1989, members of the media, as well as portions of

the political establishment and elements of the criminal justice system in New

York City, wrongfully accused a group of black and Latino male teens of sexu-

ally assaulting a white female who had been jogging in Central Park. She would

become known simply as “the jogger.” Six teenage boys were charged with the

crime. Five of them would eventually be convicted in two trials; the sixth would

settle the charges against him in a plea bargain. About thirteen years aft er the

prosecutions, the Manhattan District Attorney’s offi ce petitioned the court to

vacate the convictions because the actual rapist had stepped forward admitting

his guilt. Th is person, a known and convicted serial rapist and murderer already

serving a life sentence, confessed to the attack and said that he had acted alone.

Only his DNA could be connected to the jogger. Despite these developments in

the case in 2002, some members of the political establishment and the criminal

justice system continue to support the wrongful convictions of the young men.

Th e rape of Trisha Meili, a twenty-eight-year-old investment banker work-

ing in Manhattan’s fi nancial district, drew international media attention through

a narrative focused on an allegedly new type of street crime called “wilding.”

Simply put, the term meant intentionally behaving in a crazy manner, causing

harm to others, and damaging property. According to police, the rape of Meili

was the culmination of an evening of wilding in Central Park that began with

other incidents of physical assault and harassment. With that police declaration,

rape and wilding would become joined in the public consciousness. Although