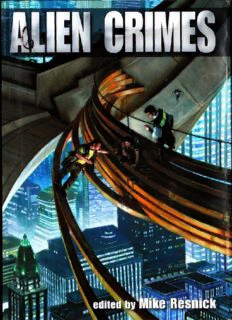

Table Of ContentMike Resnick (ed) – Alien Crimes

ALIEN CRIMES

Edited by

Mike Resnick

SCIENCE FICTION BOOK CLUB

Compilation and Introduction copyright © 2007 by Mike Resnick

“Nothing Personal” copyright © 2007 by Pat Cadigan “A Locked-

Planet Mystery” copyright © 2007 by Mike Resnick “Hoxbomb”

copyright © 2007 by Harry Turtledove “The End of the World”

copyright © 2007 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“Dark Heaven” copyright © 2007 by Gregory Benford “Womb of

Every World” copyright © 2007 by Walter Jon Williams

All rights reserved.

First Science Fiction Book Club printing April 2007

Published by Science Fiction Book Club, 401 Franklin Avenue,

Garden City, New York 11530. Visit the SF Book Club online at

www.sfbc.com

Book design by Christos Peterson

ISBN: 978-1-58288-223-9

Printed in the United States of America an ebookman scan

Contents

Mike Resnick (ed) – Alien Crimes

Contents

INTRODUCTION

NOTHING PERSONAL by Pat Cadigan

A LOCKED-PLANET MYSTERY by Mike Resnick

HOXBOMB by Harry Turtledove

THE END OF THE WORLD by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

DARK HEAVEN by Gregory Benford

WOMB OF EVERY WORLD by Walter Jon Williams

End of Mike Resnick (ed) - Alien Crimes

INTRODUCTION

TWO YEARS ago I edited Down These Dark Spaceways, an

anthology of six hard-boiled science fiction detective novellas,

for the Science Fiction Book Club. It was pretty well received:

Robert J. Sawyer’s novella was nominated for a Hugo and a

Nebula, Catherine Asaro’s was nominated for a couple of

awards, others appeared in various Best-of-the-Year

anthologies.

So last year I approached the book club and suggested we do

another. They agreed, with the stipulation that this book of alien

crimes not contain any hard-boiled mysteries, that we show that

the infinitely adaptable field of science fiction is able to

encompass all kinds of mysteries. After all, Alfred Bester’s The

Demolished Man and Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel, the two

archetypal science fictional mysteries, weren’t hard-boiled

novels.

Hence, Alien Crimes. Once again I chose some of the very

best writers in the field and put the challenge to them: give me

a science fiction mystery, make it novella length, play fair with

the reader, and this time let’s have no genuflecting to the

Hammett/Chandler school of writing. In due time they delivered

their stories, and I think you’ll find the broad range of

approaches and subject matter as interesting as the mysteries

themselves. Hugo winner and best seller Harry Turtledove

examines the odor of crime in Hoxbomb; I bring back my Down

These Dark Spaceways detective Jake Masters, but this time

he’s working for the police and trying to solve A Locked-Planet

Mystery; Hugo winner and Edgar nominee Kristine Kathryn

Rusch demonstrates that things are not always what they seem

in End of the World; Hugo nominee and Clarke winner Pat

Cadigan gives us an interesting lady investigator with a unique

problem to solve in Nothing Personal; Nebula winner Gregory

Benford seems to be telling a contemporary mystery in Dark

Heaven, and then proves that appearances can be deceiving;

and finally, in Womb of Every World, Nebula winner Walter Jon

Williams brings you a story that... well, whatever you think it is,

it’s almost certainly not.

I think, like its predecessor, this book proves that science

fiction can always bring something fresh and new to other forms

of fiction—especially the mystery story.

—Mike Resnick

NOTHING PERSONAL by Pat Cadigan

Detective Ruby Tsung could not say when the Dread had first

come over her. It had been a gradual development, taking place

over a period of weeks, possibly months, with all the subtlety of

any of the more mundane life processes—weight gain, graying

hair, aging itself. Time marched on and one day you woke up to

find you were a somewhat dumpy, graying, middle-aged

homicide detective with twenty-five years on the job and a hefty

lump of bad feeling in the pit of your stomach: the Dread.

It was a familiar-enough feeling, the Dread. Ruby had known

it well in the past. Waiting for the verdict in an officer-involved

shooting; looking up from her backlog of paperwork to find a

stone-faced Internal Affairs Division officer standing over her;

the doctor clearing his throat and telling her to sit down before

giving her the results of the mammogram; answering an

unknown trouble call and discovering it was a cop’s address.

Then there were the ever-popular rumors, rumors, rumors: of

budget cuts, of forced retirement for everyone with more than

fifteen years in, of mandatory transfers, demotions, promotions,

stings, grand jury subpoenas, not to mention famine, war;

pestilence, disease, and death—business as usual.

After a while she had become inured to a lot of it. You had to

or you’d make yourself sick, give yourself an ulcer, or go crazy.

As she had grown more experienced, she had learned what to

worry about and what she could consign to denial even just

temporarily. Otherwise, she would have spent all day with the

Dread eating away at her insides and all night with it sitting on

her chest crushing the breath out of her.

The last ten years of her twenty-five had been in Homicide

and in that time, she had had little reason to feel Dread. There

was no point. This was Homicide—something bad was going to

happen so there was no reason to dread it. Someone was going

to turn up dead today, tomorrow it would be someone else, the

next day still someone else, and so forth. Nothing personal, just

homicide.

Nothing personal. She had been coping with the job on this

basis for a long time now and it worked just fine. Whatever each

murder might have been about, she could be absolutely certain

that it wasn’t about her. Whatever had gone so seriously wrong

as to result in loss of life, it was not meant to serve as an omen,

a warning, or any other kind of signifier in her life. Just the facts,

ma’am or sir. Then punch out and go home.

Nothing personal. She was perfectly clear on that. It didn’t

help. She still felt as if she had swallowed something roughly

the size and density of a hockey puck.

There was no specific reason that she could think of. She

wasn’t under investigation—not as far as she knew, anyway,

and she made a point of not dreading what she didn’t know. She

hadn’t done anything (lately) that would have called for any

serious disciplinary action; there were no questionable medical

tests to worry about, no threats of any kind. Her son, Jake, and

his wife, Lita, were nested comfortably in the suburbs outside

Boston, making an indecent amount of money in computer

software and raising her grandkids in a big old Victorian house

that looked like something out of a storybook. The kids e-mailed

her regularly, mostly jokes and scans of their crayon drawings.

Whether they were all really as happy as they appeared to be

was another matter but she was fairly certain they weren’t

suffering. But even if she had been inclined to worry unduly

about them, it wouldn’t have felt like the Dread.

Almost as puzzling to her as when the Dread had first taken

up residence was how she had managed not to notice it coming

on. Eventually she understood that she hadn’t—she had simply

pushed it to the back of her mind and then, being continuously

busy, had kept on pushing it all the way into the 'Worry About

Later file, where it had finally grown too intense to ignore.

Which brought her back to the initial question: when the hell

had it started? Had it been there when her partner, Rita Castillo,

had retired? She didn’t remember feeling anything as

unpleasant as the Dread when Rita had made the

announcement or later on, at her leaving party. Held in a cop

bar, the festivities had gone on till two in the morning and the

only unusual thing about it for Ruby had been that she had gone

home relatively sober. Not by design and not for any specific

reason. Not even on purpose—she had had a couple of drinks

that had given her a nice mellow buzz, after which she had

switched to diet cola. Some kind of new stuff—someone had

given her a taste and she’d liked it. Who? Right, Tommy

DiCenzo; Tommy had fifteen years of sobriety, which was some

kind of precinct record.

But the Dread hadn’t started that night; it had already been

with her then. Not the current full-blown knot of Dread, but in

retrospect she knew that she had felt something and simply

refused to think about the bit of disquiet that had sunk its

barbed hook into a soft place.

But she hadn’t been so much in denial that she had gotten

drunk. You left yourself open to all sorts of unpleasantness

when you tied one on at a cop’s retirement party: bad thoughts,

bad memories, bad dreams, and real bad mornings-after. Of

course, knowing that hadn’t always stopped her in the past. It

was too easy to let yourself be caught up in the moment, in all

the moments, and suddenly you were completely shitfaced and

wondering how that could have happened. Whereas she

couldn’t remember the last time she’d heard of anyone staying

sober by accident.

Could have been the nine-year-old that had brought the

Dread on. That had been pretty bad even for an old hand like

herself. Rita had been on vacation and she had been working

alone when the boy’s body had turned up in the Dumpster on

the South Side—or South Town, which was what everyone

seemed to be calling it now. The sudden name-change baffled

her; she had joked to Louie Levant at the desk across from hers

about not getting the memo on renaming the ’hoods. Louie had

looked back at her with a mixture of mild surprise and

amusement on his pale features. “South Town was what we

always called it when I was growing up there,” he informed her,

a bit loftily. “Guess the rest of you finally caught on.” Louie was

about twenty years younger than she was, Ruby reminded

herself, which meant that she had two decades more history to

forget; she let the matter drop.

Either way, South Side or South Town, the area wasn’t a

crime hotspot. It wasn’t as upscale as the park-like West Side or

as stolidly middle/working class as the Northland Grid but it

wasn’t East Midtown, either. Murder in South Town was news;

the fact that it was a nine-year-old boy was worse news and

worst of all, it had been a sex crime.

Somehow she had known that it would be a sex crime even

before she had seen the body, lying small, naked, and broken

amid the trash in the bottom of the Dumpster. Just what she

hadn’t wanted to catch—kiddie sex murder. Kiddie sex murder

had something for everyone: nightmares for parents, hysterical

ammunition for religious fanatics, and lurid headlines for all.

And a very special kind of hell for the family of the victim, who

would be forever overshadowed by the circumstances of his

death.

During his short life, the boy had been an average student

with a talent for things mechanical—he had liked to build

engines for model trains and cars. He had told his parents he

thought he’d like to be a pilot when he grew up. Had he died in

some kind of accident, a car wreck, a fall, or something equally

unremarkable, he would have been remembered as the little

boy who never got a chance to fly—tragic, what a shame, light a

candle. Instead, he would now and forever be defined by the

sensational nature of his death. The public memory would link

him not with little-kid stuff like model trains and cars but with

the pervert who had killed him.

She hadn’t known anything about him, none of those specific

details about models and flying when she had first stood gazing

down at him; at that point, she hadn’t even known his name.

But she had known the rest of it as she had climbed into the

Dumpster, trying not to gag from the stench of garbage and

worse and hoping that the plastic overalls and booties she had

on didn’t tear.

That had been a bad day. Bad enough that it could have

been the day the Dread had taken up residence in her gut.