Table Of ContentALSO BY JULIA CAMERON

BOOKS IN THE ARTIST’S WAY SERIES

The Artist’s Way

The Artist’s Way For Parents

(with Emma Lively) Walking in This World

Finding Water

The Complete Artist’s Way The Artist’s Way Workbook The Artist’s Way Every Day The Artist’s Way

Morning Pages Journal The Artist’s Date Book

(illustrated by Elizabeth Cameron) Inspirations: Meditations from The Artist’s Way

OTHER BOOKS ON CREATIVITY

The Prosperous Heart

(with Emma Lively) Prosperity Every Day

The Writing Diet

The Right to Write

The Sound of Paper

The Vein of Gold

How to Avoid Making Art (or Anything Else You Enjoy)

(illustrated by Elizabeth Cameron) Supplies: A Troubleshooting Guide for Creative Difficulties The

Writer’s Life: Insights from The Right to Write The Artist’s Way at Work

(with Mark Bryan and Catherine Allen) Money Drunk, Money Sober

(with Mark Bryan) The Creative Life

PRAYER BOOKS

Answered Prayers

Heart Steps

Blessings

Transitions

Prayers to the Great Creator

BOOKS ON SPIRITUALITY

Safe Journey

Prayers from a Nonbeliever Letters to a Young Artist God Is No Laughing Matter God Is Dog Spelled

Backwards

(illustrated by Elizabeth Cameron) Faith and Will

MEMOIR

Floor Sample: A Creative Memoir

FICTION

Mozart’s Ghost

Popcorn: Hollywood Stories The Dark Room

PLAYS

Public Lives

The Animal in the Trees

Four Roses

Love in the DMZ

Avalon (a musical) The Medium at Large (a musical) Magellan (a musical)

POETRY

Prayers for the Little Ones Prayers to the Nature Spirits The Quiet Animal

This Earth

(also an album with Tim Wheater) FEATURE FILM

(as writer-director) God’s Will

This book is dedicated to Jeremy Tarcher, whose lifelong creativity

inspired us all.

Contents

Also by Julia Cameron

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

WEEK ONE Reigniting a Sense of Wonder

WEEK TWO Reigniting a Sense of Freedom

WEEK THREE Reigniting a Sense of Connection

WEEK FOUR Reigniting a Sense of Purpose

WEEK FIVE Reigniting a Sense of Honesty

WEEK SIX Reigniting a Sense of Humility

WEEK SEVEN Reigniting a Sense of Resilience

WEEK EIGHT Reigniting a Sense of Joy

WEEK NINE Reigniting a Sense of Motion

WEEK TEN Reigniting a Sense of Vitality

WEEK ELEVEN Reigniting a Sense of Adventure

WEEK TWELVE Reigniting a Sense of Faith

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Index

Introduction

T

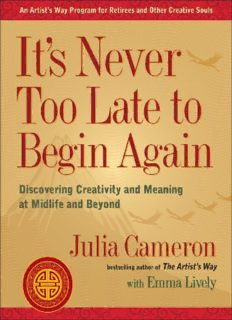

wenty-five years ago I wrote a book on creativity called The Artist’s

Way. It spelled out, in a step-by-step fashion, just what a person could

do to recover—and exercise—their creativity. I often called that book

“The Bridge” because it allowed people to move from the shore of

their constrictions and fears to the promised land of deeply fulfilling creativity.

The Artist’s Way was used by people of all ages, but I found my just-retired

students the most poignant. I sensed in them a particular problem set that came

with maturity. Over the years, many of them asked me for help dealing with

issues specific to transitioning out of the work force. The book you hold in your

hands is the distillate of a quarter century’s teaching. It is my attempt to answer,

“What next?” for students who are embarking on their “second act.” In this book

you will find the common problems facing the newly retired: too much time,

lack of structure, a sense that our physical surroundings suddenly seem outdated,

excitement about the future coupled with a palpable fear of the unknown. As a

friend of mine worried recently, “All I do is work. When I stop working, will I

do . . . nothing?”

The answer is no. You will not do “nothing.” You will do many things. You

will be surprised and delighted by the well of colorful inspiration that lies within

you—a well that you alone can tap. You will discover that you are not alone in

your desires, and that there are creativity tools that can help you navigate the

specific issues of retirement. Those who worked the Artist’s Way will find some

of the tools familiar. Other tools are new, or their use is innovative. This book

attempts to address many taboo subjects for the newly retired: boredom,

giddiness, a sense of being untethered, irritability, excitement, and depression, to

name just a few. It seeks to give its practitioners a simple set of tools that, used

in combination, will trigger a creative rebirth. It attempts to prove that everyone

is creative—and that it is never too late to explore your creativity.

When my father entered retirement after a busy and successful thirty-five

years as an account executive in advertising, he turned to nature. He acquired a

black Scottie dog named Blue that he took for long, daily walks. He also

acquired a pair of birding binoculars and found that the hourly tally of winged

friends brought him wonder and joy. He spotted finches, juncos, chickadees,

wrens, and more exotic visitors, like egrets. He lived half the year on a sailboat

in Florida and half the year just outside of Chicago. He enjoyed the differing

bird populations and was enchanted by their antics. When it got too dangerous

for him to live alone on his boat, he moved to the north permanently, settling

into a small cottage on a lagoon. There he spotted cardinals, tanagers, blue jays,

owls, and the occasional hawk. When I would visit him, he would share his love

of birding. His enthusiasm was contagious, and I found myself buying Audubon

prints of the birds my father was spotting. Mounted and carefully framed, the

prints brought me much joy. My father’s newfound hobby soon became my own,

if only in snatches.

“It just takes time and attention,” my dad would say. Retired, he found he had

both. The birds kept my father company. He was thrilled when a great blue

heron established a nest within his view. Visiting my father, I would always

hope for a glimpse. The herons were lovely and elegant. My father waited for

them patiently. His patience was a gift of his retirement. During his high-

powered and stress-filled career, he had no dog and no birds. But nature had

called to him, and it was a call he was only able to respond to fully once he

retired.

At age fifty-four, I moved to Manhattan. At age sixty-four, entering my own

seniority, I moved to Santa Fe. I knew two people who lived in Santa Fe: Natalie

Goldberg, the writing teacher, and Elberta Honstein, who raised champion

Morgan horses. It could be argued that I had my two most important bases

covered. I loved writing and I loved horses. In my ten years in Manhattan, I had

written freely, but I didn’t ride. It was an Artist’s Way exercise that moved me to

Santa Fe. I had made a list of twenty-five things that I loved, and high on that list

were sage, chamisa, juniper, magpies, red-winged blackbirds, and big skies. In

short, a list of the Southwest. Nowhere on the list did New York put in an

appearance. No, my loves were all Western flora and fauna: deer, coyotes,

bobcats, eagles, hawks. I didn’t think about my age when I made my list,

although I now realize that the move from New York to Santa Fe might be my

last major move.

Allotting myself three days to find a place to live, I flew from New York to

Santa Fe and began hunting. I made a list of everything I thought I wanted: an

apartment, not a house; walking distance to restaurants and coffee shops;

mountain views. The first place the Realtor showed me had every single trait on

my list, and I hated it. We moved on, viewing listing after listing. Many of the

rentals featured pale carpeting, and I knew from my years in Taos that such

carpeting was an invitation for disaster.

Finally, late on my first day of hunting, my Realtor drove us to a final house.

“I don’t know why I’m showing you this,” she began, winding her way

through a maze of dirt roads to a small adobe house with a yard strewn with

toys. “A woman with four children lives here,” she apologized. I peered into the

house. Toys and clothing were strewn every which way. Couches were shoved

chockablock.

“I’ll take it,” I told my startled Realtor. The house was nestled among juniper

trees. It had no mountain views. It was miles from restaurants and cafés. Yet, it

shouted “home” to me. Its steep driveway would be treacherous in winter, and I

sensed that I would have to become accustomed to being snowbound. But it also

featured a windowed, octagonal room surrounded by trees. I knew my father

would have loved this “bird room.” I made it my writing room, and I have

appreciated my daily dose of aviary enlightenment every day that I have lived

here.

I have lived in this adobe house halfway up the mountain for almost three

years now, collecting books and friends. Santa Fe has proven to be hospitable. It

is a town full of readers, where my work is appreciated. Often, I am recognized

from my dust jacket photo. “Thank you for your books,” people say. I put my

life in Santa Fe together in a painstaking way. My friendships are grounded in

common interests. I myself believe creativity is a spiritual path, and my friends

number many Buddhists and Wiccans among them. Every three months, I go

back to Manhattan, where I teach workshops. The city feels welcoming but

overwhelming. I identify myself to my students as “Julia from Santa Fe.” I love

living there, I tell them, and it’s true.

My mail comes to a rickety mailbox at the foot of my drive. I have to force

myself to open the mailbox and retrieve it. So much of what I receive is

unwelcome. In March of my first year in Santa Fe, I turned sixty-five. But it was

in January that my mail became infested with propaganda related to aging.

Daily, I would receive notices about Medicare and special insurance targeting

me as a senior. The mail felt intrusive, as if I were being watched. Just how,

precisely, did the many petitioners know that I was turning sixty-five?

I found myself dreading my birthday. I might have felt young at heart, yet I

was officially categorized as a senior. The mail went so far as to solicit my

payment on a gravesite. Clearly I was not only aging, I was nearing the end of

my life. Did I want my family saddled with burial costs? No, I did not.

The mail became a mirror that reflected me back in a harsh and unforgiving

light. My laugh lines became wrinkles. My throat displayed creases. I thought of

Nora Ephron’s memoir I Feel Bad About My Neck. When first I read it at sixty, I

thought it was melodramatic. But that was before I felt bad about my own neck,

before I turned sixty-five and became a certified elder.

The term “senior” officially applies to those sixty-five and older. But not

everyone who is called a senior feels like a senior. And not everyone who retires

is sixty-five. Some retire at fifty, some at eighty. Age is a relative thing. Most

working artists never retire. As director John Cassavetes put it, “No matter how

old you get, if you can keep the desire to be creative, you’re keeping the man-

child alive.” Cassavetes himself was a fine example of what might be called

“youthful aging.” He both acted and directed, making and attending films that

reflected his own convictions. Working with an ensemble of actors that included

his wife, Gena Rowlands, he told tales of intimacy and connection. As he aged,

Cassavetes cast himself in his films, portraying troubled and conflicted men. His

passion was palpable. Even if he played the oldest character in the movie, he was

always young at heart. Taking a cue from Cassavetes, we can retain a passionate

interest in life. We can throw ourselves wholeheartedly into projects. At sixty-

five, we can still be vibrant beginners.

I’m told the median age in Santa Fe is sixty. It’s true that when I go grocery

shopping I note many elders pushing carts. People retire to Santa Fe. I have

almost become used to the question, “Are you still writing?” The truth is, I

cannot imagine not writing. I go from project to project, always frightened by

the gap in between. I catch myself distrusting my own process. No matter that I

have forty-plus books to my credit, I am afraid that each book will be my last,

that I will finally be stymied by age.

Recently, I went to talk to Barbara McCandlish, a gifted therapist.

“I’m sad,” I told her. “I’m afraid I’ll never write again.”

“I think you’re afraid of aging,” said Barbara. “I think if you write about that,

you’ll find yourself writing freely again.”

The answer is always creativity.

Theater playwright Richard Nelson throws himself into new projects. His age

is not an issue. One of his more recent works, the theatrical cycle The Apple

Family Plays, sets an example of just what is possible with commitment.

Excellent writer John Bowers published his first novel, End of Story, at age

sixty. At age sixty-four, he is hard at work on a second novel, longer and more

ambitious than his first—and he’s quick to remark that Laura Ingalls Wilder

published Little House in the Big Woods when she was sixty-four. John opened

his recent book signing in Santa Fe by remarking that the bright stage lights

revealed his many wrinkles. An attractive man, he carries his age lightly—