Table Of ContentDEDICATION

To Sarah

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 Divine Humans in Ancient Greece and Rome

2 Divine Humans in Ancient Judaism

3 Did Jesus Think He Was God?

4 The Resurrection of Jesus: What We Cannot Know

5 The Resurrection of Jesus: What We Can Know

6 The Beginning of Christology: Christ as Exalted to Heaven

7 Jesus as God on Earth: Early Incarnation Christologies

8 After the New Testament: Christological Dead Ends of the Second and Third

Centuries

9 Ortho-Paradoxes on the Road to Nicea

EPILOGUE: Jesus as God: The Aftermath

NOTES

SCRIPTURE INDEX

SUBJECT AND AUTHOR INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY BART D. EHRMAN

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I

WOULD LIKE TO ACKNOWLEDGE the scholars who have assisted me by reading an

earlier draft of this book and providing extensive and helpful comments. If

everyone had such insightful and generous friends and colleagues, the world

would be a much happier place. My readers have been Maria Doerfler, a

remarkable and wide-ranging scholar just now starting to teach church history as

an assistant professor at Duke Divinity School; Joel Marcus, professor of New

Testament at Duke Divinity School, who for nearly thirty years has generously

read my work and consistently spilled lots of red ink all over it; Dale Martin,

professor of New Testament at Yale, my oldest friend and colleague in the field,

whose critical insights have for very many years helped shape me as a scholar;

and Michael Peppard, assistant professor of New Testament at Fordham

University, whom I have only recently come to know and who has written a

book, which I cite in the course of my study, that had a significant effect on my

thinking.

I also thank the entire crew at HarperOne, especially Mark Tauber,

publisher; Claudia Boutote, associate publisher; Julie Baker, my talented and

energetic publicist; and above all Roger Freet, my perceptive and unusually

helpful editor, who has helped make this a better book.

I am dedicating the book to my brilliant and scintillating wife, Sarah

Beckwith. I dedicated another book to her years ago, but since I continuously

rededicate my life to her, I think it is time to rededicate a book to her. She is the

most amazing person I know.

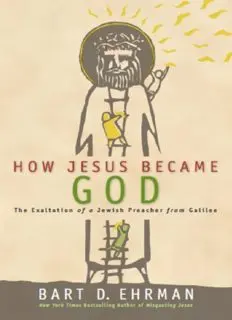

INTRODUCTION

J

ESUS WAS A LOWER-CLASS Jewish preacher from the backwaters of rural Galilee

who was condemned for illegal activities and crucified for crimes against the

state. Yet not long after his death, his followers were claiming that he was a

divine being. Eventually they went even further, declaring that he was none

other than God, Lord of heaven and earth. And so the question: How did a

crucified peasant come to be thought of as the Lord who created all things? How

did Jesus become God?

The full irony of this question did not strike me until recently, when I was

taking a long walk with one of my closest friends. As we talked, we covered a

number of familiar topics: books we had been reading, movies we had seen,

philosophical views we were thinking about. Eventually we got around to talking

about religion. Unlike me, my friend continues to identify herself as a Christian.

At one point, I asked her what she considered to be the core of her beliefs. Her

answer gave me pause. She said that, for her, the heart of religion was the idea

that in Jesus, God had become a man.

One of the reasons I was taken aback by her response was that this used to be

one of my beliefs as well—even though it hasn’t been for years. As far back as

high school, I had pondered long and hard this “mystery of faith,” as found, for

example, in John 1:1–2, 14: “In the Beginning was the Word, and the Word was

with God, and the Word was God. . . . And the Word became flesh and dwelt

among us, and we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the

Father.” Even before that, I had openly and wholeheartedly confessed the

Christological statements of the Nicene Creed, that Christ was

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven;

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary,

and was made man.

But I had changed over the years, and now in middle age I am no longer a

believer. Instead, I am a historian of early Christianity, who for nearly three

decades has studied the New Testament and the rise of the Christian religion

from a historical perspective. And now my question, in some ways, is the precise

opposite of my friend’s. As a historian I am no longer obsessed with the

theological question of how God became a man, but with the historical question

of how a man became God.

The traditional answer to this question, of course, is that Jesus in fact was

God, and so of course he taught that he was God and was always believed to be

God. But a long stream of historians since the late eighteenth century have

maintained that this is not the correct understanding of the historical Jesus, and

they have marshaled many and compelling arguments in support of their

position. If they are right, we are left with the puzzle: How did it happen? Why

did Jesus’s early followers start considering him to be God?

In this book I have tried to approach this question in a way that will be useful

not only for secular historians of religion like me, but also for believers like my

friend who continue to think that Jesus is, in fact, God. As a result, I do not take

a stand on the theological question of Jesus’s divine status. I am instead

interested in the historical development that led to the affirmation that he is God.

This historical development certainly transpired in one way or another, and what

people personally believe about Christ should not, in theory, affect the

conclusions they draw historically.

The idea that Jesus is God is not an invention of modern times, of course. As

I will show in my discussion, it was the view of the very earliest Christians soon

after Jesus’s death. One of our driving questions throughout this study will

always be what these Christians meant by saying “Jesus is God.” As we will see,

different Christians meant different things by it. Moreover, to understand this

claim in any sense at all will require us to know what people in the ancient world

generally meant when they thought that a particular human was a god—or that a

god had become a human. This claim was not unique to Christians. Even though

Jesus may be the only miracle-working Son of God that we know about in our

world, numerous people in antiquity, among both pagans and Jews, were thought

to have been both human and divine.

It is important already at this stage to stress a fundamental, historical point

about how we imagine the “divine realm.” By divine realm, I mean that “world”

that is inhabited by superhuman, divine beings—God, or the gods, or other

superhuman forces. For most people today, divinity is a black-and-white issue. A

being is either God or not God. God is “up there” in the heavenly realm, and we

are “down here” in this realm. And there is an unbridgeable chasm between

these two realms. With this kind of assumption firmly entrenched in our

thinking, it is very hard to imagine how a person could be both God and human

at once.

Moreover, when put in these black-and-white terms, it is relatively easy to

say, as I used to say before doing the research for this book, that the early

Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke—in which Jesus never makes explicit

divine claims about himself—portray Jesus as a human but not as God, whereas

the Gospel of John—in which Jesus does make such divine claims—does indeed

portray him as God. Yet other scholars forcefully disagree with this view and

argue that Jesus is portrayed as God even in these earlier Gospels. As a result,

there are many debates over what scholars have called a “high Christology,” in

which Jesus is thought of as a divine being (this is called “high” because Christ

originates “up there,” with God; the term Christology literally means

“understanding of Christ”) and what they have called a “low Christology,” in

which Jesus is thought of as a human being (“low” because he originates “down

here,” with us). Given this perspective, in which way is Jesus portrayed in the

Gospels—as God or as human?

What I have come to see is that scholars have such disagreements in part

because they typically answer the question of high or low Christology on the

basis of the paradigm I have just described—that the divine and human realms

are categorically distinct, with a great chasm separating the two. The problem is

that most ancient people—whether Christian, Jewish, or pagan—did not have

this paradigm. For them, the human realm was not an absolute category

separated from the divine realm by an enormous and unbridgeable crevasse. On

the contrary, the human and divine were two continuums that could, and did,

overlap.

In the ancient world it was possible to believe in a number of ways that a

human was divine. Here are two major ways it could happen, as attested in

Christian, Jewish, and pagan sources (I will be discussing other ways in the

course of the book):

By adoption or exaltation. A human being (say, a great ruler or warrior or

holy person) could be made divine by an act of God or a god, by being

elevated to a level of divinity that she or he did not previously have.

By nature or incarnation. A divine being (say, an angel or one of the

gods) could become human, either permanently or, more commonly,

temporarily.

One of my theses will be that a Christian text such as the Gospel of Mark

understands Jesus in the first way, as a human who came to be made divine. The

Gospel of John understands him in the second way, as a divine being who

became human. Both of them see Jesus as divine, but in different ways.

Thus, before discussing the different early Christian views of what it meant

to call Jesus God, I set the stage by considering how ancient people understood

the intersecting realms of the divine and the human. In Chapter 1 I discuss the

views that were widely held in the Greek and Roman worlds outside both

Judaism and Christianity. There we will see that indeed a kind of continuum

within the divine realm allowed some overlap between divine beings and

humans—a matter of no surprise for readers familiar with ancient mythologies in

which the gods became (temporarily) human and humans became (permanently)

gods.

Somewhat more surprising may be the discussion of Chapter 2, in which I

show that analogous understandings existed even within the world of ancient

Judaism. This will be of particular importance since Jesus and his earliest

followers were thoroughly Jewish in every way. And as it turns out, many

ancient Jews, too, believed not only that divine beings (such as angels) could

become human, but that human beings could become divine. Some humans were

actually called God. This is true not only in documents from outside the Bible,

but also—even more surprising—in documents within it.

After I have established the views of both pagans and Jews, we can move in

Chapter 3 to consider the life of the historical Jesus. Here my focus is on the

question of whether Jesus talked about himself as God. It is a difficult question

to answer, in no small measure because of the sources of information at our

disposal for knowing anything at all about the life and teachings of Jesus. And so

I begin the chapter by discussing the problems that our surviving sources—

especially the Gospels of the New Testament—pose for us when we want to

know historically what happened during Jesus’s ministry. Among other things, I