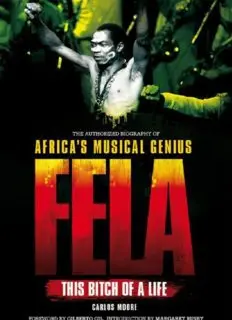

Table Of ContentCopyright © 2009 by Carlos Moore

Forward © 2009 by Gilberto Gil

Introduction © by Margaret Busby

Original © 1982 by Carlos Moore as Fela, Fela: cette putain de vie (Paris:

Khartala).

Published in English in 1982 as Fela, Fela: This Bitch Of A Life (London:

Allison and Busby).

English translation © 1982 by Allison and Busby

This edition © 2011 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-589-7

Cover designed by Fresh Lemon

Photographs © by individual photographers (André Bernabé, Chico, Donald

Cox, Bernard Matussière, Raymond Sardaby) and Fela Kuti, Fela Kuti

Collection.

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this

work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by

any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer

who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in

this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the

photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories,

visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit

www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Contents

Information Page

Foreword by Gilberto Gil

A Note from the Author

Introduction by Margaret Busby

Discography

1 Abiku: The Twice-Born

2 Three Thousand Strokes

3 Funmilayo: “Give Me Happiness”

4 Hello, Life! Goodbye, Daudu

5 J.K. Braimah: My Man Fela

6 A Long Way From Home

7 Remi: The One with the Beautiful Face

8 From Highlife Jazz to Afro-Beat: Getting My Shit

Together

9 Lost and Found in the Jungle of Skyscrapers

10 Sandra: Woman, Lover, Friend

11 The Birth of Kalakuta Republic

12 J.K. Braimah: The Reunion

13 Alagbon Close: “Expensive Shit”, “Kalakuta Show”,

“Confusion”

14 From Adewusi to Obasanjo

15 The Sack of Kalakuta: “Sorrow, Tears and Blood”,

“Unknown Soldier”, “Stalemate”

16 Shuffering and Shmiling: “ITT”, “Authority Stealing”

17 Why I Was Deported from Ghana: “Zombie”, “Mr

Follow Follow”, “Fear Not for Man”, “V.I.P.”

18 My Second Marriage

19 My Queens

20 What Woman is to Me: “Mattress”, “Lady”

21 My Mother’s Death: “Coffin for Head of State”

22 Men, Gods and Spirits

23 This Motherfucking Life

Epilogue: Rebel with a Cause

Foreword

Gilberto Gil

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, August 18, 2008

Africa, with her many peoples and cultures, is where the tragicomedy of the

human race first fatefully presented itself, wearing a mask at once beautiful and

horrendous. The Motherland, the cradle of civilization, acknowledged as the

original birthplace of us all, where the body and soul of mankind sank earliest

roots into the soil—Africa is, confoundingly, also the most reviled, wounded,

and disinherited of continents. Africa, treasure trove of fabulous material and

symbolic riches that throughout history have succored the rest of the world, is

yet the terrain that witnesses the greatest hunger ever, for bread and for justice.

This is the scenario into which Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Africa’s most recent

genius, emerged and struggled.

I was privileged to meet Fela in 1977 in his own musical kingdom, the Shrine,

a club located in one of Lagos’s lively working-class neighborhoods. It was

during the Second Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture (FESTAC),

and on that evening the great Stevie Wonder was also visiting.

Fela was the brilliant incarnation of Africa’s tragic dimension. He was an

authentic contemporary African hero whose genius was to make his scream

heard in every corner of the globe. Through his art, his wisdom, his politics, his

formidable vigor and love of life, he managed to rend the stubborn veil that

marginalizes “Otherness.” Deeply torn between the imperative of rejecting a

legacy of subordination and the need to affirm a new libertarian future for his

land and people, Fela ended up creating a body of work that is incomparable in

terms of international popular music that expresses the cosmopolitan—and

“cosmopolitical”—spirit of the second half of the twentieth century.

Fela was possessed by an apocalyptic vision, wherein he saw how tall were the

walls that had to be broken down. Thus, he engaged in a messianic rebellion. He

was enthralled by the haunting lamentations that emerged from the diaspora of

uprooted black slaves, reminding him of his own outraged sense of deracination

in his native Africa—a land increasingly usurped by neocolonial self-interest. He

was divided between the awareness that a universal future for all mankind was

inevitable and the awareness that there was danger in denying Africa its own

place in that future. Therefore he determined to rescue, both for his own people

and for the world, the wise traditions of tribal Africa, having in mind that we

might one day constitute a global tribe.

Arming himself with a Saxon horn—a saxophone—Fela made music that

harked back to days of yore, when his forebears were warriors and cattle herders.

Yet putting into the balance his virtuoso improvisation, his poetic outbursts, he

made everyone swing: in the Shrine, in the whole of Lagos, in every reservation,

in every shantytown, in every township of the black planet.

Today, some time after his passing, we are at a juncture at which we recognize

and acknowledge Fela’s work. But we must confer another form of

acknowledgment, one that goes beyond the careful, reverential attention that,

increasingly, is afforded his music—an acknowledgment in a wider intellectual

sense: one rooted in a careful analytical interpretation of what Fela and his work

stood for.

This book is among those that are aiming to fulfill that mandate.

At a time when, all over the world, we are engaged in the huge and (who

knows?) perhaps final effort to establish a viable humanist legacy for the

generations still to come—in an era that I may call posthuman—it is

indispensable to be able to rely on books that bestow on those efforts a true

dimension of legacy.

We need books that will tell us, now and here, and that later on will also tell the

builders of posthumankind, about those notable men and women of our recent

past, such as Fela Anikulapo-Kuti.

We need to know who they were and what they were about and how they have

enriched us.

Translated from the Portuguese by Tereza Burmeister

A Note from the Author

Originally published in France in 1982 as Cette putain de vie (This Bitch of a

Life), this book was born of a deep friendship with Fela and could not have been

written in the first person without his unreserved trust. He never intruded in the

work and allowed me full access to his personal files and domestic intimacy. I

thank him; his senior wife, the late Remi Taylor; his cowives; and those

members of his organization who assisted me in gathering the material for the

book: J. K. Braimah, Mabinuori Kayode Idowu (aka ID), Durotimi Ikujenyo

(aka Duro), and bandleader Lekan Animashaun. I am also grateful to Sandra

Izsadore, Fela’s longtime friend, for her generous assistance.

Writing the life story of someone else in the first person, then translating it into

another language, are tricky and perilous tasks. I succeeded only thanks to

Shawna Davis, who transcribed and edited the more than fifteen hours of tape-

recorded interviews that served as the building blocks for the original version,

then translated the manuscript into English. Her involvement was particularly

important in the two opening chapters, “Abiku” and “Three Thousand Strokes,”

and she contributed the descriptive biographical presentations of all those

interviewed, as well as the general introduction to chapter 19, “My Queens”

(where for the first time Fela’s wives expressed themselves). Without Shawna’s

rewriting and translation skills, and keen eye for the artistic, Fela: This Bitch of

a Life would have been a much different and certainly less attractive book. My

debt to her is immense.

Gratitude is also due to Nayede Thompson, who assisted Shawna with the

transcription and early drafts. I am beholden to the late Ellen Wright—former

literary agent and widow of Richard Wright—for having read the original

manuscript and made pertinent suggestions, as did Marcia Lord, whose feedback

was greatly valued.

In addition, I acknowledge the generous assistance of André Bernabé,

Heriberto Cuadrado Cogollo, and Donald Cox, whose photos, drawings, and

newspaper collages helped create the proper mood for Fela’s story.

This book owes a lot to Margaret Busby, who published the first English

edition of the book in 1982. Befittingly, twenty-seven years later she has written

the introduction to this new edition. I thank her dearly.

I am especially grateful to Gilberto Gil for undertaking to write the foreword

and to Stevie Wonder, Hugh Masekela, Randy Weston, and Femi Kuti for their

commentaries.

My literary agent, Janell Agyeman, and Lawrence Hill Books senior editor

Susan Bradanini Betz worked hard toward the agreement that has finally made

Fela’s life story, told in his own words, available to the public once more, and

for the first time in the United States.