Table Of ContentARSKY

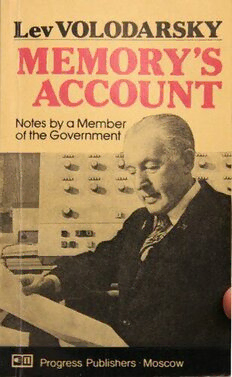

Lev VOLO

——

>

'

4

{

Notes by a Member

of the Government ’’ e{y f i vweis

= ee FY whe del

a

a

et

e

e

e

“ eoeee yee ~e%

(<]n} Progress Publ isners - Moscow

Translated from the Russian by Jane Sayer

Designed by Ivan Karpikov

Jles BononapcKkni

CYUET MAMSITH.

SANMHCKH YWIEHA TIPABHTEJIbCTBA

Ha aH2auuckom a3bike

© Us3ynatenpctso «IIporpecc», 1983

English translation © Progress Publishers 1983

Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

4702010200—454

B 014(01)—83 6e3 OObABA.

CONTENTS

A Note from the Author 9

Bread Comes Before Anything Else 9

“Whose Name Is Not a Word but a Banner” 25

The Hotel on Nevsky Prospekt 48

“YCL Squadron” 66

Code Number—‘‘OS 6” 74

A Feat of Labour and Spirit 91

At “Voznesensky’s School” 103

Fate’s Crossroads 118

The Reliable Figure 134

The Statistically Average Person? 145

My “Keys to Life” 171

We Need a Common Language 183

Our Point of View 202

Afterword 215

AT “VOZNESENSKY’S SCHOOL”

All my life I have been surrounded by good people,

people for whom a striving for knowledge, the

need to advance and improve themselves were the

rule. Among these people who exerted a major in-

fluence on me, and to a certain extent became exam-

ples for me, I would like to pick out, in particular,

Nikolai Voznesensky. I consider myself very lucky

that I encountered him several times in my life, both

directly and indirectly.

Infinitely devoted to his country, people and the

Communist Party, a man of tremendous knowledge

and fantastic ability to work, he was an _ excellent

leader and organiser, both demanding and attentive,

always ready to give assistance.

His direct influence on me began when I was

working as a Gosplan commissioner, and continued

when I was transferred from Leningrad to Moscow.

Counting the time when I read the first works by this

famous economist and considering that the skills I

acquired from working with him I find useful to this

day, the period of his influence covers virtually all

my working life.

At fifteen a YCL leader; at sixteen already a Com-

munist; at 32 a recognised research economist; at 34

the head of the country’s economic headquarters—

103

USSR Gosplan; at 37 First Deputy Chairman of the

Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR; at 39

a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences; at

43 a member of the Politbureau of the Party Central

Committee: such were the landmarks in Voznesens-

ky’s biography.

To me it seems worthwhile to judge a person from

the contribution he has made to the life of the coun-

try than to look at his personal characteristics. It 1s

my conviction many times proved in practice, that

the true role of a foresighted statesman may be as-

sessed according to qualities that go beyond the perso-

nal frame.

For me, the measure of a person has always been

the extent of his interest in his society, I am sure

that anyone who compares his everyday actions with

the interests of society and the people deserves deep

respect. Voznesensky was just such a person.

I recall that, right at the beginning of 1941, there

was a conference in Moscow. A group of comrades,

including myself, were given the task of preparing

its draft decision, precisely formulating in it the chief

guidelines for the future work of the USSR Gosplan

commissioners.

We drew up the draft carefully and considered the

final version to be complete. But a day later Vozne-

sensky proved to us all that the document was far

from perfect. Our definition of the commissioners’

functions and tasks did not include variants taking

into account the specifics of the various regions of the

country. Voznesensky was disappointed that we had

not considered the organisational aspects of transport

links between regions in sufficient detail. A few

months later we saw how right he had been: the war

104

p) raoskse eOvWa!c uawtiit:oh n naozf i ciGe teie zremnas nya nd ande quitphem e immedi at e,

|

iI |

uired. h

di

tur“WnHheoed wn to cwomeue l d waenyrdoe u , asCkeoddmi:sr causdsien g Votlheo dadrrsakfty,, Va oCzann deisednastkey

of Economics, have failed to take this into congiq.

eration?”

“Actually, ’m not a Candidate of Economics, but

that in no way excuses me,” I replied, since I had

not yet defended my thesis.

Voznesensky reacted instantly:

“Not a Candidate yet, but you will be. And a

D. Sc., too, if you understand correctly the extent of

your responsibility before the people. Examine your-

self in everything you do according to the highest

standards.”

I had known and heard a lot about Voznesensky in

Leningrad. In early 1935 Zhdanov asked for Voz-

nesensky to be sent to Leningrad to head the city

planning commission. His request was granted, and

among Leningrad economists the news was met with

approval.

Once Voznesensky arrived, the members of the

planning commission could hardly ever be found at

their desks—they were always in workshops, at public

amenities enterprises, on building sites, at tram ga-

rages, at factories, or in shops—each according to

his own field. Many of them really began to pene-

trate the economic life of the city for the first time,

feeling it not only through columns of figures, direc-

tives and documents, but in allits nuances and con-

tradictions. ‘This is what the new head wanted from

his subordinates,

105

As head of the USSR State Planning Committee.

Voznesensky began with the same delicate and com-

plicated matter—the selection and training of staff;

he sought experts with initiative, with a flexible and

efficient way of thinking. He made these demands on

any worker, whatever his post.

In order to turn the socialist planning bodies into

militant headquarters for checking on the fulfilment

of the national economic plans, Voznesensky put such

highly-qualified experts at the head of Gosplan that

they could converse a level with the heads of minis-

tries (people’s commissariats, as they were then

called). The Gosplan directives were distinguished

by a thrifty approach to the possibilities of both

each individual region and the state as a whole.

Economists began to talk about “Voznesensky’s

School’.

The “school” confirmed its vitality by rapidly trans-

ferring the economy of the huge country on to

military lines when nazi Germany attacked the

USSR.

In December 1942, it was suggested that I go to

Moscow. It did not take me long to get ready—my

possessions consisted of a small suitcase with essentials

and a couple of books. My departure was delayed by

the weather—for ten nights in a row I went to the

airport only to return in the morning.

Phone calls on behalf of Voznesensky came every

day, and sometimes he even rang personally to ask

why I had not yet left.

I explained.

On New Year’s Eve I left for Moscow. By mid-day

I was in Moscow and two hours later Voznesensky

received me. His first question was whether I had had

106

[ sa sat there until about 3 a.m., reading papers

plan. . aking of my family. At about four o’clock in

ing 1 went to my hotel then called “Asto-

at now “Berlin”, and spent the rest of the

ie Vveat’s night there. I ate a sandwhich and went

e

. ‘n April 1943 was I allowed to go to Sverd-

Ory the Urals, where my wife and family had

lovsk in th . ted. i d br; h

been since being evacuated, in order to bring them

back to Moscow.

When I arrived in Sverdlovsk I found out that,

the day before, they had already left for Moscow,

so we had passed each other on the way. The same

evening I had to take the train back. I could imagine

how my family would feel when nobody met them

at the station. But, as it turned out, I need not have

worried. Colleagues from Gosplan received the tele-

gram giving my family’s arrival time and met them,

helping them to get to Third Meshchanskaya Street,

where we had been given a flat. They had brought

in some food and a few essentials, and made some-

thing to eat.

When I arrived in the capital a couple of days

later, I came back to a virtually “lived-in” home.

There was a lot of work to do and I saw little of

on cmilly, Now, almost forty years since that spring

mena a lot has, of course, been erased from my

with "Ys a lot has been forgotten. But my meeting

My dear ones after the long, difficult period

of “€Paration

¢| b h

One of my m len brought me new strength h and and 11 S

Ost treasured memories.

107

Working in direct contact with Voznesensky, we

all passed through his same strict “‘school’’, where

the main subject was exactingness. From his subordi-

nates he demanded thoroughness and everything they

could give. He had a perfect knowledge of economic

proportions, the correlations between industries and

types of output, and believed that we should look

at all things broadly and, when solving partial prob-

lems, should always co-ordinate them with the gen-

eral tasks involved in developing the country’s econ-

omy, taking both inter-regional and_inter-industry

interests into account.

He would not accept a project unless the author

could prove convincingly, with specific calculations

and computations, not only the partial, but also the

overall benefit to be derived from it. Initially I was

concerned with fuel-supply problems. Whenever I

reported to Voznesensky on a possible Gosplan deci-

sion, I always took with me a sheet of calculations

going beyond the particular issue.

Voznesensky never brought pressure to bear with

his authority, never imposed his own view. He set

tasks in the form of the conditions of a precise prob-

lem; the solution and choice of methods he left to

his subordinates. He gave calm but not indifferent

approval of successful work, making it clear that

a good piece of work carried out by subordinates is

an honour for their head.

Once asked whether figures did not tire him, he

replied that, while words make it possible to com-

municate with one another, figures allow one to

communicate with time. To foresee and embody an

108

idea in calculations, and then make it reality: this

was the attraction of figures for Voznesensky.

In 1943, still long before the victorious end of

the war, Gosplan elaborated a plan for restoring the

national economy in regions liberated from nazi

occupation.

Some of our comrades thought that efforts and

means should be concentrated on restoring industry,

while housing could wait till the end of the war.

When Voznesensky heard such views, he would make

a dry and firm objection: “The war has caused the

Soviet people inexpressible difficulties. Yes, they could

survive even worse. But what they have survived is

enough. We must think about the peaceful future.

And tomorrow the Soviet man must both work and

live under normal conditions.”

He insisted that the maximum possible funds be

allocated for restoring housing and that a special day-

to-day accountability be instituted—the Gosplan com-

missioners had to report every five days on how

many people had been moved to new or repaired

houses.

During the restoration of the national economies

of the liberated regions, the Government set the task

of not simply recreating what had existed before, but

also of considering this as a reconstruction process

making it possible, in addition to attaining the prewar

level of production, to iron out the defects that had

existed before the war in the location of productive

forces. We were to locate large enterprises close to

raw material sources and, where possible, duplicate

these sources. When restoring towns and _ villages,

their old lay-out was to be reviewed, taking into

account the prospects for development, and the geo-

109