Table Of Content0~

on'€ s

A FEMINIST JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CRITICISM

Vol. II, No. 4 $2.00

0~

Ol1€'S

Room of One's Own is published quarterly by the Growing

Room Collective. Letters and unpublished manuscripts should

be sent to Room of One's Own, 1918 Waterloo St., Vancouver,

B.C. V6R 3G6. Please enclose a stamped, self-addressed enve

lope for return of manuscripts. Material submitted from outside

Canada should be accompanied by International Reply Coupons,

not stamps.

Subscriptions to Room of One's Own are available through

the above address and are $6.00 per year in Canada, $7 .00 per

year outside Canada. The institutional rate is $10.00 per year.

Back issues available: Vol. I, Nos. l & 2, $2.00 each; Nos. 3 &

4, $1.50 each; Vol. II, No. 1, $2.00 each ; VoL II; No. 3/4,

$3.50 each; single copies to points outside Canada, add $.25 per

copy.

This issue was produced by Laura Lippert, Gayla Reid, Gail

van Varseveld and Eleanor Wachtel, with a little help from Ruth

Brown, Jane Evans, Karen Loder, Maggie Shore and Jo Sleigh.

Printed by Morriss Printing Company, Victoria, B.C.

The Collective wishes to thank the Leon & Thea Koerner Foun

dation for its assistance with this issue and the Canada Council

for its ongoing support.

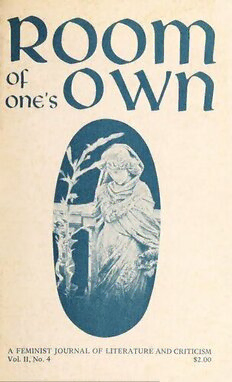

Cover Photo: Eleanor Wachtel

Member of the Canadian Periodical Publishers' Association.

ISSN 0316-1609 Second Class Mail Registration No. 3544

'

© 1977 by the Growing Room Collective.

CONTENTS

The West Coast Trail, Frances Duncan ........ . ..... . . .. 2

Poetry

Alexa De Wiel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Jill Rogers .... . .............................. 13

Norma West Linder ..... ..... ........... .. . . ... 14

Eva Tihany i . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Patricia Monk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Susan Zim1nerman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Alice Gibb . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Carolyn Zonailo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

The Image of Africa in the Fiction of Audrey Thomas,

Eleanor Wachtel ...... ......... .. ....... .... ... 21

T he White Squirrel, Sheila Campbell ... ......... . .... . 29

Feminist Literary Criticism: A Brief Polemic,

Constance Rooke ...................... ...... .. 40

Sue Solon1on, Lake Sagaris ................... ... .. . . 44

Founding Mothers of the English Novel: Mary Manley and

Eliza Haywood, George Woodcock .... ........ ..... 49

The Norwesters, Marsha Mitchell ..................... 66

By Women Writ ... .. ....... ...... ....... ...... ... 70

Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 8

Room of One's Own - 1

The West Coast Trail

Frances Duncan

In late October the West Coast Life-Saving Trail from Port

Renfrew to Bamfield is usually deserted. With good reason. The

weather is not unpredictable ; its rains religiously. But if hikers

are lucky- are proving they can manage the Trail, and so really

do belong there- they are occasionally praised with sun. Then

the beams flicker hot through the cedars and firs and sagging,

dripping moss, light up the puddles, bounce off the creeks and

waterfalls, and turn the mud from faece brown to burnt sienna.

Then the birds sing and the forest smells of glorious decay and

growth, warmed to a temperature the olfactory nerve can

appreciate.

But usually it rains. Thick clouds sit on the treetops and

glower, alternately dripping and deluging, and hike.rs thrash

through the underbrush with small trees thrashing back, and the

path is more that of least resistance for water than for hikers.

So, the Trail after Thanksgiving is left to liberated house

wives who need to prove something to someone-that 1s, to

themselves, for who else cares?

'

Roon1 of One's Own - 2 .

J

Now it is I, Barbara M. acobsen-M. for mysterious per

haps, or madcap, or malevolent even, but certainly not for Mabel

or Margaret or Muriel- who is trudging (a too prosaic term for

what one does on the Life Saving Trail- clambering, panting,

stripped to the essentials; that is, cold and uncomfortable and

wet, thinking of fires, hot rums, bathtubs and beds). I, Barbara

Miserable Jacobsen in the rain, Barbara Marvellous Jacobsen in

my five daily minutes of sun, getting my head together on the

West Coast Trail.

I had left my children to my mother, my husband to his

work, my cat to the neighbour, and .'my house to the cobwebs,

and collected hiking gear from a rental store.

Barbara Mad Jacobsen, slightly, but not definitively fat,

somewhere in the nebulous decades between thirty and fifty,

faintly wrinkled, threatening sags and spare tires, liver spots

and grey hairs, a body halfway through the dying cycle, rebel

ling against the Trail, but not incapable of it.

I was doing the Trail to prove myself, to get my head to

gether. I hadn't realized how much it was apart until I joined a

Consciousness Raising group in honour of International Women's

Year. A case perhaps for ignorance being bliss. There I dis

covered I could not justify myself in terms of the house, the

husband, the children, and certainly not the cobwebs- the

spider's justification. So I said "fuck" and "shit", let the cob

webs dangle, told the children to do their own thing, and

insisted my husband make dinner. But it wasn't enough. Conse

quently the Trail- the ultimate test of independence and ability,

where I hoped to find some justification, if nothing else.

The last person I spoke to was the man who chugged me

across the mouth of the San Juan River. He sneered as I said

good-bye, and I knew he had visions of manning the search

party for my damp and mouldering body when I didn't appear

in Bamfield in a week.

I enjoyed the first half hour and after that knew it was good

for me; if it didn't raise my consciousness it would certainly

raise blisters. The Trail was well-beaten at first and the incline

gradual, then it climbed up cliffs and over creek chasms. Always

the forest sent its underbrush to reclaim it, so I bashed and

slipped through salmonberry and salal, or clambered over detri

tus fallen from the trees which grow and die so fast. My reward

Room of One's Own - 3

was a glimpse of ocean and the dripping silence in a beam of

sun. The Trail and I settled into the long, up and down, wet and

tiring days.

My head, however, did not seem to be getting together very

well, so it was fortunate that I happened upon a new head. It

was supported by a straggly fir and a huckleberry bush which

were trying to grow from a decomposing cedar stump. I looked

around, but there was no one to whom the head could belong,

so I picked it up and screwed it on, leaving my old one in its

place.

Barbara Mutable Jacobsen.

This was the sort of head I would have loved as a teenager.

It had long black hair, a pleasant change from my short frowzy

brown. My new green eyes were elegantly made up with blue

frosted shadow, the lips were full and held in a pout so as not

to smear the lipstick. I ts face was vacuous, except for the bored

promise of interest should a man happen by. I drew in my

stomach and threw out my chest in a attempt to accommodate

my new head.

I had not gone more than a few yards when I realized my

head and I no longer liked the Trail. We were particularly angry

with the rain which was doing its best to make the mascara run.

I put up the hood of my poncho, thankful it had a little visor.

My feet now felt strange in hiking boots. This head preferred

clogs with higher heels.

What are w·e doing, my head asked, in the back of nowhere,

in a rain forest? I, the head said, would much rather be in a

discotheque or fashionable restaurant enjoying the attention of

a handsome man.

The head kept up a constant stream of grumbling. It was

frightened. We could be attacked by bears or wolves, or, at the

very least, mosquitoes. The head had just arrived from Toronto,

and did not like the Coast at all.

Although I had shed my original head, I still had its con

tents. I could remember what it had known, but from a distance,

disembodied, as if someone else were telling me. And the part

of me which remembered what was in my old head did not like

my new head. What I had now were the contents of two heads,

and I_ had to keep them from arguing. The old head had no to

lerance for the new head's homesickness for "Trawna", and her

'

Room of One's Own - 4

glorification of that place, to the detriment of the Coast.

In spite of the head's attractiveness, vacuous though it was,

I would only bear it for an hour, and when I came upon another

head, I thankfully pushed back the hood of my poncho and

unscrewed the "Trawna" head. My hands were slippery because

of the wet and I fumbled , unfortunately dropping the head in

the mud.

The next head was that of a grizzled old man of the Nootka

tribe and I snapped it on with an instant feeling of relief, for he

so suited the Trail. We set out briskly, our long strides contrast

ing with the mincing ones of the previous head, but my legs

began to ache and I begged him to slow down. He refused, ob

durately, silently, and loped along, climbing steep hills at such a

pace, my body panted and sweated.

Then we came to a ravine which was seventy feet deep and

nearly as wide. The sides were steep and the bottom rocky. My

old head would have turned around there, but my Indian head

only looked at the great fallen tree which was the bridge and

without hesitation guided my feet across it.

Eventually we turned down to the beach for some lunch.

I thanked him heartily until I discovered we were not to relax

with a dehydrated meal from our pack. He directed me to col

lect two dozen of the giant blue mussels which clung to the

rocks in clusters among barnacles as big as calcified eyeballs. We

smashed the shells with a rock, dug out the slimy mussels and

popped them in our mouth. They tasted delicious- strong and

salty- until they were halfway down our gullet. Then my

stomach rebelled and I vomited, much to the displeasure of our

head, who set off back to the Trail, as if to get away from me.

The head was in a hurry to reach Tofino. His brother-in-law

had borrowed his fishing boat and, after two cases of beer,

rammed it into a log boom. The head continually muttered

about what he was going to do to the no-good-son-of-a-bitch

when he caught up with him. Still, he was an improvement over

the Toronto head, at least on the West Coast Trail. He was im

pervious to the weather and I did not need to put my hood up.

I enjoyed the rain mingling with the sweat on his forehead.

I would have stuck with him all the way to Bamfield, so

well did he fit the environment, had we not scrambled down a hill

and come into a little clearing with a rock in the n1iddle. The

Room of One's Own - 5

rock was completely bare, even of the usual moss and lichen,

which do their best to claim all protruberances in this climate.

On the rock was another head. The Indian wanted me to kick

it out of the way and pass on, but I stopped.

Barbara Masterful Jacobsen.

This was the ultimate head, the apotheosis, the very pinnacle

of the heap of heads. It was blonde and beautiful with a maturity

lacking in the Toronto head, health and wisdom glowing from

its unusual violet eyes. The hair was drawn back into a chignon

which accentuated the firm chin and well-formed nose. Even

the lines beginning faintly around the eyes and mouth added

character. It was as if someone had taken a perfect piece of

wood or marble and skilfully freed the personality within. This

head suited every environment. I would be proud to continue in

solitude with it or wear it to an Art Gallery, school concert,

supermarket, or business meeting. It \Vould be comfortable any

where. It was indeed the sort of head I would have chosen for

myself.

Barbara Masterpiece Jacobsen.

The Indian head did not want to come off, and in a way I

was loathe to trade. But he was not so versatile as the blonde. I

unscrewed him and carefully set him on the rock in exchange.

He glared at me; I remembered his errand ; my new head and I

felt a conscience. I stuck him in my pack. The least we could do

was convey him to Bamfield.

The new head and I had so much to talk about we paid little

attention to the Trail, hopping over rocks, up and down cliffs,

glimpsing the ocean, crossing more creeks on fallen logs. We felt

a minimum of effort and fatigue. The minute we joined forces

the sun shone with perfect warmth, making the forest glisten

with rich greens and yellows, drying pubbles so our way was

smoothed.

The head was most agreeable and nurturing. I felt in awe of

her wisdom, clear vision, and subtle wit. She was the perfect

adult, the one for whom I'd searched since childhood. In a way,

her nurturing attitude made me feel a child again, yet a child

treated as ~n equal, full of promise for attaining the same wisdom.

I admired the head's fulfilment, specifically her motherli

ness. For although my old head and I had been a mother for

more than a decade, we had never felt like one. This head wore

'

Room of One's Own - 6

maternity like a halo, yet she also wore sexuality and friendship.

She had, I discovered, a Ph.D. in the humanities. She could

have sought a doctorate in no more appropriate area. Yet she

was well-versed in scientific and political topics, as well as the

origins of language, black holes, and googles, and whether

Margaret Trudeau was pregnant. When discussing recipes, she

did not talk about tomato-beef casserole; but creole, not potato

soup, but vichyssoise. To every topic she brought a creative

ability to see the issue burning through the verbal smoke.

I could have walked forever, so delighted was I with my new

head- no, I wished to camp. There could be no better companion

with whom to share a quiet fire. And it seemed, although per

haps I flatter my imperfect body, that she was also pleased with

me. Even when not conversing we tingled with the excitement

of communion. She understood me better than I did myself,

yet gave me hope that one day I might understand her as well.

The head and I would share my body; would, 1 scarely

dared to breathe, continue as a person. Leave the mysteries of

the West Coast Trail and return to the city as one.

Barbara Madonna Jacobsen.

This was God incarnate; God in carnal form.

The sun shone by day, the moon, forever full, lit our night.

The elements knew this head in the same way the one bright

star had known the birth of Jesus. And so the Trail became

more than a Life-Saving Trail; it became a Life-Giving Trail. As

we talked, she infused my past with newness, mingling her wis

dom with my juices. And she was dependent on me to nourish

her, so we became patron and artist, each giving equally to the

other.

Heads need bodies to survive. They cannot eat unless there

is a place for the food to go. As I fed my new head I remembered

the Indian, who, by virtue of my not having left him on the

rock, was also my responsibility. I stuck him on top of my per

fect head and fed him as well.

Then what conversations we had. He gave to my wise ma

donna head the knowledge of the land. I spread my body out

and felt it joining to the earth, felt my fingers stretching around

the trees, and my blood mingling with the sap and rain . We all

grew into one and the pounding of the ocean surf became our

heartbeats.

Roorn of One's Own - 7

We stayed many days between the Trail and the sea, growing

steadily deeper into the land. We had no need of others. Be

tween us there existed harmony and completion. The Indian

procured the food, the Madonna directed its preparation and

my body cooked and ate it. And all this time it never rained.

Yet the sun's warmth was so gentle it did not destroy the forest

with a drought, but allowed the dew to moisten the moss and

trees so they could continue in their green fecundity.

We ate what the land and sea provided, dressed in their

clothes, slept within the earth. The Indian forgot his boat,

Madonna forgot her Ph.D. and I forgot my family a~d cobwebs.

We lived in quiet, contented excitement until my old head

found us.

Barbara Menacing Jacobsen.

She was perched on the shoulder of a man in a jogging suit,

who, judging by his speed, was determined to break all records

on the Life-Destroying Trail. The trees swayed and the clouds

gathered, and we three knew a splitting of our personality. The

man had not relinquished his own head, but had added mine to

the side. Either head spoke as saw fit, unlike us, who only spoke

with the Madonna's mouth.

I looked at my old head through all our eyes and felt com

passion and sadness. She did not belong. She was anxious,

harried, incomplete. With every impatient incessant movement

of the man's body she had to shrug to maintain her purchase of

his shoulder. He did not want her; we did not want her. I recog

nized her only from the denizens of my very old mind, from a

tingling in my gut, a tightening of my muscles.

Madonna frowned. The Indian was silent and severe.

"You have to take it," the man said. "You can't leave it

lying around."

The Indian shook his head. "We don't need any more.

There's not enough room, see?"

"You could put her on top," Madonna said dubiously.

"Goddammit!" old head shouted. "There's things to do! I

have children. A husband. A mother. Cobwebs to clean. I must

get back. And in my own body!"

She made the man pick up a stone. He bashed the Indian.

He stru_ck _Madonna. M):' old_ head hung on his shoulder laughing

and shr1ek1ng and swearing hke the mad distorted thing she was.

Room of One's Own - 8