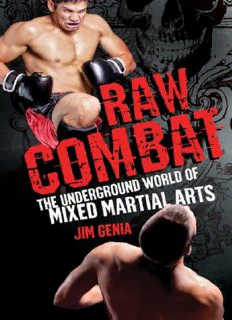

Table Of ContentRAW COMBAT THE UNDERGRGOUND WORLD

OF MlXED MARTlAL ARTS

JIM GENIA

CITADEL PRESS

Kensington Publishing Corp.

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

This book is dedicated to Gaby and Emmy,

my perfect wife and my perfect daughter.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

TRADITION

NEW YORK

PETER

A TALE OF TWO FIGHT SHOWS

TSK

TAP OUT

LYMAN

JAMES

KIMBO

SUBMISSION ATTEMPTS

BAMA FIGHT NIGHT

EPILOGUE

Copyright Page

T

Acknowledgments hanks to Farley and Richard, an agent and

an editor who believed. Thanks to Dale Peck, Peter Carey, and

Roger MacBride Allen, three writing instructors who bade me to

not suck. And a very special thanks to everyone who’s ever

stepped into the ring or cage and fought, bled, won, and lost. The

word inspiration doesn’t quite describe it, but it comes close.

TRADITION

I

paid thirty bucks to the big, burly man at the door and walked into the

South Bronx boxing gym unsure what to expect. It was February of 2003 and I

was playing the role of curious spectator, my hidden notepad and pen and digital

camera the only indicators otherwise. Around me sat a few dozen in bleachers,

some of them cheering, all of us transfixed by the ring in the center of the room

and the occupants within. And when the judo black belt in traditional kimono

had his arm suddenly and violently twisted and broken by the kickboxer clad

only in Lycra shorts, that was it. The New York underground fight scene had me

hooked. It was beautiful, a poetry of violence, calligraphy with karate for

brushstrokes and jiu-jitsu for ink.

Seven years and close to thirty editions of something called the Underground

Combat League, watching hundreds of men throw everything they had at each

other, and from the start I knew was gazing upon something special. If you live

in the Five Boroughs, the UCL is the only game in town, the only place to see a

Five Animal-style kung fu instructor get clobbered by someone who knows how

to fight for real, the only place to see a personal trainer from the David Barton

Gym on his hands and knees, blood leaking from his forehead and mouth and

dotting the canvas. The UCL, not the first but for sure the most resilient, what

you’d get if you made Fight Club a sport (but don’t ever call it “Fight Club”;

doing that shows how much you don’t really know) and gave the thing a life of

its own, made it a magnet for thugs looking to pound someone, for aspiring

fighters and wannabes, for the ignorant and disillusioned, for the psychotic. A

tradition, like when they’d gather in dojos in post-feudal Japan and scrap, or

when they’d meet in back alleys in Brazil or under tents at fairgrounds in

Europe, only a modern, up-to-date version where the party crashers wear blue

uniforms and carry Glocks. A tradition, practically a Big Apple institution, and

when mixed martial arts is legalized there will be no more need for it.

Puchy the bouncer (left) taking on a Five Animal kung fu instructor. (Jim Genia)

On a Sunday night I’m there, at the edge of a boxing ring somewhere in the

Outer Boroughs. An endless array of cheap multicolored event posters cover the

walls, warped and pitted floorboards squeak with each footfall, and the faded

blue Everlast canvas stinks like meat gone spoiled, a side of beef long on dried

blood and tetanus. Close by is a diminutive 135-pound Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black

belt named Emerson, there in the ring, so close I could reach out and touch him.

He’s an instructor, and his students present number over a hundred, a hundred

and they’ve vacated the bleachers to crowd around the ring, a mad rush in the

seconds before combat. If anyone is cheering for the karate fighter from Harlem,

it’s lost, whispers amidst crashing ocean waves. The referee yells “Go!” In the

span of thirty-six seconds the Brazilian takes his opponent down, straddles him,

and rains down punches until the karateka taps the canvas with his hand

indicating “No mas, no mas!” It’s all over but for the mayhem of celebration,

and the tableau is so stunning, so charged and evocative, it could be a

Caravaggio hanging in the Louvre.

Vale tudo, they had called it in Brazil in the 1900s (Portuguese for “anything

goes”), but by the end of the century it was called something else here in the

States, sometimes Ultimate Fighting or, disparagingly, human cockfighting, and

now mixed martial arts (MMA) since the outrage over the spectacle has faded.

The entire world went nuts over a SpikeTV reality show involving aspiring

fighters battling it out in a cage called the Octagon, a more palatable thrill easier

to swallow, and it’s legal to hold such matches in Nevada, California, New

Jersey—legal almost everywhere but New York. And I’m here thanks to a

clandestine text message revealing time and place, clandestine because the New

York State Athletic Commission isn’t too keen on these sorts of shindigs.

The karateka and the Brazilian shake hands and hug, according each other all

sorts of respect and gratitude. The vanquished is as much a victim of the

Brazilian’s technique as of his own outdated training methodologies (punching

and kicking imaginary opponents usually gets you a big fistful of fail), and he’ll

never step into the ring unprepared again. But it isn’t about who wins or who

loses as much as it’s about the intensity of the battle, and this one has provided

all with an up-close and hugely satisfying dose of it. In Las Vegas, superstars

like Brock Lesnar and Randy Couture are captivating millions from within the

cage of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, but here, at the lowest levels and in

the trenches, the frontline skirmishes are all about local heroes giving it

everything they’ve got and giving fans of fighting a glimpse of the reality of

mano a mano combat.

Peter Storm is the man behind it all. Some say he’s a villain, his secret events

in ghetto-tastic boxing gyms deservedly criminal. But he’s just someone you

eventually stumble across if you live in the Big Apple and tote around a love for

all things fighting. In the fourteen years since the first UFC graced the pay-per-

view airwaves, promoter wannabes have sunk millions into organizations that

crashed and burned and failed in spectacular fashion, but Peter took aim at a

target more attainable, aimed square at the demographic hungry for intimate and

personal action and an atmosphere of “Holy crap, these are some badass

underground fights!” A feint, a body blow, and then a bare-knuckle hook to the

chin and he’s scored a knockout.

“We’ve never had a problem with the athletic commission or the police,” he

tells me, alluding to more of a “catch me if you can” than a “go ahead, try to shut

me down, mother-fucker” way of thinking. For Peter has never and would never

advertise. You’re either on his list to get a text message or you’re not—and if

not, the only way you’ll ever know there was a UCL event last weekend is if

your friend fought or maybe, just maybe, you scour the Internet for MMA-

dedicated news sites and find results. It’s the Keyser Soze of fight shows.

Peter (right) taking on a street fighter. (Jim Genia)

At mixed martial arts events in states where sanctioning is a way of life,

where an athletic commission official oversees the urine samples for drug

screening and someone with a conscience—or at least a concern about tort law—

has matched up the competitors, the fighters will be more or less athletes of

near-equal degrees of skill and commitment. But at an underground show

anything goes and there are no weight classes. So if you agree to face someone

with a hundred pounds on you, well, more power to you, brother.

Who are these people willing to risk their health and wellbeing in the

unsanctioned wilds of unarmed combat? At a New York City underground show,

words like motley crew, varied assortment, and wretched hive of scum and

villainy barely scratch the surface.

On one Sunday afternoon in June, at a martial arts school in Midtown, the cast

of characters includes a massive Puerto Rican judoka, a lithe black boxer from

Gleason’s Gym, a short kickboxer from Jackson Heights, and a scrawny Tae

Kwon Do practitioner. This UCL installment doesn’t have the benefit of a

boxing ring, so the forty-five or so spectators sit in white molded-plastic chairs

around a large blue mat scarred with what could be a century of use. Peter, the

maestro in the judo uniform, roams the room while his right-hand man, an

amiable Hispanic named Jerry, talks of the task of rounding up competitors. If

Peter is the bad cop in the equation, Jerry is the nice one who offers you coffee

and hears your confession.

“The fighters who normally compete at these shows already know about

mixed martial arts and most of the time they contact us because they want to

fight,” Jerry says. “Certain traditionalists are the ones that I find it hard to

explain it to, because a lot of them have unrealistic thoughts of fighting,” he

says, alluding to every karate or kung fu practitioner rigid in their beliefs that all

that’s needed to win lies within one esoteric and outdated martial style.

“To be honest,” Peter interjects, “we find a lot of guys who just want to fight.”

Or, more accurately, those guys find him.

Most aspiring combatants know how to find Peter. When not working

nightclub security, he teaches private lessons at a school in Manhattan called the

Fighthouse that rents out space to a wide variety of martial arts instructors, a

repository of senseis without dojos of their own. It’s a point of convergence for

almost everyone who’s ever donned a gi, slipped on padded gloves, and stuck a

battered Bruce Lee′s Fighting Method into their knapsack. If you’re interested in

MMA in the Five Boroughs, one way or another, your path will lead you to him.

Today’s match-ups would seem set to answer the age-old question of “Which

style is best?” and Jerry informs me they’re waiting on a fighter named Manny

to arrive, Manny the ace in the hole, Manny the supposedly baddest man on the

roster. In the meantime, the boxer from Gleason’s Gym takes on the kickboxer

from Jackson Heights, a fisticuff that deteriorates into something resembling a

mugging, ending only when the boxer lands a right cross that drops his

opponent, the boxer refraining from taking his foe’s wallet and instead breathing

a deep sigh of relief. The massive Puerto Rican, nervous and sweaty and a

nightclub security worker himself, is up next, and he needs just a minute and a

half to hyperextend his opponent’s arm and force capitulation. Someone in the

crowd shouts, “Break his fucking arm!” but that never comes to pass. (The

Puerto Rican tells me his lady gave birth the night before and he got no sleep.)

There’s a lull in the action and I’m informed that they’re still waiting on

Manny, Manny the heretofore unheard of Hercules and Gilgamesh of New York.

Meanwhile, the scrawny Tae Kwon Do fighter squares off against someone

called Iron Will, Iron Will shirtless and possibly even scrawnier than his

opponent, like the “after” photo of someone who spent a few years on meth. The

audience is subjected to frantic images of a cartoonesque melee, with all the

chaos and flying limbs, and the Tae Kwon Do man goes down from a kick to the

groin. There are only four rules of engagement in this league, practical

restrictions labeled as “gentlemanly,” and they are: no biting, no eye-gouging, no

fish-hooking, and no groin strikes. The bout is ruled a “no contest,” although

things could’ve played out much differently if these underground fighters had

deigned to wear cups.

Description:A unique look into a side of MMA that only a few know and only Genia can give. 'Chris Palmquist, partner, MixedMartialArts.com Out Freakin' ColdForget pay-per-view. Forget championship belts or sanctioning bodies. This is Mixed Martial Arts combat in its purest, rawest form. Follow Jim Genia into th