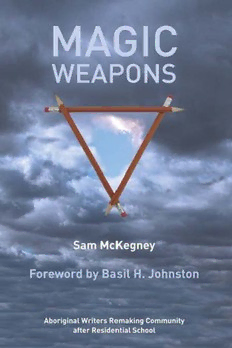

Table Of ContentMAGIC

WEAPONS

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in1 1 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in2 2 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

MAGIC

WEAPONS

Aboriginal Writers

Remaking Community

after Residential School

Sam McKegney

Foreword by

Basil H. Johnston

University of Manitoba Press

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in3 3 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

© Sam McKegney, 2007

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N2

www.umanitoba.ca/uofmpress

Printed in Canada by Friesens.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or

by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of

University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence

from ACCESS COPYRIGHT (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), 6 Adelaide Street East, Suite

900, Toronto ON M5C IH6, www.accesscopyright.ca.

Cover and text design: Grandesign Ltd.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McKegney, Sam, 1976-

Magic weapons : Aboriginal writers remaking community after

residential school / Sam McKegney.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-88755-702-6

1. Canadian literature (English)—Indian authors—History and criticism. 2. Canadian literature

(English)—Inuit authors—History and criticism. 3. Indians of North America—Canada—

Residential schools. 4. Inuit—Canada—Residential schools. 5. Indians of North America—

Canada—Ethnic identity. 6. Inuit—Canada—Ethnic identity. I. Title.

E96.2.M325 2007 C810.9’897 C2007-904064-0

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication

program provided by the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry

Development Program (BPIDP), the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Arts Council, and

the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Tourism.

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in4 4 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

CONTENTS

Foreword by Basil H. Johnston vii

Acknowledgements and Permissions xvii

INTRODUCTION 3

1. ACCULTURATION THROUGH EDUCATION 11

The Inherent Limits of ‘Assimilationist’ Policy

2. READING RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 31

Native Literary Theory and the Survival Narrative

3. “ WE HAvE BEEN SILENT TOO LONG” 59

Linguistic Play in Anthony Apakark Thrasher’s Prison Writings

4. “ ANALYzE, IF YOU WISH, BUT LISTEN” 101

The Affirmatist Literary Methodology of Rita Joe

5. FROM TRICKSTER POETICS TO TRANSGRESSIvE POLITICS 137

Substantiating Survivanace in Tomson Highway’s Kiss of the Fur Queen

CONCLUSION 175

Creative Interventions in the Residential School Legacy

Endnotes 183

Bibliography 221

Index 235

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in5 5 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in6 6 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

FOREWORD

U

ntil I read Magic Weapons I didn’t realize that those of us who had at-

tended residential school and then written about some of our experi-

ences could cause such an uproar in the academic world so as to open

the floodgates of the sea of deep thoughts and let loose a torrent of words.

Reminded me of my father, Rufus’s, astonishment when I told him of my new-

found knowledge that I had gained upon joining the ranks of scholars at the Royal

Ontario Museum in Toronto in 1970. I told him that I had learned that our An-

ishinaubae words fell into two categories, animate and inanimate; and that our

verbs had a tense called “dubitative” that English didn’t have. Dad stood, as if

dazed, for some moments before remarking, “Gee Whitakers! I didn’t know that

we were that smart!”

Like my father, I’m taken aback to learn that our words had such impact as to in-

cite debates in the academic world. I didn’t know that we, myself included, meant

to heal, empower, and help people find their identities. If the works of Highway,

Thrasher, Joe, and myself bring about these results, well and good.

But I didn’t have such lofty aims when I wrote Indian School Days. Mine were

much more modest. It was simply to amuse the readers of The Ontario Indian,

a magazine of the Union of Ontario Indians that ceased publication in the

mid-1980s.

After graduation from residential school in 1950, I and ten other former inmates

of the school went to Wawa to work in the mines. There we formed a sort of com-

munity, often reliving some of our experiences while we were locked up in the

Spanish school. For five summers I worked in Helen Mine, consorting with my old

schoolmates; as always, we rehashed old memories.

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in7 7 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

MMAAGGIICC WWEEAAPPOONNSS

Upon my graduation from Loyola College, Montreal, Quebec, I went to Toronto.

In the late 1950s there may have been fifteen former Spanish residential school stu-

dents working in Toronto. We found each other and kept in touch, drawn together

by our common background and heritage and training in residential school.

At home in Cape Croker, there were more than thirty people who had gone to

residential school: my father, mother, uncles, and many others, who said not a

word about their years at Spanish to us, their children. Eugene (Keeshig), Hector

(Lavalley), Charlie (Akiwenzie), and I talked about residential school, but not to

our children.

When I started writing some of the stories that originated in Spanish and its

residential school, former students came to me or called me to tell me more sto-

ries. “Write a book! Why don’t you write a book?” they said.

And that is how Indian School Days came into being. First, it was intended to

amuse readers, to recount and to relive some of the few cheerful moments in an

otherwise dismal existence, a memorial to the disposition of my people, the An-

ishinaubaek, to find or to create levity even in the darkest moments. And this is

how I would like my book to be seen.

Had I known what I now know, perhaps I might have written an entirely dif-

ferent text. But I didn’t know what I know now, and not knowing would have

trivialized the residential school experience. But it’s not likely that I would have

changed the purpose I had in mind in setting pen on paper to write about my

schoolmates and friends.

When word got out that I was writing about Garnier Residential School, I’ve

reason to believe that there were a few uneasy Jesuits. One day Father Felix, then

pastor of St. Mary’s Catholic Church on the reserve, remarked with a smirk,

“Heard you’re writing about Spanish. Please don’t exaggerate as writers are in the

habit of doing!”

“You needn’t worry, Father!” I replied. “My account is a model of restraint!”

Even afterwards, I heard from Father Wm. Maurice that none of the stories were

documented or dated, and from Miss Alice Strain that they were all lies.

In 1959 the former students of the Spanish Residential School held a reunion.

Many did not come, too bitter to come to the scene of their degradation and hu-

miliation. After two days of speeches, religious exercises, eating, and reliving hor-

rors and capers, we went home. That so many came may be seen as customary

among Indians; they like to visit and to revisit old times.

viii

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in8 8 17/10/07 10:00:37 am

FFOORREEWWOORRDD

I think it was around 1995 that I heard rumours of a lawsuit being launched

against the Jesuits and the federal government by former students of the Spanish

Residential School. I heard that a lawyer from Meaford, Ontario, had been retained

to represent the plaintiffs.

I wasn’t interested. I wanted to get on with life. Besides, I didn’t want my wife,

Lucie, to know that she had married damaged goods and that I had not trusted

enough in her love to confide in her what had been done to me at school.

One Saturday afternoon I left the house to drive around the community and take

in the sights of home, my roots. Around the band administration building were cars.

Must be important, I thought, for so many people to give up going to town on a

glorious Saturday afternoon; there must be something special going on.

As a rule I avoid public meetings. But something drew me to stop and drew me

to the building.

Inside was a large crowd. As I stepped into the dim interior, the gentleman

standing at the head of the table asked what I was doing at the meeting meant only

for residential school survivors.

“He’s one of them, one of us,” the people sitting around the table spoke before

I could explain.

I gave my name, then sat down as invited.

The gentleman conducting the meeting, which was primarily an information

session, was John Tamming, a lawyer from Meaford, Ontario, who had been re-

tained first by Renee Buswa and his wife of Whitefish Falls, Ontario, back in 1996.

When the lawsuit was converted into a class action lawsuit, Mr. Tamming was

retained to represent hundreds of complainants from the Spanish Residential

School.

I was, as it were, roped into the class action lawsuit.

As one of the parties in the action against the Jesuits and the federal govern-

ment, I had to make an affidavit declaring that the violations inflicted upon me

during my incarceration in residential school actually occurred.

In preparation for the interview with Mr. Tamming, I girded myself to tell the

story that I’d never told anyone before, without breaking down. But I broke down.

I wept.

Why did I weep? Shame! Guilt! I don’t know. Did I feel relief? I don’t know. Did

I feel better? I don’t know.

For years I had laboured under the conviction that I was the only one to be

debauched in Spanish Residential School. But during the course of the meetings

ix

MgkWpns-textpgs-proof 6 FINAL.in9 9 17/10/07 10:00:38 am