Table Of ContentC H E N E Y

The Untold Story of America’s

Most Powerful and Controversial

Vice President

S t e p h e n F . H a y e s

To Carrie

thanks for your help.

sfh

CONTENTS

Author’s Note v

Introduction 1

1. The West 11

2. To Yale and Back 27

3. Choosing Government 49

4. The Ford Years 70

5. On the Ballot 122

6. Leadership 159

7. At War 204

8. President Cheney? 253

9. Another George Bush 273

10. The Bush Administration 302

Photographic Insert

11. September 11, 2001 326

12. Secure, Undisclosed 348

vi Contents

13. Back to Baghdad 368

14. The War over the War 394

15. War and Politics, Politics and War 423

16. Dick Cheney: New Democrat? 466

17. “The Alternative Is Not Peace” 494

Notes 525

Acknowledgments 559

Index 563

About the Author

Credits

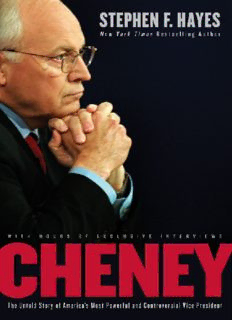

Cover

Copyright

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

O

n June 23, 2004, I waited in the foyer of the vice presi-

dent’s residence for my first one-on-one interview with

Dick Cheney. Writing a book like this had crossed my mind, but

I was at work on another project and busy with my duties at the

Weekly Standard.

There was much to discuss. My first book, The Connection,

had been released earlier in the month, and among top Bush ad-

ministration officials, Cheney was one of the most receptive to

the argument that Iraq had been part of a broad global terror

network that included Al Qaeda. Leaks about the forthcom-

ing 9/11 Commission Report suggested that it would downplay

those ties. The Senate Select Intelligence Committee would soon

release its own report on the intelligence about Iraq that guided

policymakers before the war.

There was a lot of other news. In the morning papers were

several stories about the Bush administration’s detainee policy.

Earlier that same month, CIA Director George Tenet had re-

signed, and congressional Democrats were pushing the White

House to defer the selection of a successor until after the election

in November.

I was to have thirty minutes, on the record. Shortly before

we were to begin, Cheney’s communications director, Kevin

vi Author’s Note

Kellems, approached me with bad news. Scooter Libby, the vice

president’s chief of staff, had just changed the ground rules: No

questions about Iraq and terrorism.

That’s unacceptable, I protested, or words to that effect. He

was sympathetic. If my questioning is restricted in that manner,

I explained, then I’d write about the apparent unwillingness of

Cheney to talk about the issue that was being discussed every-

where else. He took my complaint back to Libby and returned

with good news.

“It’s all on the record,” he said. “Ask what you want.”

We sat in the library. Kellems and Libby stayed in the room.

For forty-five minutes, Cheney sipped a decaf latte as he an-

swered questions or, in several cases, didn’t.

There had been little actual news about the selection of a new

CIA director, so advancing the story would require only a short

comment from Cheney. Make the vice president talk about the

ideal candidate, I naively thought, and perhaps he’d say some-

thing revealing.

In the search for a new CIA director, can you briefly describe

what kinds of qualities you are looking for or what kind of per-

sonal characteristics you are looking for?

“Probably not.”

I waited for him to continue, but he said nothing.

Is there a rough timeline for a decision?

“If there were, I wouldn’t want to talk about it.”

At another point, I asked him about new reports on prewar

intelligence.

Russian president Vladimir Putin said recently that before the

Iraq War began he gave the Bush administration information

about potential Iraqi attacks on American soil. What kind of in-

formation was it and how serious was it?

“Yeah, I can’t really give you anything on that.”

Abu Musab al Zarqawi is the most dangerous man in Iraq.

Can you talk about U.S. efforts to capture or kill him?

“There’s nothing I can give you on that.”

Not all of Cheney’s answers were so brief, but he clearly knew

where he wanted to draw a line. There were subjects he would

discuss and others he would not.

Author’s Note vii

Over the next thirty-four months, I would spend nearly thirty

hours in one-on-one interviews with Cheney for this book: on

the telephone from my home; on my cell phone from a dingy

Wyoming motel; at the vice president’s residence in Washington,

D.C.; aboard Air Force Two somewhere over the Midwest, and

again flying back from Afghanistan, and another time returning

from Iraq.

He was considerably more forthcoming. Cheney spoke about

his boyhood in Nebraska, his difficulties at Yale, and his two

arrests for drunk driving. He talked about the psychological im-

pact of having a heart attack at thirty-seven, the power struggles

of the Ford administration, his frustrations in Congress, the high

points and low points of his time at the Pentagon, and the cross-

country driving trip he took alone as he considered a run for

the White House. We discussed the dynamics of the Bush ad-

ministration, his role as vice president, his reaction to 9/11. He

surprised me with his candor about the mistakes of postwar Iraq

and the personal and professional toll of the unrelenting criticism

directed his way.

But he still knew where he wanted to draw a line. On Au-

gust 9, 2006, I interviewed him at his home in Jackson, Wyoming,

as I had the previous summer and would again in two weeks.

Cheney was relaxed and actually seemed to be enjoying the in-

terview. Throughout our conversation, now in its fifth hour, he

had been remarkably open about his career in Congress and as

secretary of defense.

There had been exceptions, though, as there had been two

years earlier. To set up an amusing anecdote, he told me about an

urgent call summoning him to the White House on his first day

at the Pentagon. When he finished the story, I asked what seemed

like an obvious follow-up.

Do you remember what the meeting at the White House was

about?

Pause.

“I do.”

There was a long silence. I looked at him expectantly, raised

my eyebrows and gave him an encouraging, out-with-it nod of

my head. He laughed a little, but said nothing.

viii Author’s Note

“Umm,” I said, “anything you can talk about?”

“It’s classified still.”

I told this story to another journalist traveling with me on

one of Cheney’s trips, a highly respected White House corre-

spondent for one of the country’s leading newspapers. We chat-

ted a bit about covering the Bush White House and about writing

books. Then he asked me a question that has stuck in my mind

ever since.

“Don’t you think your book will have to be a hatchet job in

order to have any credibility?”

From his perspective it must have been a reasonable concern.

After all, I write for the Weekly Standard, a conservative

magazine that has often supported the Bush administration, par-

ticularly in foreign and national security policy matters where

Cheney’s influence is greatest. One of my articles ran under the

headline: “Dick Cheney Was Right.” It was a lengthy defense of

Cheney, pushing back against misreporting of his views by the

mainstream press. The article offered lots of supporting docu-

mentation, and a heavy dose of outrage.

This book, a reported biography, has a different and much

simpler purpose: to tell the story of Dick Cheney’s life. And

while I came to the book sympathetic to Cheney’s views, I tried

to go where the reporting took me. It will be up to others to de-

termine whether I succeeded or failed.

At several points in the book, I describe a different Dick

Cheney from the one who has emerged from more than six years

of scrutiny in the White House. Given the access I had to him

and those closest to him, that is not surprising. In an e-mail to

a top Cheney aide, Bill Keller, executive editor of the New York

Times, tried to persuade Cheney to cooperate more with report-

ers from his paper. Keller said that understanding political fig-

ures, particularly conservatives, requires access and journalists

who possess “a deep quality of open-mindedness” and “an abil-

ity to listen without reflexive cynicism.” He continued: “Our job

is not to ‘support’ our leaders, not to buy in to any administra-

tion, Democrat or Republican, but our job should be to figure

out what they believe and why, and how all of that shapes the

Description:During a forty-year career in politics, Vice President Dick Cheney has been involved in some of the most consequential decisions in recent American history. He was one of a few select advisers in the room when President Gerald Ford decided to declare an end to the Vietnam War. Nearly thirty years la