Table Of ContentAlso in the Yale English Monarchs Series

ATHELSTAN by Sarah Foot

EDWARD THE CONFESSOR by Frank Barlow

WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR by David Douglas*

WILLIAM RUFUS by Frank Barlow

HENRY I by Warren Hollister

KING STEPHEN by Edmund King

HENRY II by W. L. Warren*

RICHARD I by John Gillingham

KING JOHN by W. L. Warren*

EDWARD I by Michael Prestwich

EDWARD II by Seymour Phillips

RICHARD II by Nigel Saul

HENRY V by Christopher Allmand

HENRY VI by Bertram Wolffe

EDWARD IV by Charles Ross

RICHARD III by Charles Ross

HENRY VII by S. B. Chrimes

HENRY VIII by J. J. Scarisbrick

EDWARD VI by Jennifer Loach

MARY I by John Edwards

JAMES II by John Miller

QUEEN ANNE by Edward Gregg

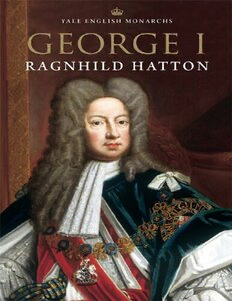

GEORGE I by Ragnhild Hatton

GEORGE II by Andrew C. Thompson

GEORGE III by Jeremy Black

GEORGE IV by E. A Smith

* Available in the U. S. from University of California Press

For Harry, who had a Hanoverian great-grandmother

First published in 1978 by Thames and Hudson Ltd

This edition first published by Yale University Press in 2001

Copyright © 1978 Thames and Hudson

New Edition © 2001 Peter S. Hatton and Paul G. Hatton

New Foreword © 2001 Jeremy Black

Library of Congress Control Number: 2001087415

ISBN 0–300–08883–3 (pbk.)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund

Contents

FOREWORD TO THE YALE EDITION (by Jeremy Black)

PREFACE

SPELLING OF NAMES AND PLACES

NOTE ON DATES

I Parents and childhood

II The electoral cap

The father's plans for his son

The family's advancement and George's marriage

The primogeniture struggle

George's divorce

III Experience gained

The Königsmarck myth

George at the helm

The prospect of England

Struggle over the English succession between George and his mother

Wider German horizons

Losses of friends and companions

IV The royal crown

Hanover and Celle united

George's household after 1698

The War of the Spanish Succession

Death of queen Anne: the ‘Act of Settlement’ put into effect

V Settling down

Great Britain at the time of George's accession

George and the party system

The king's English

The royal household

VI Two issues of principle

The struggle for place and profit

Promotion by title

The Hanoverian succession

VII Three crises

George I's image

The Jacobite ‘Fifteen’

European issues 1716–17

The ministerial crisis

Quarrel in the royal family

VIII The watershed 1718–21

Lessons learnt

European peace plans

Success in the south

Partial success in the north

Shifts of emphasis

IX Peace, its problems and achievements

The South Sea bubble

George, a captive of his ministers?

George as a patron of the arts

Unfinished business

Alliances and counter-alliances

War or peace?

X Death of George I

George's last journey

The balance sheet

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES TO THE TEXT

GENEALOGICAL TABLES

MAP 1: George's Hanoverian dominions and the near neighbours of his electorate

MAP 2: Northern Europe

MAP 3: Southern Europe

INDEX

FOREWORD TO THE YALE EDITION

by Jeremy Black

George I: Elector and King appeared shortly before the end of Ragnhild Hatton's

distinguished career at the London School of Economics. It was published in 1978 by Thames

and Hudson (in the United Kingdom), Harvard University Press (in the United States), and,

appropriately, in German as George I: Ein deutscher Kurfürst auf Englands Thron, by

Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt. The biography amply justified that often clichéd term, ‘the

culmination of a lifetime's study’, because Hatton's first book, her thesis published in 1950,

had covered a central topic in British foreign policy during George's initial seven years as

king. Hatton's biography also consolidated her expertise as a biographer. She had published a

major life of Charles XII of Sweden (1968) as well as a number of studies of Louis XIV that,

while not amounting to a complete biography, nevertheless showed her acute understanding of

the monarch both as an individual and in the context of his times.1

Writing a biography of George I was a formidable challenge. Founder of the Hanoverian

dynasty in Britain, he was very much both elector of Hanover and king. As a consequence he

had partly eluded other British historians who lacked Hatton's interest in, deep knowledge of,

and appreciation of Continental power politics and Hanoverian concerns. J.H. Plumb's The

First Four Georges, for example, first published in 1956 and reissued, uncorrected, as late as

2000, included many of the standard, but erroneous judgements of an earlier age. Whereas

Plumb was definite that Sophia Charlotte, countess of Darlington was George's mistress,

Hatton had demonstrated that she was his half-sister, that she was devoted to her own husband,

and that incest was never imputed to George by anyone close to the royal circle.

Hatton's George was a ruler and a person in his contemporary European context, and her

study was based on extensive and wide-ranging archival research. She was interested in

people (alive as well as dead) and successfully sought to discover George as an individual, to

probe his relations with his parents and (unfaithful) spouse, with his mistress, his children, and

his courtiers and ministers. In place of a militaristic dolt, George was presented as a more

complex individual, with cultural and intellectual interests, and he was located in terms of the

Early Enlightenment.

All of these features justifiably earned Hatton high praise, and they emerge clearly from a

reading of her book.2 This introduction seeks to offer an updating that focuses on perspectives

suggested by subsequent work, and also tries to explain why George was less popular with his

British subjects than the above account might imply.

Subsequent research has not challenged Hatton's valuable account of George as elector, nor

her clear and well-grounded discussion of the international relations of his reign that provided

much of the dynamic for his policies. Hatton was very good on the House of Brunswick and its

position in Europe. Indeed the measure of her achievement stands even clearer as a result of