Table Of ContentCONTENTS

Foreword by Carl Levy

Editor’s Introduction to the First Edition

Editor’s Introduction to the Third Edition (1984)

PART ONE

Introduction: Anarchy and Anarchism

I

1. Anarchist Schools of Thought

2. Anarchist—Communism

3. Anarchism and Science

4. Anarchism and Freedom

5. Anarchism and Violence

6. Attentats

II

7. Ends and Means

8. Majorities and Minorities

9. Mutual Aid

10. Reformism

11. Organisation

III

12. Production and Distribution

13. The Land

14. Money and Banks

15. Property

16. Crime and Punishment

IV

17. Anarchists and the Working Class Movements

18. The Occupation of the Factories

19. Workers and Intellectuals

20. Anarchism, Socialism, and Communism

21. Anarchists and the Limits of Political Co-Existence

V

22. The Anarchist Revolution

23. The Insurrection

24. Expropriation

25. Defence of the Revolution

VI

26. Anarchist Propaganda

27. An Anarchist Programme

PART TWO

Notes for a Biography

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Appendix IV

PART THREE

Malatesta’s Relevance for Anarchists Today

Notes

Index

F

OREWORD

by C L

ARL EVY

E

RRICO MALATESTA (1853–1932) WAS BORN IN SANTA MARIA CAPUA Vetere near

to Naples. His family were middle-class tannery owners, and he was not,

as the press would have it, a count who conspired with other aristocrats

such as Peter Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin. Malatesta lived between the era of

the Paris Commune and Russian Revolution and the establishment of the Fascist

dictatorship of Benito Mussolini. He knew Bakunin and Mussolini and was

known and appreciated as a revolutionary (at least initially) by Vladimir Lenin.

Although the young Malatesta was a key figure in the First International in Italy

and elsewhere, his presence in Italy was mainly between 1885 and 1919, when his

reappearances occurred during periods of popular unrest: the 1893–94 Fasci

Siciliani, the risings of 1897–98, La Settimana Rossa (The Red Week) of 1914,

and finally the Biennio Rosso (Red Biennium) of 1919–20.1

For a large part of his adult life, Malatesta was an exile and spent nearly thirty

years in London, then the “capital” of the capitalist world.2 He is an exemplar of

the cosmopolitan nomadic radical who circulated through the circuits of world

imperialism, transporting an alternative modernity to that of the Gatling gun, the

Holy Bible, and the imperialist iron regime of the mine, the plantation and the

factory. Malatesta lived, organized, and fought in Egypt, the Levant, the Balkans,

Spain, Argentina, the United States, Cuba, Switzerland, and France. The most

exciting recent work on anarchism and syndicalism before 1914 is now focused

on the dissemination and reception of anarchist and syndicalist repertoires of

action, thought, and culture in the Global South as well as the tracing of

transnational networks of libertarian diasporas in port cities and elsewhere.3

Malatesta’s life is emblematic of this process that allowed anarchists and

syndicalist currents to have far greater influence on the global Left than mere

numbers would suggest. A sociology of these networks reveals several

generations of intellectuals like Carlo Cafiero,4 Francesco Saverio Merlino,5 and

Luigi Fabbri,6 who were ideological comrades and sounding boards for his ideas,

and several generations of self-taught workers and artisans from the anarchist

seedbeds of Liguria, Tuscany, Umbria, the Marches, and Rome who kept his

presence alive in Italy even if he rarely set foot in his native land.7 And one of

these self-taught anarchists was Emidio Recchioni, the father of Vernon

Richards, the author and editor of this very book.8 Malatesta never finished his

medical degree at the University of Naples and became an artisan: he trained as a

gas-fitter and electrician, and between his stints as an organizer and radical

newspaper editor he always returned to his trades, even in old age in Rome

during the 1920s. Like the Russian populists he sought to declass himself and go

to the people, and he feared and detested the development of a class of left-wing

professional journalists, orators, and politicians who fed off the social

movements and betrayed their principles.

Malatesta lived in a modern, globalized world of the steamship, the railroad,

the telegraph, and dynamite.9 And although he fought a brave battle against the

anarchist terrorism and expropriation inspired by Ravachol and Henry in the

1890s or in the new century of Parisian tragic bandits and Latvian

revolutionaries turned robbers consumed in the fires of the Siege of Sidney

Street, he never endorsed pacifism, wrote long articles against the followers of

Tolstoy, and remained a revolutionary inspired by, though critical of, the

followers of Mazzini during the Risorgimento. Like many Italian anarchists of his

generation, his political apprenticeship was forged in the disappointing

aftermath of the Italian struggle for unification and independence.10 Although he

renounced Mazzini and the Republicans when the old nationalist revolutionary

disavowed the Paris Commune for its atheism and promotion of class war,

Malatesta always retained deep ethical and voluntarist strains in his thought and

political action, maintained a fruitful dialogue with the Italian Republicans, and

indeed formed an alliance through a mutual struggle against the Savoy dynasty.

Thus in 1914 this alliance of anarchists, anti-militarists, syndicalists, republicans,

and maverick socialists nearly brought the regime to a crisis before the First

World War rearranged the political field. But even after the war, during the

Biennio Rosso and the years leading to the creation of Mussolini’s dictatorship

(1922–26), Malatesta sought alliances with the maverick left and the republicans

to prevent or overthrow the growing power of the new Fascist movement and its

installation in power with the support of the Savoyard king in Rome.11

Malatesta advocated the establishment of a national federation of anarchist

groupings—internationalists, anarchist socialists, and then plain anarchists—in

Italy from the 1870s to the 1920s, and for this he received strong criticism and

indeed abuse from the individualists, Stirnerites, and the affinity group anarcho-

communist anarchists associated with his old comrade Luigi Galleani.12 But he

was not an advocate of an anarchist revolution as such. The social revolution

would be guided by small-‘a’ anarchist methods but an anarchist party would not

be the invisible pilot behind its success. That is why he later looked back on the

quarrels between Marxists and Bakuninists in the First International and felt

them both to be in the wrong. He argued with Mahkno and the Platformists in

the 1920s because they seemed to be advocating an anarchist form of Leninism.

The denouement of the Bolshevik Revolution did not surprise him. Like

Bakunin, he predicted that a Marxist revolution would result in a dictatorship of

a New Class of ex-workers, intellectuals, and politicos. All social organisations

might be prey to an “iron law of oligarchy,” as German sociologist Robert

Michels termed it. Albeit, Malatesta took exception to the concept of “iron laws”

in political and social life; thus he objected to his fellow London exile

Kropotkin’s marriage of biological concepts of mutual aid with the open-ended

business of human politics. He fought all determinisms and indeed

foreshadowed the critique of many recent post-anarchists who have lambasted

“classical anarchism” for its determinism, essentialism, and Whiggish teleology.

Nevertheless, Malatesta argued that anarchist or syndicalist trade unions would

be prey to the same maladies as the moderate, socialist, or communist ones. The

only remedy was for anarchists to work in “ginger groups” in all trade unions

and promote libertarian methods: rank and file control, circulation of leadership,

and low salaries for these temporary leaders.13

Trade unions were important for Malatesta. Although he never renounced

the role of insurrection in making the revolution, by the 1880s and 1890s, with

the massive London Dock Strike of 1889 in mind, he advocated a syndicalist

strategy to the first generation syndicalist French anarchist exiles in London

during the 1890s. When syndicalism grew worldwide in the early twentieth

century he pointed out the theoretical and practical weaknesses of its workerism

(the revolution was broader than that) and the fact that a peaceful general strike

would merely result in the starvation of the urban working classes and the

collapse of the strike if it wasn’t brought to a quicker termination by the State’s

armed forces and vigilante groups. When the factories of northern Italy were

occupied in September 1920, Malatesta suggested that the workers recommence

production and distribution links and not await events or negotiations. The

modern city had to be restarted by the revolutionaries on their own initiative if

the occupation was not to falter and lead to an inconsequential negotiated

settlement.14

But Malatesta did not ignore the countryside and, like Bakunin, saw the

tremendous revolutionary potential in the peasantry, and some of his most

widely read pamphlets were aimed at landless laborers and smallholders. Unlike

the Italian Socialists in 1919–20, he warned against the promotion of the rapid

socialisation of the land which drove the smallholders into the hands of the

Fascists. A class war between the landless laborers and the smallholders was a

war between the poor and the poorest and allowed Fascism to sweep away the

Red Zones around Bologna and Ferrara in the spring of 1921; starting a rapid

process to allow the former and largely discredited radical socialist Benito

Mussolini in 1919, ascend to prime minister by the autumn of 1922.15

Malatesta also argued that small-‘a’ anarchism was the only method by which

the reformists had won their dubious victories: the expansion of the suffrage to

the male British working class or the struggle for female suffrage in early

twentieth century Britain, which Malatesta witnessed and had known many of

the key personalities in the fight, had been won from the ruling classes through

direct action not peaceful petition and rallies, he argued, over and over again. But

he was not averse on occasion to forming alliances with moderate socialists, anti-

clericals, and even liberals if the State threatened the space of civil society in

which the anarchists could organize and make their case. Thus he endorsed such

broad alliances in Italy when civil liberties were threatened during the 1890s,16

during the road to Fascism in the early 1920s, and under the Fascist regime from

his condition of near-house arrest in Rome from 1926 to his death in 1932. But

Malatesta would under no conditions stand as a protest electoral candidate as

suggested by the former anarchist intellectual and activist Saverio Merlino, who

by the turn of the century endorsed a maverick form of libertarian social

democracy. Of course Malatesta was not naive: he was no admirer of liberal

politicians, such as Lloyd George, whom he termed a hypocrite. He understood

the realities of the republican United States in the Gilded Age: industrial welfare,

lynch law, nativism, and the unbridled racist jingoism of the Spanish-American

war were commented on by Malatesta, who had spent 1900–1901 in the Italian

anarchist colony of Paterson, New Jersey, and in U.S. occupied Havana. He knew

full well that his near-deportation from London in 1912 was prevented by a

united front stretching from MPs such as Ramsay MacDonald and Keir Hardie

in the British Labour Party, trade unionists both moderate and syndicalist,

Radical Liberals and less radical liberals of the broadsheet press, and even his

neighbourhood Islington’s “free-born Englishman” (sic) Fair-Trade Unionist

(Tory) newspaper. But a united front which involved a careful calibration of

direct action when the British government was threatened by industrial unrest,

the troubles in Ireland and the suffragettes as well as the pressure of radical and

liberal elite networks (indeed one might add “old boy’s networks”), which

worked to Malatesta’s advantage.17

The First World War brought a major split among the most famous

personages of international anarchism, especially a fierce debate against

Kropotkin, who not only endorsed the Entente and Allies but became a bitter-

ender and demanded a continuation of the war in 1916, even when some senior

British Tories were demanding a truce and a negotiated settlement. Malatesta

remained opposed to the war and witnessed how the war reactivated the

industrial radicalism of pre-war syndicalism in the factory council movements

and free soviets of Italy and the wider world.18 He felt in 1917 that the expelled

anti-parliamentary socialists and anarchists of the London congress of the

Second International in 1896,19 in which he fought on the anarchist side, had

been vindicated as wartime and (later) post-war socialist and industrial

radicalism seemed to be adopting or perhaps adapting pre-war anarchist and

syndicalist positions. But by the 1920s and the triumph of Fascism and

Bolshevism and the decline of anarchism in many of its former strongholds,

Malatesta returned to the basics and engaged in some of his most penetrating

journalism on themes of the essence of anarchism, anarchism and violence, and

the role of liberalism and spaces for anarchism in civil society. When classical

insurrectional anarchism faded after 1945, Malatesta’s legacy of an open-ended

and non-scientistic anarchism was adapted by “reformist” anarchists such as

Colin Ward.20 One of Ward’s closest comrades in the post-1945 British anarchist

movement was Vernon Richards.

Vero Benevento Constantino Recchioni was born in London in 1915 and

later anglicized his name to Vernon Richards.21 As previously mentioned,

Emidio Recchioni had been an active anarchist mainly in Ancona before his

arrival in London in 1899, which had been preceded by his imprisonment on the

penal island of Pantelleria where he made the acquaintance of Luigi Galleani, a

fellow prisoner. During the 1890s Emidio had been employed with the Italian

railroads, and this facilitated easy access to other comrades throughout the

anarchist seedbeds of central Italy. During the 1890s he may have been involved

in an attempt on the life of the authoritarian prime minister Francesco Crispi. In

London he quickly opened a noted Italian delicatessen, King Bomba, which

became a meeting place for two generations of anarchists and radicals, including

Malatesta’s inner circle when they visited London and the local Malatestan

anarchists, and later in the 1920s and 1930s Sylvia Pankhurst, whose partner,

Silvio Corio, was another Italian anarchist exile in London, and Emma Goldman

and George Orwell. The financial success of the shop allowed Recchioni to help

finance Malatesta’s major newspapers in Italy in 1913–15 (Volontà), 1919–22

(Umanità nova), 1924–26 (Pensiero e Volontà), and later funded several attempts

on Mussolini’s life.22 Under the pen-name “Nemo,” Recchioni was an avid

contributor to the Italian anarchist press and to Freedom, the newspaper founded

by Kropotkin in London in 1886. His contributions to the newspaper are still of

great interest, especially an article in 1915 in which he predicted a new form of

radicalism in a post-war Europe, rather close to the council communism and

militant factory shop stewards movements of the period 1917–20 before they

were undermined by the rise of Leninist communism and suppressed by the

restoration of the bourgeois order.23 He died in 1934, but his son Vero carried on

the family politics.

Vernon Richards received his education at Emmanuel school in Wandsworth

and then graduated in civil engineering from King’s College London in 1939. In

his youth he was an accomplished violinist but later let this lapse. In 1934 he

became active in the struggle against the Fascist regime of Mussolini and was

deported from France where he fell in love with the daughter of the anarchist

Camillo Berneri, Marie-Louise. Camillo Berneri was from the next generation of

Italian anarchists after Luigi Fabbri and helped modernize its scope with

important works on inter-war anti-Semitism, a critique of “worker-worship” and

the adaption of the concepts of mass society, psychoanalysis, and totalitarianism

for understanding the rise and strength of Fascism and Stalinism in the 1930s.

He was murdered in Spain during the May Days of 1937 in Barcelona, most

probably by Stalinist agents disguised as Spanish Republican Guards. Berneri had

criticised the policies of the CNT-FAI: the joining of the Popular Front

government, the lack of a guerrilla war, the sacrifice of the social revolution for a

militarised war effort and the lack of a campaign to undermine Morocco, the

original base of the Nationalists and the Army of Africa, by engaging in anti-

imperialist agitation in the Spanish-controlled portion of that country.24 These

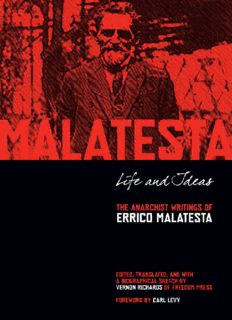

critiques would reappear in one of Vernon Richards’s most cited works, The

Description:Life and Ideas gathers excerpts from Malatesta’s writings over a lifetime of revolutionary activity. The editor, Vernon Richards, has translated hundreds of articles by Malatesta, taken from the journals Malatesta either edited himself or contributed to, from the earliest, L’En Dehors of 1892, t