Table Of ContentMirror Affect

This page intentionally left blank

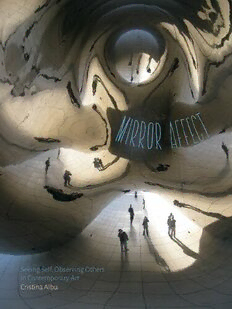

Mirror Af fect

Seeing Self, Observing Others in Contemporary Art

Cristina Albu

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

London

Copyright 2016 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy-

ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper

The University of Minnesota is an equal- opportunity educator and employer.

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Albu, Cristina, author.

Title: Mirror affect : seeing self, observing others in contemporary art / Cristina Albu.

Description: Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references

and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016003060 (print) | LCCN 2016005798 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-5179-0005-2 (hc) |

ISBN 978-1-5179-0006-9 (pb) | ISBN 978-1-4529-5259-8 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Visual perception in art. | Reflection (Optics) in art. | Art, Modern—20th century—

Themes, motives. | Art, Modern—21st century—Themes, motives.

Classification: LCC N7430.5.A33 2016 (print) | LCC N7430.5 (ebook) | DDC 701/.18—dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016003060

Contents

Introduction: Seeing Ourselves Seeing 1

1 Mirror Frames: Spectators in the Spotlight 31

2 Mirror Screens: Wary Observers under the Radar 109

3 Mirror Intervals: Prolonged Encounters with Others 155

4 Mirror Portals: Unpredictable Connectivity

in Responsive Environments 203

Conclusion: Networked Spectatorship 251

Acknowledgments 263

Notes 269

Index 293

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction

Seeing Ourselves Seeing

The diverting of attention from that which is meant to compel it,

i.e., the actual work on display, can at times free up a recognition

that other manifestations are taking place that are often difficult

to read, and which may be as significant as the designated objects

on display.

— Irit Rogoff, “Looking Away: Participations in Visual Culture”

As we walk through art museums and galleries, more and more contempo-

rary artworks enhance our awareness of belonging to a shared spectatorial

space. We actively observe not only the objects on display but also our move-

ments and the reactions of other visitors. Artworks that include mirrors, live

video feedback, and sensors frame contexts for seeing ourselves seeing and

acting as part of precarious collectivities. They call our attention to the inter-

personal dimension of perception and invite us to develop affective affilia-

tions toward other visitors concomitantly engaged in mirroring processes as

they discover how their reflections are encompassed in infinity rooms or how

their movements expand the sensory potential of responsive environments.

Under these circumstances, individualistic aesthetic rituals give way to inter-

personal and collective modes of observation and behavior.

What has led artists from the late modernist period onward to challenge

the autonomy of the isolated, self- involved art viewer by highlighting the pub-

lic character of the display context? Do works that stimulate mirroring acts

simply deepen our passive immersion in visual spectacle, or can they actually

1

Introduction

2

disrupt purely contemplative attitudes by cultivating interpersonal aware-

ness and performativity? To what extent can they help us reconsider our posi-

tion and limited degree of freedom in social systems? In this book, I seek to

connect these key questions about reflective and responsive artworks with

current debates on participatory art while tying loose knots among minimal-

ist sculpture, performance art, installation art, and new media. I suggest that

a significant number of contemporary artworks with mirroring properties

enable us to perceive ourselves and others as if from a third distance, inter-

twined in a complex social fabric that alerts us to the critical need for recon-

sidering who we are, how we act, and what consequences our choices have

on others.

Mirror Affect charts the historical trajectories of reflective artworks and

the emergence of increasingly public modes of art spectatorship across mul-

tiple media since the 1960s. My account starts with this decade because it

is marked by an extensive use of materials with mirrorlike properties (e.g.,

Mylar, Plexiglas, stainless steel) and a firm contestation of modernist modes

of art viewing that imply a relation of parallelism between an individual be-

holder and an autonomous art object, shielded from all external influences

that might disrupt the privacy of the aesthetic experience. This idealized

spectatorial relation is not a very long- standing convention, but it is a staple

of the encounter with abstract expressionist and color field paintings, which

situate the viewer in a presumably neutral and secluded plane of optical ab-

sorption. Interestingly, on the occasion of the Abstract Expressionist New York

exhibition of 2011, the Museum of Modern Art was so keen on reifying the

aesthetic experience associated with this stylistic tendency that it asked staff

members to adopt introspective attitudes in front of individual paintings for

a set of photographs meant to accompany the New York Times review of the

show. The documentary photographs were so clearly staged that the news-

paper published a disclaimer a week later, announcing that it found this ap-

proach unethical and explaining that MoMA officials had offered guidelines

for the photo shoot.1

Yet modern art did not imply only introspective modes of engagement.

The futurists organized events that provoked audience members into violent

actions in order to make them abandon their roles as spectators and partici-

Introduction

3

pate in destructive actions that were no longer limited to the space of the

stage. Similarly, the Dadaists were determined to denounce prevailing modes

of spectatorship associated with high culture and take participants in their

events outside their comfort zones. Their events at Cabaret Voltaire were pur-

posefully aggressive toward the audience, as they were meant to disrupt and

destroy social and theatrical norms. Although they were less intent on gen-

erating chaos and destruction than the Dadaists, the surrealists also took an

interest in instigating public reactions through visceral and aggressive im-

agery. Well known are the unruly responses of cinemagoers to Luis Buñuel’s

L’Age d’or (1930) and the voyeuristic experiences envisioned by Salvador Dalí.

Eager to erode both the boundaries between the conscious and the sub-

conscious and the differences between the public and the private, the sur-

realists often conceived modes of art spectatorship that placed the beholder

in the limelight. For the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme of 1938, Marcel

Duchamp came up with the idea of creating a system of lights that would

switch on and illuminate the paintings as visitors approached them, hence

setting the visitors on display along with the artwork. Continuities between

these earlier challenges to aesthetic autonomy and the growing contestation

of introspective modes of spectatorship in the 1960s and 1970s speak to the

complex crisscrossing trajectories of modern and contemporary art, which

defy all attempts to impose neat chronological boundaries.

Recent contemporary artworks that gather large crowds around visual

or interactive interfaces have been increasingly associated with the numb-

ing spectacle of neocapitalism that subordinates individuals and perpetuates

egotistic behavior. Accused of providing fake images of democratic consen-

sus and serving the interests of service economies, they have been pushed

outside the circle of participatory artworks, which take social relations as

their main medium and usually catalyze communal ties based on verbal ex-

changes. Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003), which drew large masses

of visitors to Tate Modern to see themselves seeing while immersed in the

light of a gigantic sun, was both hailed as a sublime landscape showcasing

human vulnerability and condemned as complicit with art museums’ com-

modification of sensory experience. More recently, Marina Abramović’s The

Artist Is Present (2010) performance at MoMA and James Turrell’s Aten Reign