Table Of ContentThis content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sara

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Also available:

Sara

My Whole Life Was a Struggle

Sakine Cansız

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

“Surrender leads to betrayal, resistance to victory”: Cansız with photos of Leyla

Qasim and Mazlum Doğan on the wall behind her, Çanakkale prison, 1990.

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

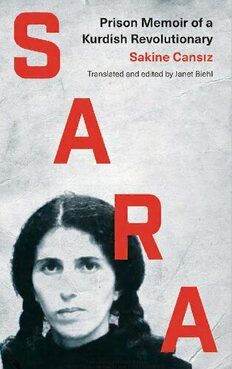

Sara

Prison Memoir of a Kurdish

Revolutionary

Sakine Cansız

Translated and edited by Janet Biehl

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Published in German 2015 by Mezopotamien Verlag as

Mein ganzes Leben war ein Kampf (2. Band – Gefängnisjahre)

First English language edition published 2019 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright © The Estate of Sakine Cansız 2015;

English translation © Janet Biehl 2019

The right of Sakine Cansız to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission

for the use of copyright material in this book. The publisher apologises for any

errors or omissions in this respect and would be grateful if notified of any

corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3984 9 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3983 2 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0492 1 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0494 5 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0493 8 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and

sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to

conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Swales & Willis, Exeter, Devon, UK

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:06 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contents

Translator-editor’s preface viii

Sara 1

Notes 332

List of people 334

List of political names and acronyms 337

Timeline 339

Index 342

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:39 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Translator-editor’s preface

This is the second of three volumes of the memoir of Sakine Cansız, a

remarkable Kurdish revolutionary woman leader. In the first volume,

as readers already know, she described her childhood in Dersim, and

her escapes from marriage in defiance of Turkey’s patriarchal gender

system. She recounts how she became a dedicated organizer for the

group UKO, also known as Kurdistan Revolutionaries, advocating a

socialist revolution in Turkey’s southeast, where many Kurds live. In

November 1978 she attended the founding conference of the UKO’s

successor organization, which would come to be known as the PKK some

18 months later. Sakine moved to Elazığ, a city near her hometown, to

specially focus on organizing women. But in the spring of 1979, Turkish

police began a crackdown on the nascent party, carrying out a wave of

arrests of leading cadres as well as rank-and-file members. On May 7,

in an early morning raid on a movement apartment, police arrested her

along with two other members of the Elazığ group, Hamili Yıldırım and

his wife Ayten. As Volume I ends, the three of them are in a police van

en route to prison, in a state of shock and bewilderment.

At the opening of Volume II, no time has passed—they are still in

the van, which takes them to a prison in Elazığ. That will mark the

beginning of Sakine Cansız’s 12 years of incarceration, the period

covered in Volume II.

She entered the Turkish prison system at a perilous moment. A year

and a half after her arrest, on September 12, 1980, Turkish generals staged

a military coup and declared martial law. They abolished parliament,

suspended the constitution, and banned all political parties and unions.

Most significant for this memoir, they took control of Turkey’s prisons

and militarized them. Prisoners would now be overseen, not by guards

and wardens, but by soldiers. In the days before and after the coup, PKK

leading cadres, including central committee members, were arrested en

masse.

viii

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:34 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

translator-editor’s preface

Surely the most notorious post-1980 military prison was in Diyarbakir,

the largest Kurdish city in southeastern Turkey. Within four months of

the coup, more than 30,000 people were jailed here. PKK leadership

cadre, as well as rank and file, were concentrated here. Sakine Cansız

was taken here around March 1, 1981.

The goal of the militarizing prisons was to strip prisoners of their

rebelliousness, and especially, to strip Kurdish prisoners of their Kurdish

identity, and transform them into obedient, soldier-like Turkish

nationalists. To this end, prison administrators (“the enemy,” as Sara

called them) showed no scruples when it came to violent torture.

Conditions at the Diyarbakir “dungeon,” as the prisoners accurately

referred to it, were the most dire of all. It was not simply that Diyar-

bakir was severely overcrowded. Between 1981 and 1984, the Diyarba-

kir dungeon became notorious for its barbaric cruelty, a “hellhole,”

as it was often called. The military administration inflicted horrific

systematic torture on the prisoners on an unprecedented scale, with

unparalleled methods, both physical and psychological. When detainees

were admitted, for example, they were beaten until their skin was raw,

then thrown into vats of excrement, so that their wounds would become

infected. Then they were made to sing Turkish military marches.

The reader might well set this book down in horror, but that would be

a mistake. While Sara refers to the barbarism, she does not dwell on it.

Other survivors have written memoirs testifying of the barbaric torture

(alas, rarely translated into English), but Sara prefers to focus instead on

the dialectic of capitulation and resistance.

For in the spring of 1979 the nascent PKK had been blindsided. Its

members had not yet had much experience in prison, and its ideologues

and theorists had given scant if any attention to the subject, should its

members ever be imprisoned. They had developed no theory of prison,

no policy for how PKK members were to behave there—not even a clear

analysis demarcating resistance from surrender. As a result, many of the

young Kurdish detainees were understandably terrified and capitulated

under torture, naming names, becoming informers, betraying the

organization.

Sara wanted no part of capitulation, and she herself did not yield under

torture. Instead, she closely observed the behavior of her comrades (or

“friends,” as the Kurdish movement calls them) and tried to discern

the nature of their “weakness,” as she calls it. From the outset she was

ix

This content downloaded from

(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)59.120.225.187 on Tue, 11 Aug 2020 17:43:34 UTC(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)(cid:0)

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms