Table Of ContentJIMI HENDRIX

The Reverb series looks at the connections between music, artists and performers,

musical cultures and places. It explores how our cultural and historical understanding

of times and places may help us to appreciate a wide variety of music, and vice versa.

reverb-series.co.uk

Series editor: John Scanlan

Already published

The Beatles in Hamburg

Ian Inglis

Brazilian Jive: From Samba to Bossa and Rap

David Treece

Easy Riders, Rolling Stones: On the Road in America, from Delta Blues to ’70s Rock

John Scanlan

Heroes: David Bowie and Berlin

Tobias Rüther

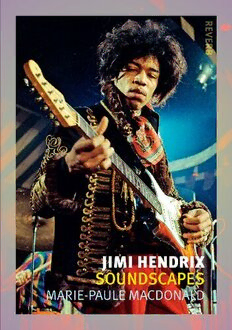

Jimi Hendrix: Soundscapes

Marie-Paule Macdonald

Neil Young: American Traveller

Martin Halliwell

Nick Drake: Dreaming England

Nathan Wiseman-Trowse

Remixology: Tracing the Dub Diaspora

Paul Sullivan

Tango: Sex and Rhythm of the City

Mike Gonzalez and Marianella Yanes

Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock’n’roll

John Scanlan

JIMI HENDRIX

SOUNDSCAPES

MARIE-PAULE MACDONALD

reaktion books

To Thérèse Ruest Lévesque and M. C. Bernadette Macdonald

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

44–48 Wharf Road

London n1 7ux, uk

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright © Marie-Paule Macdonald 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn 978 1 78023 530 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: EXTRATERRESTRIAL BLUES 7

1 WEST: VANCOUVER, SEATTLE, MONTEREY, SAN FRANCISCO,

LOS ANGELES 13

2 SOUTH: NASHVILLE, MEMPHIS, ATLANTA, NEW ORLEANS 63

3 EAST: HARLEM, NEW YORK, NEW JERSEY 83

4 LONDON: A PSYCHEDELIC SCENE 107

5 T HE NEW YORK–LONDON AXIS: A SERIES OF RETURNS 147

6 HEAVY TOURING 183

CONCLUSION 236

Chronology 243

References 253

Select Bibliography 285

Discography 291

Acknowledgements 293

Photo Acknowledgements 295

Index 297

INTRODUCTION: EXTRATERRESTRIAL BLUES

I want a big band . . . I mean a big band full of

competent musicians that I can conduct and write for. And

with the music we will paint pictures of earth and space,

so that the listener can be taken somewhere.

Jimi Hendrix, London, 5 September 19701

If an alien were to come down to study the American, European

and African cities and landscapes that Hendrix frequented, what

kind of impression would they make? What roles do urban and

architectural locations play in musical experience, in collective

meaning? The Vancouver-based science fiction writer William

Gibson said: ‘The future is already here – it’s just not very

evenly distributed.’2 Is the future embedded in sound and its

environments? That seems to be the case for the Hendrix sound,

which is so often described as a sound of the future.

Out of nowhere, and traversing boundaries, Hendrix was a

virtuoso guitarist who avidly refined his craft, and his influence

lives on in recordings, texts and imagery. There is consensus in

the collective perception that his legacy remains culturally fresh

and relevant. At first there was criticism that the mass reception

of his band’s music was primarily by a targeted white youth

market, but in 2010 the Pop Matters journalist Mark Reynolds

stated: ‘Hendrix has been claimed by the black mainstream as a

cultural innovator of the highest order.’3 With recent reworkings

of disciplinary barriers, classical musicians, as well as blues, rock,

rap and folk artists, admire and draw inspiration from Hendrix’s

sonic innovation and composition.

Just as there are many diverse audiences, so there are many

possible approaches to the work and legacy of Jimi Hendrix,

7

jimi hendrix

from biographical and historical to musicological or sociological,

to this contemporary perspective, informed by current, shifting

ideas about music, sound and media communication in our

technological society. This approach reflects on the particular

resonance of Hendrix and his influential performing and

recording career in terms of soundscape, environment, landscape,

place, geography and built form. It relates issues of location

to perceptions of digitally produced placeless sound and the

repercussions, in the Obama era, of an extended reception by

a mass audience listening for innovative sound.

The notion of soundscape, which varies with place and

climate, presents a frame for perceiving the aural textures that

Hendrix heard, invented, composed, edited and incorporated

into his guitar and recording vocabulary. In his formative years,

Hendrix lived in Seattle and Vancouver. His acoustic environment

was a moist soundscape whose keynote sound is the sound of

wood, in the words of the composer R. Murray Schafer, who

coined the term ‘soundscape’. The forested ocean-side climate

of the Pacific Northwest endures as a dampened, rained-on

mountainous landscape, often with a horizon of heavy cloud,

punctuated by a linear, continuous sound of running water.

Humour about the rainforest often invokes Noah.

Along with the environment-based notion of soundscape, the

conceptual framework for the history of the blues, no longer

constrained by state lines, has overflowed into bioregions.

Blues historians emphasize that the migration that defined the

lives of blues musicians was more sympathetic to geography:

lowlands; bottomlands; deltas or watersheds, like that of the

vast Mississippi River; smaller towns; crossroads; migration hubs

along rivers, railways or highways.4 William Gibson’s quip about

the distribution of the future could launch a riff on the places of

a particular time, in the manner of the literary theorist Mikhail

8

introduction: extraterrestrial blues

Bakhtin, whose notion of chronotope fused a cultural moment

and its location.5 The idea of long duration, or longue durée, in the

terminology of the historian Fernand Braudel, marks a parallel

approach to rooting events to specific locations.6 In the case of

Hendrix, the intensity of his migratory life introduced a new

paradigm, a meteoric, moveable geography of sound.

Hendrix emerged from a specific coastal environment, and

within that from a disparate set of homes. In his brief adult life he

moved constantly, from many different houses in the early years

in Seattle to many anonymous hotel rooms, then on to slightly

more personal recording studios and several apartments on two

continents. At the beginning of the twentieth century the

German architect Paul Scheerbart wrote: ‘We live for the most

part within enclosed spaces. These form the environment from

which our culture grows.’7 Hendrix roamed city streets. When

he did check into a lodging, he tended to stay inside the rooms,

practising guitar riffs, recording and dreaming sounds. With the

intense, sensual perception of a musical being, he digested his world

of sound, that is, of corporeal vibrations bouncing off immediate

surroundings, mingled with smells, humidity and illumination.

Hendrix’s body of work has been expanding continuously,

as its own particular universe. He was born at the very start of

the Second World War baby boom and was part of a generation

that gave rise to numerous youth movements and cultural

phenomena. The influence of his generation has begun to fade

even as his audience continues to grow. There is a continuing

lively business aspect: the album Valleys of Neptune charted at

number four in the United States in 2010, and that year Hendrix

sold more than a million albums altogether.8

In search of places to play music, Hendrix began performing

wherever he could, and as his notoriety grew he began to be

booked in both conventional and unconventional venues.

Part of the reason for this was the effect of the youth movement

9