Table Of Contentois i

|

\

q

SDT

)

SE

PN i, ee

;

CL

f \

B LUCE

om |

1

s SS af

IAD

\ ® ~~ ao |

beginners

S

: > ae “

i d

| ng me =

=a:= ae =} > | } i

5

"3

SOOLy a tf >. U[4 pS sf Rees — eiet i ae- BS: ye =

x% PV :

Sa 9

ese

re ah

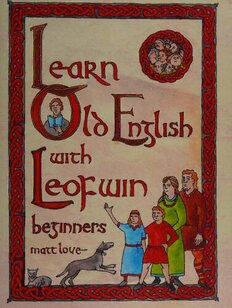

Learn Old English with Leofwin

Matt Love

First Published 2013 by

Anglo-Saxon Books

Hereward, Black Bank Business Centre

Little Downham, Ely, Cambridgeshire CB6 2UA England

Printed and bound by

Lightning Source

Australia, England, USA

Revised March 2014

© Matt Love

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photo-copying, recording or any information storage or

retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the

publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in connection with

a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper.

This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed

of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that

in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

ISBN 9781898281672

To the memory of my Mum and Dad

Thanks for everything

Unregarded, unrenowned,

men from whom my ways begin.

Here I know you by your ground,

but I know you not within —

there is silence, there survives

not a moment of your lives.

Edward Blunden, Forefathers

Contents

Foreword

Going Back in Time — New English to Old English

A note on Old English Writing and Pronunciation

How to Use this Book

Meet Leofwin!

Leornungdeel 1 — min cynn / my family

Leofwin’s family

Family questions

More about Leofwin’s family

Leofwin’s neighbours

Wesan - ‘to be’

Hatan — ‘to be called’

Family phrases

Yes and no

Likes and dislikes

Numbers 1-30

More family vocabulary

Foxtail describes his family

Mini-essay: Anglo-Saxon Families

YA Leornungdeel 2 — min his / my house

Leofwin’s house

House vocabulary

Gender — some grammar!

Describing people

Golde describes her family

Describe your family

Spreculmuth’s family

Some more characters

Meet Aelfgifu

Béon — ‘to be’

Habban — ‘to have’

Colours

Translation!

Eth and thorn — two Old English letters

Mini-essay: Farmsteads, villages and towns

page 39 Leornungdeel 3 — iite / outside

39 1 Where Leofwin lives

40 2 ‘oneardian’ - to inhabit

40 3. Plurals - examples so far

42 4 Plurals — strong and weak nouns

43 5 Strong and weak nouns - test

44 6 Leofwin describes his village

46 7 Some verb patterns

47 8 Animals

48 9 Consolidating plurals - strong and weak nouns

48 10 Subjects and objects — more grammar!

49 11 Weak nouns

51 12. Word order

51 13 (aand b) Basic survival guide — some essential phrases

54 14. Mini-essay: Prittlewell in Anglo-Saxon times

55 Leornungdeel 4 — timan, weder / seasons, weather

55 1 The four seasons

56 2 Reading task (easy!), and discussion on verbs

oy| 3. Fairly easy translation task

58 4 Foxtail describes the seasons — and offers a feast of verbs

60 5 Grammar task on verbs

61 6 Months of the year (harder than you’d think)

63 7 Birthdays

64 8 Numbers 31 — 100

65 9 Weather

66 10 Clufweart talks about the weather

67 11 Writing about the weather yourself

67 12 Revision of greetings

68 13. Days of the week

69 14. (a) Times of the day

(b) Hours of the day

70 15 Mini-essay: dividing the year

7 Leomungdeel 5 - gesceaftlice woruld, gedaeghwamnlic lif / natural world, daily life

a 1 Leofwin’s world

a 2 Wordsnake

13 3 More on Leofwin’s world

74 4 ‘this’ — some grammar, and a test!

ie) 5 Leofwin’s daily routine

7 6 Tasks on daily routine

78 7 More on daily routine

80 8 Consolidation of verb patterns

83 9 Mini-essay: the Round of the Year

page 87 Leornungdeel 6 - mete, drenc and mé!l / food, drink and meals

1 Clufweart milks the cow

2 Food and drink vocabulary

3. Revision of plurals and checking of new vocabulary

4 (a) Foxtail talks about mealtimes

(b) Mealtimes — true, false or unknown

5 ‘drincan’, to drink and ‘etan’, to eat

6 More on mealtimes

7 Leofwin asks you about your mealtimes

8 Talking animals: translation

9 ‘niman’ to take, and ‘giefan’ to give

10 More food and drink vocabulary

11 Revise likes and dislikes

12 Revision of negatives

13. Leofwin describes Easter

14. Three new verbs — cooking, catching, answering

15 Belonging — possessive adjectives

16 Ealhstan’s Easter Sermon

17 Mini-essay — food and drink / cooking and eating

Vocabulary: New English (NE) to Old English(OE)

Vocabulary: Old English (OE) to New English (NE)

Transcripts and Answers

Grammar Summary

Foreword

Nearly ten per cent of the people on our planet speak English either as their mother tongue,

or as a first foreign language of choice. It’s a global language. But where did it come from?

How long has it been around? How much has it changed over time?

This book aims to give the reader who is not a language specialist a glimpse of the English

language as it was spoken over a thousand years ago by a couple of million people on a

green and pleasant island off the coast of mainland Europe.

Old English, as it is called, or Anglo-Saxon, survives in a fairly substantial number of

manuscripts, which include laws, charters, wills, histories, religious works, poetry,

medical and scientific treatises and other material. If everything were collected together,

it would take up the equivalent space of about forty or so medium-sized books. The

material dates from the 8" to the 11" century, during which time the language was

evolving constantly; it continues to do so today.

There are, of course, gaps, regional variations, and since what survives is necessarily rather

‘bookish’, there are some aspects of the everyday language which can only be inferred.

Nevertheless, it is this everyday language of Anglo-Saxon England that I’ve tried to present

in this book. Old English tends rather to be the playground of paleo-linguists and

philologists, who are interested primarily in how language changes over time and in the

relationship of languages to each other. Although there’s a fairly wide range of books on

Old English, many can appear rather intimidating and inaccessible to anyone who’s not

already heavily involved in this kind of study.

‘Leofwin’ presents Old English, as far as possible, as if it were a living language, and I

hope it will fill the need for a lively, entertaining and attractive introduction for anyone

interested in the roots of our quirky and marvellous tongue.

My thanks are due to David Cowley, who checked the draft text, and to Steve Pollington,

who put me up to the whole project. Also to Linden Currie, and my other friends in ‘The

English Companions’, who’ve given me every encouragement. To Maria Legg, who

provided all the female voices in the audio passages, and to the wonderful people of

‘Centingas’, who share my passion for Anglo-Saxon Living History. To my son Thomas,

for all his help with computer issues, and finally to Tony Linsell of Anglo-Saxon books,

for whose patience, support, guidance and gentle criticism I’m very grateful. Whatever

errors still lurk within these pages are, of course, my own responsibility.

MWL, Leigh-on-Sea, September 2012

Going Back in time - New English to Old English

Language never stops changing! New words are being born all the time, while others fade away.

The way we pronounce words changes slowly over time as well, while more slowly still we alter

the rules of our grammar. How hard will it be to learn the English spoken here more than a

thousand years ago?

1800

If you could travel back in time 200 years, you’d be able to understand the English spoken here in

England without any difficulty, although a few of the sounds and words might be just a little

unfamiliar at first. Because of Britain’s Empire, English is already a global language, spoken in

North America, the Caribbean, India, Australia, parts of Africa and elsewhere.

1600

Another 200 years back: this is the language of Shakespeare. It’s recognizably English, but with

many unfamiliar words and expressions. Printing has helped to ‘standardize’ the language, and lots

of Greek and Latin words are being brought in which we take for granted in the 21° century.

However, many words and some of the grammar seem strange. The language of this period is called

‘Early Modern English’.

1400

Now we’re back to medieval times. Printing hasn’t been invented yet, so all writing is done by

hand. The thousands of French words which flooded into English after the Norman Conquest of

1066 are still settling in to the language. The language sounds very different, and without studying

it, you’d find many words unrecognizable. The language of these times is called ‘Middle English’.

1200

There are two different languages being spoken in England. Norman-French is the language spoken

by the king, the court, and the upper classes, because of the Norman Conquest. English is spoken

by the English people, with just a few words beginning to be adopted from French. These are the

last generations to speak alate form of ‘Old English’. For 21“ century English-speakers, it’s virtually

a foreign language.

1000

Another 200 years back in time: the Battle of Hastings hasn’t yet been fought. Old English is

spoken across the length and breadth of England. Because of the efforts of King Alfred the Great,

many literary and religious texts have been translated into English, and it has become a language

capable of expressing sophisticated thought. Trade and cultural links across the North Sea, and the

settlement of Vikings in the east and north is playing a part in simplifying Old English. This book is

set in this period, in the late 900s.

800

As we go ever further back in time, it starts to grow difficult to find surviving documents in Old

English. There are several different English-speaking kingdoms across the land, often at war with

each other.

600

The English at this time are still fighting with the people who were here before they arrived — the

Britons. They’ve been coming from across the North Sea for a hundred and fifty years or so: in

particular from the areas known today as Angeln, Saxony, Jutland and Frisia. These times have

8