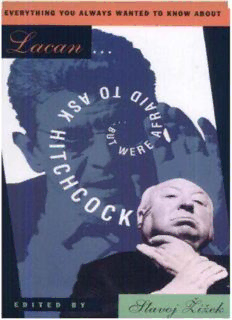

Table Of ContentEverything You Always Wanted

to Know about Lacan

(But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock)

V

Everything You Always

Wanted to Know about

Lacan (But Were Afraid to

Ask Hitchcock)

Edited by

SLAVOJ ZIZEK

V

VERSO

London • New York

First published by Verso 1992

© Verso 1992

Individual chapters © contributors

All rights reserved

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London Wl V 3HR

USA: 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001-2291

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN 0-86091-394-5

ISBN 0-86091-592-1 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Baskerville by Leaper & Gard Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Biddies Ltd, Guildford and Kings Lynn

Contents

INTRODUCTION Alfred Hitchcock, or, The Form and its

Historical Mediation Slavoj %iz.ek 1

PART I The Universal: Themes

'1 Hitchcockian Suspense Pascal Bonitzer 15

2 Hitchcock's Objects MladenDolar 31

• 3 Spatial Systems in North by Northwest Fredric Jameson 47

4 A Perfect Place to Die: Theatre in Hitchcock's Films

Alenka ^upancic 73

5 Punctum Caecum, or, Of Insight and Blindness

Stojan Pelko 106

PART II The Particular: Films

/l Hitchcockian Sinthoms Slavoj Zifek 125

2 The Spectator Who Knew Too Much MladenDolar 129

•3 The Cipher of Destiny Michel Chion 137

-4 A Father Who Is Not Quite Dead MladenDolar 143

5 Notorious Pascal Bonitzer 151

6 The Fourth Side Michel Chion 155

7 The Man Behind His Own Retina Miran Bofovic 161

8 The Skin and the Straw Pascal Bonitzer 178

V

9 The Right Man and the Wrong Woman Renata Salecl

10 The Impossible Embodiment Michel Chion

PART III The Individual: Hitchcock's Universe

'In His Bold Gaze My Ruin Is Writ Large' Slavoj Qzek

What's wrong with The Wrong Man ? • The

Hitchcockian allegory • From I to a • Psycho's

Moebius band • Aristophanes reversed • 'A triumph

of the gaze over the eye' • The narrative closure and

its vortex • The gaze of the Thing • 'Subjective

destitution' • The collapse of intersubjectivity

Notes on the Contributors

Index

vi

Sources

Pascal Bonitzer's 'Hitchcockian Suspense' was first published in

Cahiers du cinema no. 8 hors-serie; Michel Chion's 'The Cipher of

Destiny' was first published in Cahiers du cinema, no. 358, April 1984;

Pascal Bonitzer's 'Notorious' was first published in Cahiers du cinema

no. 309, 1980; Michel Chion's 'The Fourth Side' was first published

in Cahiers du cinema, no. 356, February 1984; Pascal Bonitzer's 'The

Skin and the Straw' was first published in L'Ane, no. 17, July-

August 1984; Michel Chion's 'The Impossible Embodiment' was

first published in his La Voix au cinema, Cahiers du cinema/Etoile

1982. Thanks are due to the copyright holders for permission to

reproduce them here. All appear for the first time in English and are

here translated by Martin Thorn.

vii

INTRODUCTION

Alfred Hitchcock, or, The Form

and its Historical Mediation

SLAVOJ 2I2EK

What is usually left unnoticed in the multitude of attempts to inter

pret the break between modernism and postmodernism is the way

this break affects the very status of interpretation. Both modernism and

postmodernism conceive of interpretation as inherent to its object:

without it we do not have access to the work of art — the traditional

paradise where, irrespective of his/her versatility in the artifice of

interpreting, everybody can enjoy the work of art, is irreparably lost.

The break between modernism and postmodernism is thus to be

located within this inherent relationship between the text and its

commentary. A modernist work of art is by definition 'incompre

hensible'; it functions as a shock, as the irruption of a trauma which

undermines the complacency of our daily routine and resists being

integrated into the symbolic universe of the prevailing ideology;

thereupon, after this first encounter, interpretation enters the stage

and enables us to integrate this shock - it informs us, say, that this

trauma registers and points towards the shocking depravity of our

very 'normal' everyday lives In this sense, interpretation is the

conclusive moment of the very act of reception: T.S. Eliot was quite

astute when he supplemented his Waste Land with notes on literary

references such as one would expect from an academic

commentary.

What postmodernism does, however, is the very opposite: its

objects par excellence are products with a distinctive mass appeal

(films like Blade Runner, Terminator or Blue Velvet) - it is for the

l

INTRODUCTION

interpreter to detect in them an exemplification of the most esoteric

theoretical finesses of Lacan, Derrida or Foucault. If, then, the

pleasure of the modernist interpretation consists in the effect of

recognition which 'gentrifies' the disquieting uncanniness of its

object ('Aha, now I see the point of this apparent mess!'), the aim of

the postmodernist treatment is to estrange its very initial homeli

ness: 'You think what you see is a simple melodrama even your

senile granny would have no difficulties in following? Yet without

taking into account ... /the difference between symptom and

sinthom; the structure of the Borromean knot; the fact that Woman

is one of the Names-of-the-Father; etc., etc./ you've totally missed

the point!'

If there is an author whose name epitomizes this interpretive

pleasure of 'estranging' the most banal content, it is Alfred Hitch

cock. Hitchcock as the theoretical phenomenon that we have

witnessed in recent decades - the endless flow of books, articles,

university courses, conference panels — is a 'postmodern' pheno

menon par excellence. It relies on the extraordinary transference his

work sets in motion: for true Hitchcock aficionados, everything has

meaning in his films, the seemingly simplest plot conceals un

expected philosophical delicacies (and - useless to deny it - this

book partakes unrestrainedly in such madness). Yet is Hitchcock,

for all that, a 'postmodernist' avant la lettre? How should one locate

him with reference to the triad realism—modernism—postmodernism

elaborated by Fredric Jameson with a special view to the history of

cinema, where 'realism' stands for the classic Hollywood — that is,

the narrative code established in the 1930s and 1940s, 'modernism'

for the great auteurs of the 1950s and 1960s, and 'postmodernism' for

the mess we are in today - that is, for the obsession with the

traumatic Thing which reduces every narrative grid to a particular

failed attempt to 'gentrify' the Thing?1

For a dialectical approach, Hitchcock is of special interest

precisely in so far as he dwells on the borders of this classificatory

triad2 - any attempt at classification brings us sooner or later to a

paradoxical result according to which Hitchcock is in a way all three

of them at the same time: 'realist' (from the old Leftist critics and his

torians in whose eyes his name epitomizes the Hollywood ideo

logical narrative closure, up to Raymond Bellour, for whom his

2

Description:Hitchcock is placed on the analyst's couch in this volume of case-studies, as its contributors sweep on the entire Hitchcock oeuvre, from "Rear Window" to "Psycho" as an exemplar of "postmortem" defamiliarization. Starting from the premise that "everything has meaning" the films' ostensible narrativ