Table Of ContentMEAN … MOODY … MAGNIFICENT!

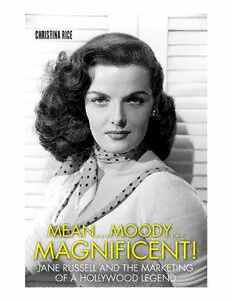

MEAN … MOODY … MAGNIFICENT!

Jane Russell and the Marketing of a Hollywood Legend

Christina Rice

Copyright © 2021 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky,

Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky

State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Spalding University,

Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights

reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are from the author’s collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rice, Christina, 1974– author.

Title: Mean … moody … magnificent! : Jane Russell and the marketing of a Hollywood legend / Christina Rice.

Description: Lexington, Kentucky : University Press of Kentucky, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references, filmography,

and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021006503 | ISBN 9780813181080 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780813181103 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813181097

(epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Russell, Jane, 1921–2011. | Actors—United States—Biography.

Classification: LCC PN2287.R82 .R53 2021 | DDC 791.43/028092 [B]—dc23

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in

Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of University Presses

For my daughter Gable,

who is neither mean nor moody,

but always magnificent.

Contents

Preface

Introduction

1. From Bemidji to Burbank

2. Valley Girl

3. Daughter Grows Up

4. Accidental Aspiring Actress

5. The Howards

6. Shooting an Outlaw

7. Motionless Picture Actress

8. Mean … Moody … Magnificent

9. Mrs. Robert Waterfield

10. Kick-starting a Career

11. House in the Clouds

12. Mitch

13. Wing-Ding Tonight

14. International Uproar

15. What Happened in Vegas

16. Blondes

17. A Woman of Faith

18. J. R. in 3D

19. WAIF

20. Russ-Field

21. Do Lord

22. On the Stage and Small Screen

23. Endings, Beginnings, and Endings

24. A Life Off-screen

25. Path and Detours

26. Living Legend

Acknowledgments

Filmography

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Preface

When my book on Ann Dvorak was published in 2013 after fifteen years of tears and toil, I

was determined to be done with writing movie star biographies. The commitment was too

great and the uphill battle too brutal. To ensure I wouldn’t subject myself to another Dvorak-

like odyssey, my husband even introduced me to the editor of the My Little Pony comic book

series, and I ended up writing more than twenty-five issues, much to the delight of my young

daughter. While I was able to pay homage to my love of classic film in the pony world of

Equestria (King Vorak, a character I created, was even mentioned in the finale of the My

Little Pony television series), I should have known the urge to write about the women of

Hollywood’s golden age would overcome common sense.

Only a few months after Ann Dvorak: Hollywood’s Forgotten Rebel was published, I

reached out to Patrick McGilligan with the University Press of Kentucky for thoughts on who

would be a good subject for a second book. I was leaning toward Aline MacMahon, whom I

had been introduced to while researching Ann Dvorak, but Patrick was in favor of someone

with more name recognition than Ann, not less! Had I ever considered Jane Russell? I had to

admit I hadn’t. Sure, I adored her opposite Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and

had managed to suffer through The Outlaw once, but did I really want to spend a few years

immersed in the world of Jane Russell? There was no denying she still had a lot of name

recognition. After all, in addition to her film star status, a generation had grown up watching

Jane advocate for the comfort of “full-figured gals” in Playtex bra commercials. I was

surprised to discover that other than her 1985 autobiography, no books had been written

about Jane. I was vaguely aware of Jane’s conservative Christian beliefs, which generally did

not line up with my own worldviews, and which I suspected had turned off other writers.

This aspect of her life did give me pause, but after mulling over the project for almost a year,

I finally decided this exceedingly complex woman was a challenge I wanted to take on.

The journey with Jane was a very different one than with Ann Dvorak. Whereas Ann was

a bit of an enigma, and primary source documents related to her proved difficult to track

down, Jane was a hyper-documented open book. She was the product of endless controversy

due to Howard Hughes’s marketing of her and her films, so interest has been high for

decades, and she received a lot of press coverage. Jane lived to be almost ninety and always

made herself available for interviews, so letting her speak for herself in these pages was easy.

I found Jane to be so no-nonsense and unconcerned with keeping up appearances that she

turned out to be a consistently reliable narrator, which is a gift for a biographer. However,

writing about Jane Russell also proved to have its own unique challenges. She was

exceedingly outspoken, particularly as she got older, and sometimes spouted off right-leaning

political views that didn’t always paint her in a positive light. Still, they are part of her story

and could not be ignored.

Jane’s stated beliefs were frequently out of alignment with her actions, which I found

extremely maddening. Here was a proud, lifelong Republican who was also a staunch

supporter of government child welfare programs; she once had to aggressively lobby

Congress to save a bill funding foster care that had been passed by the Carter administration

but nearly killed under Reagan. Jane actively favored a career over a life of domesticity and

agreed that women should be compensated equally to men, but often derided feminism as a

lot of nonsense. She told at least one journalist that homosexuality was unnatural, but she

eagerly accepted an invitation to a screening of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes preceded by a

Marilyn and Jane drag performance. She once described herself as a “mean-spirited, right-

wing, narrow-minded, conservative Christian bigot,” but close friends dismissed these

comments as Jane just being her outspoken self and not expecting to be taken seriously. Jane

understood the power of her celebrity to help accomplish the goals of her WAIF foundation,

formed in aid of adopted children, but never seemed to grasp how her comments could affect

the many nameless individuals who admired her.

Recently I was having dinner with a group of friends who were all gay men. The subject

turned to Jane and one of them mentioned how he had idolized her as a youth. She had

become a gay icon, largely due to the “Ain’t There Anyone Here for Love?” number from

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and he had gravitated to Jane, picturing her as someone fierce and

fabulous who would accept him for who he was. When he later learned of her views of the

LGBTQ community, he was devastated. The conversation about Jane continued, but I noticed

he became silent, his expression solemn. Had Jane been there, I have no doubt she would

gladly have pulled up a chair and thrown back a few drinks with us. I also think she would

have been genuinely perplexed as to why my friend could have been so affected by anything

she had to say. She never seemed to understand how contradictory she could be, and that her

words really did resonate with others.

Ultimately, my feelings for Jane are conflicted. I love watching her onscreen. There, she

is a larger-than-life personality, a true product of the golden age who is often a complete joy

to behold. Off-screen she is equally fascinating, often admirable and sympathetic, while at

the same time perplexing and disappointing. In other words, the movie star turned out to be

devastatingly human. Still, writing this book is a journey I am glad I took, and the life and

career of Jane Russell are interesting and worth exploring.

While the Ann Dvorak odyssey left me emotionally drained, I felt the opposite with Jane.

One of the things I found most admirable about Jane was her self-confidence. That aspect of

Jane seems to have rubbed off on me, and I look forward to discovering my next book

project, whatever or whoever it may be.

Introduction

Another long day in Arizona was wrapping up and Jane just wanted to go to sleep. After all,

if she didn’t get her nine hours in she could be a bear. However, she was well aware that here

in the small Hopi village of Moenkopi, she needed to be on her best behavior, both charming

and accommodating. Only nineteen, she had been given a huge break in the fall of 1940,

handpicked by eccentric multimillionaire Howard Hughes to co-star in his latest big-screen

production, The Outlaw, a retelling of the legend of outlaw Billy the Kid. With Howard

Hawks, one of Hollywood’s most capable and versatile directors, at the helm, Jane knew this

was the opportunity of a lifetime. Normally a no-nonsense type of gal, she was starting to

understand that being Howard Hughes’s latest discovery was going to require tolerating a

certain amount of, well, nonsense.

A group of photographers had been invited to join the cast and crew on location and it

soon became apparent to most what they were there to photograph. “Pick up those buckets,

Jane!” “Bend over and pretend you’re using the axe, Jane!” Over and over, the photographers

found creative and not so subtle ways to shoot down the front of Jane’s peasant blouse,

presumably at the request of Russell Birdwell, the PR guru who had been hired by Hughes to

promote the film. Some of the photogs even climbed up on rocks in order to angle their

cameras downward to get the perfect shot of her cleavage. Jane, young and naive, was

clueless about what was taking place. “I had no idea what they were seeing,” she would later

say of where the photographers’ cameras were pointing.1 However, she soon got wise to what

was happening.

The breaking point came when one of the photographers came to her room on location

one evening. It wasn’t even a room, really, just a large tent. The cameraman would later

recall that when he asked Jane to put on a low-cut satin nightgown, she seemed “unfazed.”2

She obligingly struck several suggestive poses—leaning over the sink to brush her teeth,

leaning forward while reading a magazine, throwing her chest out while stretching in the

entryway. The shoot culminated with Jane, at the photographer’s request, jumping up and

down on the bed. But she was far from unfazed—after the photographer left, she finally

broke. Jane knew she had been hired because of her looks, and more specifically her body,

but bouncing on a bed in a dirty Arizona tent in her nightgown was too much. As panic set in

and the tears came, she got dressed and went to see the one person on set she knew she could

trust.

Photographer Gene Lester later said Jane was unfazed by his request that she jump on the bed for a photo. This was far from

the truth. (Gene Lester via Getty Images)

Jane had unexpectedly lost her father three and a half years earlier, and in her eyes

Howard Hawks had quickly filled that role, at least for the brief time they would be working

together on this film. Yes, “Father Hawks” would provide a shoulder to cry on and put a stop

to this. However, when she went to her director, she was not consoled as she had hoped.

Instead, Hawks looked impassively at Jane’s tear-stained face and responded with zero

emotion. “Look, you’re a big girl, and you’ve got to protect yourself. If someone asks you to

do anything that’s against your better judgment, say NO! Loud and clear…. You’re in charge

of you. No one else.”3

With those few words, Howard Hawks freed Jane Russell. She was smart enough to know

that her physical attributes would be her bread and butter if she continued a career in films,

but she was now empowered. She was the one who could—and would—draw the line, the