Table Of Content1

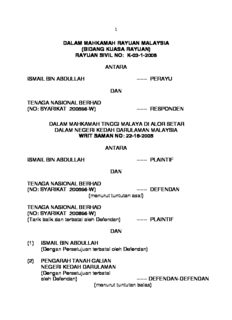

DALAM MAHKAMAH RAYUAN MALAYSIA

(BIDANG KUASA RAYUAN)

RAYUAN SIVIL NO: K-03-1-2008

ANTARA

ISMAIL BIN ABDULLAH ------ PERAYU

DAN

TENAGA NASIONAL BERHAD

(NO: SYARIKAT 200866-W) ------ RESPONDEN

DALAM MAHKAMAH TINGGI MALAYA DI ALOR SETAR

DALAM NEGERI KEDAH DARULAMAN MALAYSIA

WRIT SAMAN NO: 22-16-2005

ANTARA

ISMAIL BIN ABDULLAH ------ PLAINTIF

DAN

TENAGA NASIONAL BERHAD

(NO: SYARIKAT 200866-W) ------ DEFENDAN

(menurut tuntutan asal)

TENAGA NASIONAL BERHAD

(NO: SYARIKAT 200866-W)

(Tarik balik dan terbatal oleh Defendan) ------ PLAINTIF

DAN

(1) ISMAIL BIN ABDULLAH

(Dengan Persetujuan terbatal oleh Defendan)

(2) PENGARAH TANAH GALIAN

NEGERI KEDAH DARULAMAN

(Dengan Persetujuan terbatal

oleh Defendan) ------ DEFENDAN-DEFENDAN

(menurut tuntutan balas)

2

DAN

PENGARAH TANAH GALIAN

NEGERI KEDAH DARULAMAN ----- PIHAK KETIGA PERTAMA

DAN

PENTADBIR TANAH

DAERAH PENDANG ----- PIHAK KETIGA KEDUA

(menurut prosiding pihak ketiga)

CORAM:

(1) ABDUL MALIK BIN ISHAK, JCA

(2) K N SEGARA, JCA

(3) ABDUL WAHAB PATAIL, JCA

ABDUL MALIK BIN ISHAK, JCA

DELIVERING THE JUDGMENT OF THE COURT

Introduction

[1] After having filed his writ and his statement of claim, the

appellant (Ismail bin Abdullah) applied for summary judgment against the

respondent (Tenaga Nasional Berhad) under Order 14 of the Rules of the

High Court 1980 (“RHC”). On 27.11.2006, the deputy registrar allowed

the appellant’s summary judgment application.

[2] Aggrieved by the decision of the deputy registrar, the

respondent filed an appeal to the High Court. On 10.12.2007, the learned

Judicial Commissioner (“JC”) allowed the respondent’s appeal. It is

3

against the decision of the learned JC in respect to the Order 14 matter

that the appellant appeals to this court.

[3] However, on 19.12.2006, the respondent filed an application to

amend its statement of defence in enclosure 46 after the deputy registrar

had allowed the appellant’s summary judgment application.

[4] On 22.2.2007, the application to amend the respondent’s

statement of defence in enclosure 46 came up for hearing before the

senior assistant registrar (“SAR”). On 12.3.2007, the SAR dismissed

enclosure 46.

[5] The respondent then appealed to the High Court and, on

6.11.2007, the learned JC allowed the respondent’s application to

amend the statement of defence with costs without first hearing the

respondent’s appeal against the order granting summary judgment.

The background facts

[6] Sometime in 1995, the respondent commenced the “wayleave”

procedures under section 11(1) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 against

certain portions of lands in Kota Setar, Kuala Muda, Pendang and Kubang

Pasu districts in Kedah for purposes of constructing the electricity supply

lines from Gurun to the border (Malaysia/Thailand).

[7] Two portions of the appellant’s lands in Pendang were affected.

The first was at Lot 1026 involving 1.442 acres. The second would be Lot

4

2062 involving 0.820 acres. To achieve its desired purposes, the

respondent issued the requisite notices under section 11(2) of the

Electricity Supply Act 1990.

[8] The appellant as the land owner objected to the “wayleave”

exercise in so far as his lands in Pendang were concerned. An enquiry

under section 11(6) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 was then conducted

by the District Land Administrator (hereinafter referred to as the “DLA”).

By virtue of section 11(7) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990, the DLA

authorised the proposed utilisation of the appellant’s portions of the lands

by the respondent and the DLA also ordered the respondent pursuant to

section 16(1) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 to pay the appellant

compensation in the sums of RM10,124.00 and RM15,310.00 respectively

for both portions of the lands respectively.

[9] The appellant appealed against the compensation sums ordered

by the DLA to the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri Kedah (hereinafter

referred to as “MMK”) pursuant to section 16(2) of the Electricity Supply

Act 1990.

[10] The MMK acting as the State Authority under sections 11(7)

and 16(2) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 decided in favour of the

appellant and varied the order of the DLA by requiring the respondent to

pay the appellant the sums of RM247,808.00 and RM557,108.00

5

respectively for the two lots totalling RM804,916.00 as compensation and

this information was conveyed through the Pengarah Tanah dan Galian’s

(PTG’s) letter dated 28.9.2005 (see pages 501 to 503 of the appeal record

at Jilid 3).

[11] The respondent refused to pay the sum of RM804,916.00 to

the appellant in spite of the notice of demand dated 19.11.2004. The

appellant had no choice but to file his writ and his statement of claim

seeking for the sum of RM804,916.00 from the respondent. The appellant

succeeded in his Order 14 application before the deputy registrar but was

unsuccessful before the learned JC pursuant to an appeal by the

respondent. Hence, the present appeal before us.

Analysis

[12] In a summary judgment proceeding, the defendant is required

to satisfy the court under Order 14 rule 3(1) of the RHC that there is an

issue or question in dispute which ought to be tried or that there ought “for

some other reason to be a trial.”

[13] The Supreme Court decision in Bank Negara Malaysia v

Mohd Ismail & Ors [1992] 1 MLJ 400 is the leading authority on an Order

14 application. Mohamed Azmi SCJ, writing for the majority, had this to

say at page 408 of the report:

“In our view, basic to the application of all those legal propositions,

is the requirement under O 14 for the court to be satisfied on affidavit

6

evidence that the defence has not only raised an issue but also that

the said issue is triable. The determination of whether an issue is or

is not triable must necessarily depend on the facts or the law arising

from each case as disclosed in the affidavit evidence before the

court.”

[14] Continuing on the same page, his Lordship Mohamed Azmi

SCJ said:

“Thus, apart from identifying the issues of fact or law, the court must

go one step further and determine whether they are triable. This

principle is sometimes expressed by the statement that a complete

defence need not be shown. The defence set up need only show that

there is a triable issue.”

[15] Finally, towards the end of the same page, his Lordship

Mohamed Azmi SCJ aptly said:

“Where the issue raised is solely a question of law without reference

to any facts or where the facts are clear and undisputed, the court

should exercise its duty under O 14. If the legal point is understood

and the court is satisfied that it is unarguable, the court is not

prevented from granting a summary judgment merely because ‘the

question of law is at first blush of some complexity and therefore

takes a little longer to understand’. ”

[16] Where the defendant’s defence is unsustainable in law or on

the facts an Order 14 application is an expeditious procedure that would

enable the plaintiff to dispose of an action and is the best method of saving

time and costs. A full blown trial, unnecessary in such circumstances, is

avoided. But where there are triable issues, summary judgment would not

be an appropriate alternative (Mayban Finance Bhd v. Wong Gieng Suk

& Anor [2003] 1 CLJ 27).

7

[17] Roskill LJ in Verrall v. Great Yarmouth Borough Council

[1981] QB 202, 218, CA, aptly said:

“We have often said in this court in recent years that where there is a

clear-cut issue raised in Order 14 proceedings, there is no reason

why the judge in chambers–or, for that matter, this court–should not

deal with the whole matter at once. Merely to order a trial so that the

matters can be re-argued in open court is to encourage the law’s

delays which in this court we are always trying to prevent. The first

point fails.”

[18] Robert Goff LJ in European Asian Bank A.G. v. Punjab &

Sind Bank (No. 2) [1983] 1 WLR 642, 654, CA, made the following

germane observations:

“Moreover, at least since Cow v. Casey [1949] 1 K.B. 474, this court

has made it plain that it will not hesitate, in an appropriate case, to

decide questions of law under R.S.C., Ord. 14, even if the question of

law is at first blush of some complexity and therefore takes ‘ a little

longer to understand.’ It may offend against the ‘whole purpose of

Order 14 not to decide a case which raises a clear-cut issue, when

full argument has been addressed to the court, and the only result of

not deciding it will be that the case will go for trial and the argument

will be rehearsed all over again before a judge, with the possibility of

yet another appeal; see Verrall v. Great Yarmouth Borough Council

[1981] Q.B. 202, 215, 218, per Lord Denning M.R. and Roskill L.J.

The policy of Order 14 is to prevent delay in cases where there is no

defence; and this policy is, if anything, reinforced in a case such as

the present, concerned as it is with a claim by a negotiating bank

under a letter of credit: compare Bank fur Gemeinwirtschaft

Aktiengesellschaft v. City of London Garages Ltd. [1971] 1 W.L.R.

149, 158, per Cairns L.J., a case concerned with a claim on a bill of

exchange by a holder in due course.”

[19] Thus, where an issue raised in an Order 14 application is one

of law and is clear-cut, it should be disposed off forthwith instead of going

to trial.

8

[20] And this is the right approach to adopt notwithstanding that,

“The effect of Order 14 is to shut the defendant from having his day in

the witness box. It is a very special jurisdiction and is only to be

invoked in cases where there is no bona fide triable issue” (per Gopal

Sri Ram JCA (later FCJ) in Ng Hee Thoong & Anor v Public Bank Bhd

[1995] 1 MLJ 281, at page 287).

[21] If the point of law is clear and the court is satisfied that it is

really unarguable, then leave to defend will be refused (Israel Discount

Bank of New York v. Hadjipateras And Another [1984] 1 WLR 137, at

145, CA; [1983] 3 All ER 129, at 135, C.A.). And where the words of the

statute under which the action was brought clearly made the defendants

liable, the court in Nassau Steam Press v. Tyler And Others [1894] 70

L.T. 376 refused to give leave to defend.

[22] Now, this appeal brings into sharp focus the rigours of the

Electricity Supply Act 1990 and, in particular, section 16(2) of the same Act

which enacts as follows:

“Compensation

16. (2) Any person aggrieved with the District Land Administrator’s

assessment may within twenty-one days after the assessment appeal

to the State Authority whose decision shall be final.”

[23] It means what it says. Precisely put: the decision of the State

Authority – referring to MMK, shall be final. And in refusing to settle the

9

sum of RM804,916.00 awarded by MMK, the appellant’s remedy was

rather simple. It was to file this suit for recovery and that the respondent

therefore had no legal defence to the suit but must pay the sum awarded. It

is as simple as that.

[24] A mandatory interpretation must be accorded to the word

“shall” that appears in section 16(2) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990.

[25] The House of Lords in Re Racal Communications Ltd [1980]

2 All ER 634 dealt with section 441(3) of the Companies Act 1948 which

provides, so far as is material, that the decision of a High Court judge on an

application under section 441 for an order authorising the inspection of the

company’s books or papers where it is shown that there is reasonable

cause to believe that an officer of the company has committed an offence

in connection with the management of the company’s affairs and that

evidence thereof is to be found in the company’s books or papers “shall

not be appealable”, means, according to the House of Lords, what it says,

and there is no justification for the view that its operation is restricted to

questions of fact so as to give the Court of Appeal jurisdiction to hear an

appeal from the decision of the judge on a question of law. The House of

Lords also held that in any event, since the jurisdiction of the Court of

Appeal is wholly statutory and appellate only and since it has no original

jurisdiction, the effect of section 31(1)(d) of the Supreme Court of

10

Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925, which provides that no appeal shall lie

from the decision of the High Court or any judge thereof where it is

provided by any Act that the decision of any court or judge the jurisdiction

of which or of whom is vested in the High Court is to be final, is to deny the

Court of Appeal all jurisdiction in connection with such decision whether

they relate to issues of fact or of law. Lord Salmon writing a separate

judgment for the House of Lords had this to say at page 640 of the report:

“I am not at all surprised that s 441(3) laid down that ‘The decision of

a judge of the High Court ..... on an application under this section

shall not be appealable’. After all, s 441(1) was making available

exceptional powers to the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Board

of Trade and chief officers of police providing that the High Court

judge was satisfied that there was reasonable cause for the exercise

of those powers. If he was not so satisfied and refused the

application, Parliament, in my respectful view, rightly considered

that that should be an end of the matter and that therefore there

should be no appeal.”

[26] Lord Edmund-Davies, also writing a separate judgment for the

House of Lords in Re Racal Communications Ltd (supra) observed at

page 641 of the report:

“My Lords, the determining issue in this appeal relates to the

jurisdiction of the Court of Appeal to entertain an appeal against the

decision of a High Court judge in a matter declared by statute to be

not appealable.”

[27] Continuing at page 645, Lord Edmund-Davies aptly said:

“But, since the words of ouster in s 441(3) barred an appeal to the

Court of Appeal, they had no jurisdiction to consider the matter at

all.”

Description:By virtue of section 11(7) of the Electricity Supply Act 1990, the DLA authorised [73] In B. Surinder Singh Kanda (supra), the court there held that.