Table Of ContentSECOND

EDITION

AMELIA KLEM OSTERUD

TAYLOR TRADE PUBLISHING

Lanham • Boulder • New York • London

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 1 7/30/14 1:16 PM

Published by Taylor Trade Publishing

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Text © 2009 by Amelia Klem Osterud

Images © 2009 by Amelia Klem Osterud, unless otherwise noted

First Taylor Trade edition 2014

Illustration and design by Margaret McCullough

Back cover photograph: Ringling Brothers, courtesy of Circus World Museum

Author photograph: Courtesy of Lois Bielefeld

Contents page photograph: Tattooed lady Miss Lulu, courtesy of Ronald G. Becker

Collection, Syracuse University Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic

or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written

permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

The first edition of this book was previously cataloged by the Library of Congress as follows:

Osterud, Amelia Klem.

The tattooed lady : a history / by Amelia Klem Osterud

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Tattooing—Social aspects—United States. 2. Tattooed people—United States—Social

conditions. 3. Working class women—United States—Social conditions. 4. Sideshows—

United States. I. Title.

GT2346.U6O87 2009

391.6'5—dc22

2009014350

ISBN: 978-1-58979-996-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-1-58979-997-4 (electronic)

™

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American

National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library

Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 2 7/30/14 1:16 PM

T D o

o ann

a

cknowleDgmenTs

Special thanks to Erin Foley and Peter Shrake at Circus World in

Baraboo, whose vast knowledge of their collections made this book

possible. Thanks to Ward Hall, Charlene Pickle, Tom Palazzolo,

and the late Charlie Roark and Lorrett Fulkerson for sharing your

memories with me, and also to Thrill Kill Jill, Charon Henning, and

the late Sparkly Devil for taking the time to tell me about your careers.

Thanks to Merry Wiesner-Hanks for all your encouragement and

feedback, and also Genevieve McBride and Michael Gordon.

Thanks also to Sam Tracy, Max Yela, Holly Wilson, Brittany Larson,

Mark Jaeger, Luc Sante, Maureen Brunsdale, James Taylor,

Derek Lawrence, Susan Hill Newton, Jane DeBroux, Lelan McLemore,

Alice Snape, and Zsa Zsa Matteson. And of course, thank you to

my husband, DannO, for being my in-house editor, sounding board,

backup memory, and constant voice of encouragement.

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 3 7/30/14 1:16 PM

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 4 7/30/14 1:16 PM

InTroDu cTIon...1

T P

heIr lace In

T h ...

aTToo IsTory 5

T T l ...

he aTTooeD aDy 33

T D c

he ay The Ircus

c T ...

ame To own 69

c c ...

hoIces anD onTrol 99

T l ...

he egacy 125

s ...

ources 136

a a ...

bouT The uThor 149

I ...

nDex 150

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 5 7/30/14 1:16 PM

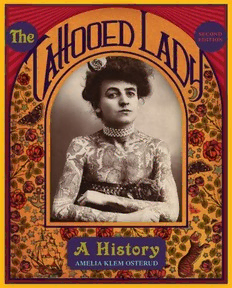

Early tattooed lady Emma de Burgh in a scandalously

revealing outfit, 1880s. Used with permission from Illinois

State University’s Special Collections, Milner Library

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 6 7/30/14 1:16 PM

Tattoos have been a lifelong fascination for

me; I grew up drawing on my body with

colored markers to create my own tattoos be-

fore getting my first real one at age eighteen.

My tattoos are a major part of my identity;

I am proud of the stories they tell about my

life. However, I didn’t know much about the

greater history of tattooing until a chance

discovery in graduate school, where I was

studying history and library science. I was

taking a class on Native American women’s

history and learned that many Native women

(and men) were tattooed or marked in some

manner. Even though I was more interested

in studying women’s labor history, I delved

into the subject of Native American women’s

tattooing and found that nineteenth-century

documents held a wealth of information about

Betty Broadbent in one of her stage tattooing.

costumes, 1920s. Courtesy of Circus I went deeper, looking for books about

World Museum, Baraboo, Wisconsin the history of Western women and tattooing,

and found, to both my horror and delight, al-

most nothing. Women are mentioned in general tattooing history only

in passing or as an aside. Sometimes, they just show up in books of his-

torical images of tattooing, mixed in with men with bad prison tattoos,

completely out of context. However, there were a few women who kept

popping up ever so briefly in my research; these were the tattooed ladies,

a group of interesting sideshow performers with unbelievable tales. Betty

Broadbent, La Belle Irene, Annie Howard. Their names were mentioned,

but little else. Tattooed ladies were a part of forgotten American history,

often dismissed in print as second-rate circus freaks or as monstrous, yet

sexy, anomalies. These women were left to languish in a past that didn’t

know what to do with them when they were alive, and a present that

wasn’t sure what to do with their memory—that is, until now. I’m here to

tell their stories and to celebrate their contributions to American history.

When asked in a 1934 interview why she got tattooed, Artoria the

Tattooed Girl admitted, “I got tattooed because I wanted to get tattooed;

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 1 7/30/14 1:16 PM

it’s a nice way to make a living. You

wouldn’t believe, though, how many

people come up an’ ask if I was born this

way.” Anna Mae Gibbons, who performed

as Artoria for more than fifty years with

various circus sideshows, dime museums,

and carnivals, always affirmatively an-

swered that question onstage: “The doctors

figure it was on account of my mother

must have gone to too many movies.”

Tattooed ladies graced sideshow

and carnival stages until 1995, when the

last performing tattooed lady, Lorett

2 Fulkerson, retired from the carnival

circuit at age eighty. For just over one

hundred years, women who were not

afraid of being different took advantage

Artoria Gibbons, tattooed lady, 1920s. of the weird perceptions that Americans

had about tattooing. The medieval idea

of “impression,” a mark left on a baby in the womb because of some-

thing the mother witnessed, which Artoria referred to in the afore-

mentioned 1934 interview, was clearly alive and well in the minds of

American circus audiences well into the twentieth century. Other ideas

about tattoos and those who had them were just as strange. Hospitals

quarantined patients with tattoos, regardless of the condition or age of

the tattoo, due to fear of disease and infection. Cities banned tattoo-

ing because they thought it spread cancer. To some, tattoos were the

mark of a “savage” or a sign of a criminal mind, and on a woman, it

clearly meant she was a prostitute. “Scientific” minds studied tattoos on

individuals and deemed these people unfit for civilization. Yet, despite,

or perhaps because of, the supposed danger, tattoos were considered

exotic and sexy—the gutsy tattooed women onstage wore short skirts

and skimpy tops to show off their body art. Then, like today, sex and

danger sold tickets.

These tattooed performers came of age when it was unseemly

for women to show their ankles in public, much less display their tattoo-

covered arms, legs, and chests for paying audiences. That they chose this

type of career is both remarkable and courageous, especially since many

came from impoverished backgrounds. Despite the myth of the American

dream, working-class women were born poor and stayed poor because

they had little education or options. Going to school, working their way

up the ladder—these were not alternatives available to them, and because

of these limitations they lacked the ability to make choices that would

help them break out of their class. The decision to get tattooed and go

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 2 7/30/14 1:16 PM

on the road allowed women to achieve things that few others, especially

working-class women, could even imagine.

Their histories, both real and faked for the sideshow audience, show

us exactly how important these women were to developing American cul-

ture. Their sideshow stories are, without a doubt, reflections of America’s

nightmares and dreams. Early tattooed lady Nora Hildebrandt’s story is

one of capture by “savage Indians” and torture by tattoo at the hands of

her father. Artoria’s famous story involves her running off as a teenager

to join the sideshow and become a tattooed muse. When you pair these

fabrications with what has been uncovered about their actual lives, the

differences are both telling and fascinating.

Their real biographies are obscure and have been pieced together

from work histories, photographs, newspaper articles, advertisements,

genealogical documents, and interviews. Putting tattooed ladies in their 3

proper context requires knowing where they fit in circus and sideshow

history, the history of tattooing, as well as nineteenth- and early-twen-

tieth-century women’s history. These were not women who left memoirs,

diaries, or letters. These were hardworking women who spent a majority

of their careers traveling, living life, getting by.

Ultimately, this book is about how a group of gutsy women found

a better way, for them, to survive and flourish, and how their decisions

impact us today.

Ringling Brothers sideshow bannerline and big top entrance,

1898. Courtesy of Circus World Museum, Baraboo, Wisconsin

14_312_TattooedLady.indd 3 7/30/14 1:16 PM