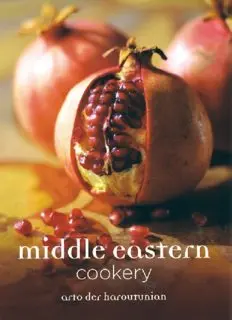

Table Of ContentMiddle Eastern Cookery

Arto der Haroutunian

Grub Street * London Published in 2010 by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.grubstreet.co.uk

Text copyright © Arto der Haroutunian 1982, 2008, 2010

Copyright this edition © Grub Street 2010

Design Lizziebdesign First Published in Great Britain in 1982 by Century

Publishing Co. Ltd A CIP record for this title is available from the British

Library ISBN 978-1-906502-94-2

Digital Edition ISBN 978-1-908117-89-2

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG, Bodmin, Cornwall This book is

printed on FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to all the authors and publishers from whose works I have

quoted (see Bibliography), and apologies to those who unintentionally may have

been overlooked.

All works from Arabic and French have been edited and translated by myself.

I must also thank all the kind people of North Africa who helped in many a small

way in the shaping and writing of this book. Special thanks as well to Odile

Thivillier and Rina Srabonian.

contents

Preface

Introduction

Mezzeh

Churba—soups

Salads

Eggah and kookoo—egg dishes

Pastas, pies and boreks

Kibbehs and kuftas

Yoghurt dishes

Ganachi—cooked vegetables

Dolmas—stuffed vegetables

Pilavs

Kebabs

Fish dishes

Meat dishes

Poultry and game

Firin kebabs and khoreshts

Sauces

Khubz—bread

Torshi—pickles

Desserts and sweet things

Cakes and biscuits

Sweets

Jams and preserves

Ice cream

Khumichk—drinks

Glossary

Bibliography

Footnote

preface

One of the most heartening memories of my childhood is Sunday lunch, when all

the members of our family, as well as guests (mostly young students from the

Middle East), sat around our large table and consumed in delight and with gasps

of rapture the product of my mother’s work. For not only was my mother a

remarkable cook but also, being thousands of miles away from home, we were in

a vast culinary desert devoid of such familiar vegetables as aubergines and okra;

spices such as cumin, sumac and allspice; the honey-soaked, rosewater-scented

desserts of our childhood.

We ate. We argued loudly and vociferously. We drank our thick black coffee and

nibbled a piece of rahat-lokum, a box of which someone or other had just

received from home. Then, thanking the Lord for his bounteous generosity we

settled comfortably into our large, Victorian armchairs and, almost in whispers,

talked of home, of the sun-drenched streets of Aleppo or Baghdad, the rich souks

of Alexandria or the fragrance-inflamed bazaars of Tehran. Someone would then

sing ‘The song of the immigrant’ far away from his village and loved one.

Someone else would hungrily describe how to peel and eat a watermelon—‘You

know, with white goat’s cheese, some warm lavash bread with a sprig of fresh

tarragon tucked nicely in the centre and all washed down with a glass of cool

sous’—all of us lolled in nostalgic euphoria and dreamt of home.

‘Home’ to us all was the Middle East, not the political entity of today with its

strong regional, national and social differences. In those days (the late forties)

we were, regardless of our ethnic origins, still Orientals or Levantines, a people

who were just waking from centuries of slumber and ignorance, a people who

had been mistreated by foreigners, be they Turks, French or English, for their

own selfish interests.

In our new environments, temporary for most, permanent for few, we tried hard

to emulate the past. Customs were kept, rudiments of our mother tongue were

inculcated into our minds and traditions punctiliously adhered to. Lent was

strictly kept and for forty days no meats, poultry or fish passed our lips—at least

at home. For us children school meals (however tasteless they were) were our

salvation. I remember how I relished the school pork chops and steak and kidney

pies—especially during Lent.

Over the years changes did take place not only in our domestic lives but up and

down the land. More immigrants arrived from India, Pakistan, South East Asia,

Cyprus and the West Indies. They too soon settled down, opened their ethnic

restaurants, shops and emporiums thus enriching the country with their diverse

cultures and adding spice to the eating habits of the natives—particularly

important for one such as I who likes his food!

My early childhood was spent in Aleppo, Syria. My father’s family originated

from Cilicia (Southern Turkey) and my mother’s from Armenia. The Aleppo of

my childhood was a medium-sized cosmopolitan city soaked in history, rich in

commerce and perhaps the most enlightened region of the Levant. In our street

lived Armenians, Assyrians, Greeks, Christian Arabs, a well off Turkish family

with vast cotton fields and indisputably ugly slanted eyes and not forgetting

Jacob the Jew, a carpet dealer and close friend of my father. We all spoke our

ethnic tongues, with a little spattering of Arabic. We ate, prayed and lived our

lives as had our ancestors for centuries.

This is how my preface should have started: ‘The search and collection of

authentic recipes from the Middle East by Your’s Truly, an exile approaching

middle age and in search of his roots.’ Well, my roots were my family to whom I

turned in earnest, but with some difficulty. For although my family originated in

Armenia and Turkey we had, over the years, like the ‘sands of desert’, scattered

all over the east and beyond. So I got in touch with my aunt in Baghdad, my

cousins in Kuwait, my sister in Tehran, with other cousins in Egypt, friends of

cousins in Cyprus and Ankara, material cousins in Yerevan and Tiblisi and

numerous other friends of friends ad infinitum. Finally all those kind people I

encountered who had inadvertently ‘dropped in’ to have a meal in one of our

restaurants and who, throughout their meal (and often well after), were subjected

to a culinary inquisition of the fiercest kind. My thanks to all those people, with

special thanks to the young Saudi Arabian doctor who literally fell into my

clutches and had to spend an extra day in a wet and windy Manchester one

December until I was satisfied that I had squeezed the last drop of ‘culinary

blood’ from him. But most of all thanks to my mother who was a source of

inspiration and infinite information.

The result then is this book, a collection of recipes from all over the Middle East

regardless of political and geographical boundaries. By which statement I mean

the food of the people of the Middle East:1 Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians,

Azerbaijanians, Copts, Georgians, Kurds, Jews, Lazes, Palestinians, Persians,

Turkomans, Turks and all the other minorities who, far too often, are forgotten or

ignored by the cataloguers and generalizers of human achievements. For it is my

opinion that the true sources of most cultures are best found amongst the

indigenous minorities; e.g. the true Egyptian is the Copt, he is not only directly

descended from the Ancient Egyptians, but also still retains much of his

forefather’s culture undiluted by later arrived, desert-oriented Muslim Arabs.

I have also included proverbs, anecdotes, songs and stories of the famous

Nasrudin Hodja and Boloz-Mugoush all of which, directly or indirectly, relate to

food and all emanating from the rich and varied cultures of the peoples of the

Middle East, to whose glorious past and brighter future this book is dedicated.

All the recipes give the right amount of ingredients to feed four people unless I

have stated otherwise.

Arto der Haroutunian