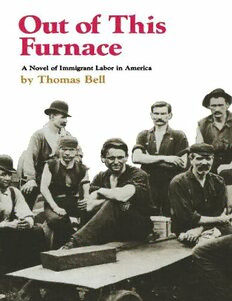

Table Of ContentOUT OF THIS FURNACE

BY THOMAS BELL

With an Afterword by David P. Demarest, Jr.

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PRESS

Pittsburgh and London

Copyright © 1976, University of Pittsburgh Press

Copyright 1941 by Thomas Bell

Copyright © renewed 1968 by Marie Bell

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

20 19 18

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-6657

ISBN 0-8229-5273-4

A CIP record is available from the British Library.

TEXTUAL NOTE

Out of This Furnace was originally published in 1941 by Little, Brown and Company, then reissued by

the Liberty Book Club, Inc., in 1950.

Minor textual changes were made in the 1950 edition, and it is not clear whether these alterations were

initiated by the author or the second publisher. This new edition duplicates the original version.

ISBN 978-0-8229-7886-2 (electronic)

To the Memory

of

my mother, my father and my grandfather

CONTENTS

Author's Note

Part One, Kracha

Part Two, Mike Dobrejcak

Part Three, Mary

Part Four, Dobie

Afterword

Acknowledgments

AUTHOR'S NOTE

This book is a novel, fiction, and—allowing for the obvious exceptions—the

proper names used in it do not refer to actual persons who may bear the same or

similar names.

With that said, this much more may be: I have been as true to the events, the

people and the place as lay within my power.

Part One

KRACHA

1

GEORGE KRACHA came to America in the fall of 1881, by way of Budapest

and Bremen. He left behind him in a Hungarian village a young wife, a sister

and a widowed mother; it may be that he hoped he was likewise leaving behind

the endless poverty and oppression which were the birthrights of a Slovak

peasant in Franz Josef's empire. He was bound for the hard-coal country of

northeastern Pennsylvania, where his brother-in-law had a job on a railroad

section gang.

A final letter from America had contained precise instructions. Once landed in

New York he was to ask his way to the New Jersey ferry and there buy a railroad

ticket to Pennsylvania. It was likely that aboard ship he would meet Slovaks who

were going his way or were being met in New York by relatives; their help

should be his for the asking. If not, he was to ask his way by showing to any

policeman the enclosed paper, on which was written in English: Andrej Sedlar,

Lehigh Railroad, White Haven, Pa. He was to beware of strangers who tried to

get friendly with him on the street, and under no circumstances should he permit

anyone to handle his money.

The warnings had not been entirely necessary. Kracha knew as well as the

next man those dismal tales which had drifted back to the old country—about

trusting immigrants robbed and beaten their first day in America, about others

who stepped off the ship and were never seen again, about husbands found in

alleys with their throats cut from ear to ear while their brides of a month

vanished forever into houses of prostitution. Determined that no comparable

calamities should befall him, he had set out prepared to assault the first stranger

who so much as bade him good day.

Unfortunately no one had thought to warn him against his own taste for

whisky and against dark women who became nineteen years of age in the middle

of the ocean.

He had first noticed Zuska on the pier at Bremen. Later, aboard ship, he met

her and John Mihula, her husband; in the crowded steerage that took no

planning. They were Slovaks from Zemplinska, the province to the northeast of

Kracha's own Abavuska, and they were going to Pittsburgh, where Zuska had a

married sister. Mihula was several years older than Kracha, a pleasant, quiet

young man with delicately pink cheeks and blond, wavy hair. There was nothing

else noteworthy about him except, possibly, his possession of a woman like

Zuska.

She was as dark as her husband was fair, as lively as he was grave, a dark-

skinned, compactly plump girl who missed beauty, even prettiness, by a face too

broad at the cheekbones and a nose that matched. She lacked beauty, but had no

need of it; the day after she boarded the ship every man on it was as keenly

aware of her as if she had come among them naked. She had a throaty laugh, a

provocative roll to her hips and she could warm a man to the roots of his hair

with a look.

Long before the voyage ended—it lasted twelve days—Kracha had convinced

himself that Zuska was a deeply passionate woman unluckily married to a

husband whose abilities were hopelessly unequal to her needs. His pity for her

was as profound as his own sense of frustration; in the congestion of the steerage

the privacy necessary for such condolences as he felt like expressing was

unthinkable.

A week or so out of Bremen, however, Zuska revealed that the day was her

birthday, her nineteenth, and stirred by no clearly defined impulse Kracha

bargained with a steward for two quarts of whisky and German wine in a long-

necked bottle. His appearance, laden, was a triumph. The inescapable accordion

player was summoned, the bottles opened, and they had a little party. They

drank, danced and sang. Kracha undertook to explain why, among people who

were not from Zemplinska, Mihula's way of saying he had just risen would be

sure to arouse ribald laughter. He did not convince Mihula, who no more than

anyone else could tolerate being told how to speak his own language, but Zuska

glanced at Kracha and laughed. Encouraged, he pretended to be drunker than he

was and took liberties with her person which she repulsed with surprising

ferocity but without changing his opinion of her.

And that was why Kracha, who had left home with enough money to carry