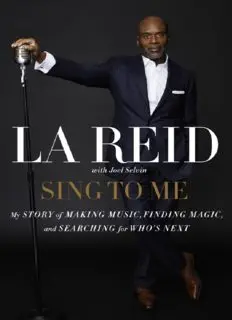

Table Of ContentCourtesy of Ditte Isager/Edge Reps

DEDICATION

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE

LOVING MEMORY OF MY DEAR MOTHER,

EMMA B. REID.

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

PROLOGUE

The Audition

1 Give the Drummer Some

2 Pure Essence

3 The Real Deele

4 The Solar System

5 Girlfriend

6 The Dirty South

7 End of the Road

8 Another Sad Love Song

9 Player’s Ball

10 Waterfalls

11 Nobody Knows It but Me

12 Aristacat

13 Kast Out

14 Culture Clash

15 Emancipation of Me

16 Kingdom Come

17 My Beautiful Dark Twisted Reality

18 X-It

19 Here Comes the Judge

20 Epic Life

EPILOGUE

Showdown at Coachella

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PHOTO SECTION

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

THE AUDITION

I

’d never auditioned a child before. My partner Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds

and I had written and produced records with a couple of boy groups, but working

with kids wasn’t something I’d envisioned doing when we started our own

record company. I vaguely figured I would listen to a song or two and tell the

kid to come back in a few years, but the minute this fourteen-year-old boy

walked into my office that afternoon in 1993, I could tell that there was nothing

that felt remotely childlike about Usher Raymond IV.

These were high times at LaFace Records, the label I had started with

Babyface in Atlanta four years earlier. The company was beginning to make a

name for itself. We had an album about to be released by an unknown singer

named Toni Braxton that would become a multiplatinum smash. The label had

its first multimillion-seller, the soundtrack to the Eddie Murphy movie

Boomerang, and we had sold millions of records with another previously

unknown group called TLC. Babyface had become a star in his own right after

releasing two stellar solo albums and writing dozens of big hit songs with me as

his regular producing partner.

On the heels of all this, we had recently relocated the LaFace office from

Norcross to a bright, beautiful space we’d built out on the fifteenth floor of the

Capital City Plaza building in Buckhead. We built the conference room in the

ten-thousand-square-foot office to be shaped like a piano, which made a curved

wall in the lobby. Nobody ever mentioned that particular design feature, so we

probably spent a lot of money for something that went largely unnoticed. The

staff was growing, as our operation expanded behind our two multimillion-

sellers. The sleek, modern office lent the label an air of prosperity that I hoped

would define us in the years to come.

But with all the success had come some serious adversity. Our top-selling

group, TLC, was unhappy about money, and that was causing problems between

me and my wife, Pebbles, who also happened to be the manager of the group.

And, after scaling the heights of the music business together, from late nights at

chitlin’ circuit dives in the Midwest to the top of the charts, my partner Babyface

and I were inexplicably drifting apart.

What made the growing distance between me and Kenny even more difficult

was that when LaFace started, it was a small operation, just a handful of close

friends who moved out from Los Angeles together. In the early days, LaFace

was a family affair—me, Kenny, our office manager, Sharliss, my wife, Pebbles,

Kenny’s brother-in-law Derek Ladd, Kenny’s childhood friend Daryl Simmons,

my childhood friend Kayo. My younger brother, Bryant, moved from Cincinnati,

where we grew up, to Atlanta and came to work for us. Bryant and I always had

similar tastes in clothes and style—we shared music a lot when we were growing

up. His world revolved around music, fashion, and sports. He was funny and

charming and knew what he was about. Once we signed Toni Braxton, we

assigned her to him, and he became the keeper of all things Toni.

Bryant also scouted talent, and it was through him that I first heard the name

Usher. My brother brought several writers and producers to the label. He caught

Usher at a local talent show—he’d gone to check out another act on the program

—and called me from the show to tell me about him. I wasn’t especially

enthusiastic, but Bryant insisted that the kid was something I needed to see.

Though I hadn’t been running a label for long, finding talent had become a

specialty of mine. Our hit records so far had come from artists who had never

made a record before I auditioned them. You never know what to look for at an

audition; everyone is different, special in their own ways. You have to remain

receptive, open, but without losing your critical and analytical side. It is a tricky

combination of balancing intelligence and intuition and being able to tell the

difference between having a vision and a hallucination.

I auditioned talent in my office three or four times a week, part of my regular

workday. There was a corridor that led to the side-by-side twin offices occupied

by Kenny and me. My office was a big, fluffy, all-white space with furniture

from Kreiss and huge speakers powered by my McIntosh amplifier. Posters of

our artists hung on the walls. People would come in and out to ask questions, to

show me artwork, to get a moment of my attention. I always had an open-door

policy and people knew they could walk in anytime.

It was around two in the afternoon, and I had been listening to some new

songs by Toni Braxton, when this fourteen-year-old kid dressed in blue came to

my office with his mother, Jonetta, and my brother, Bryant. His appearance

looked a little small-town, but his surprising swagger was all big-city. Usher had

grown up in Chattanooga and learned he could sing at an early age. Thinking a

bigger city would be a better place for him to be discovered, his mother had

moved the family to Atlanta, where she worked as a medical technician. She

acted as his manager. He had never auditioned for a record label before.

My routine at auditions rarely varied and was much the same that day. After

a quick introduction and handshake with Usher and his mother, I sat back down

and asked, “What are you going to sing for us?”

I always know in a few seconds. There are very few people who can pass an

audition. I usually know when they walk in the room before they open their

mouth—even if they open their mouth only to speak and not sing. I’ve already

made up my mind. The last few minutes is just me being kind to them. I’ve been

told I’m rude in auditions, but I’m not. I might not look up from my computer,

but I pay attention. I never tell anybody what I think, unless I’m blown away. I

like the theater of leaving it hanging, so that when you do deliver the news, you

create a life-changing moment.

He handed me a tape of an instrumental track. I put it in the cassette player

and pressed Play. He stood in front of my desk and started to sing a song Kenny

and I wrote that had been a record-breaking number one hit for Boyz II Men on

the Boomerang soundtrack called “End of the Road.” He was killing it. He

didn’t get through sixteen bars before I interrupted him.

“Stop, whoa,” I said. “I need to get some girls. I want everybody to hear

you.”

Our bustling office was filled with employees and interns from local

colleges. We rounded up all the pretty girls. They filled the chairs in my office,

perched on desks, leaned in the doorway. About fifteen people crowded in.

Usher took it from the top.

He zeroed in on Phyllis Parker, who worked for us, probably the most

beautiful woman in the room, and dropped to his knee in front of her, singing,

placing his hand on her thigh and looking dead in her eyes. He was seducing her

with the confidence of someone who had done it before.

This kid wasn’t afraid, he wasn’t intimidated, he wasn’t overwhelmed by the

surroundings or the fact that he was singing for a record company president. He

didn’t have any apprehension at all. He jumped in like a pro. It turned out he had

some stage experience in a group he sang with and had done a Star Search

audition, but he was still raw and green. He came by his self-confidence

naturally.

When he opened his mouth to sing, he didn’t sing it like Boyz II Men, he

sang it like it was his own song. His tone was perfect for the way he sang the

song; he gave it his own, original sound, which is what I always look for with

people—that special voice stamp that is only yours, that will not be mistaken for

anyone else. The voice there was all his own. He was his own person. He was

already Usher.

He was confident and poised way beyond his years. His eyes told the story.

He had eyes of steel. He knew he would be a star. I could see that commitment

in his eyes. He was charming. He could dance his ass off. He had an

unbelievable vocal tone and he was a sponge. He sensed exactly what I was

looking for. I knew all this in an instant.

When he finished, the room exploded in applause and I stood up.

“Welcome to LaFace Records,” I said.