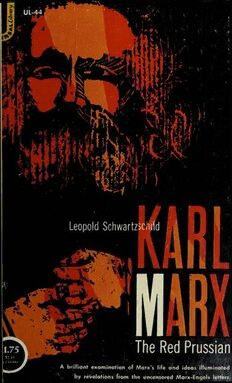

Table Of ContentA brilliant examination of Marx’s life and ideas illuminated

• - * • w* «. % •

by revelations from the uncensored Marx-Engels letters.

Jfylarx

^ I

at

THE RED PRUSSIAN

THE RED PRUSSIAN

LEOPOLD SCHWARZSCHILD

niversarl dj^aY

e

GROSSET 8c DUNLAP

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1947, BY CHARLES SCRIBNER S SONS

Under the title: The Red Prussian, TAe Life and Legend of Karl Marx

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN

ANY FORM WITHOUT THE PERMISSION OF CHARLES SCRIBNER S SONS

Sol

i 4-7

BY ARRANGEMENT WITH CHARLES SCRIBNER S SONS

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY MARGARET WING

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oft utf

To my wife,

whose unerring criticism, stimulating sug

gestions and constant encouragement have

contributed so much to every page of this

book.

15342

PREFACE

had to be found for the age in which we live, we

f a name

I

might safely call it the Marxian era. For, in one way or

another, the most important facts of our time lead back to

one man—Karl Marx. It will hardly be disputed that it is he

who is manifested in the very existence of Soviet Russia, and

particularly in the Soviet methods. Even the orthodox Marxists,

who regard the influence of personalities on the course of history

in general as negligible, and that of “objective forces” as decisive,

make an exception in this case. Without Marx there would have

been no Lenin, without Lenin no communist Russia. But, indi

rectly, Marx is also responsible for all the other totalitarian

states, since all of them, rivals of Soviet Russia though they may

be, are at the same time imitations or variations of the Soviet

model. And after all, it is because of Marx that the rest of the

world has for years been obliged to sacrifice one after another

of its liberal traditions to the necessity for self-preservation. There

can be no doubt that our whole life would be very different if

Marx had never lived.

“The tree is known by his fruit.” Practically all the previous

biographies of Marx were written many years ago, before any

fruit had ripened. The biographers of those days—admirers and

believers—were convinced that this fruit could only prove bene

ficent, and they viewed their subject in the light of this anticipated

blessing. But the picture which is presented to us in the light of the

actual effects of Marx and Marxism has little in common with the

fictions of the old biographers. Features now emerge which had

formerly been overlooked; while others which were pure inven

tion disappear. If the present book gives an interpretation of

Marx which differs vastly from the conventional version, it is

because the fruit which makes known the tree has in the meantime

ripened and assumed tangible form.

And there is another reason why it is possible for this book

vn

PREFACE

to reach beyond the previous biographies. In recent times a body

of material has been made available which was not at the dis

posal of the earlier writers—the complete correspondence of Marx

and Engels. It is true that a collection of these letters was pub

lished shortly before the first World War by the German Socialist

party. But this collection, as it turned out later, was deliberately

and carefully purged of everything which could place Marx in

an unfavorable light. Hundreds of letters were omitted, in count

less others whole sentences and even paragraphs were cut out,

while in hundreds of others compromising expressions were

changed. It is hard to understand what prompted the Marx-

Engels Institute in Moscow to supersede this piously falsified

collection with a complete unvarnished edition. Apparently the

mental and moral schism between Soviet Russia and the rest of

the world had grown so deep that the editors were not even

conscious that they were doing a poor service to the memory of

their hero. However that may be, these letters, which over a

period of forty years passed between the two pioneers of com

munism, in which they voiced their most intimate thoughts and

related their most secret activities—these letters we now have at

our disposal. They reveal to us, instead of the legendary, the

true Marx. There is scarcely any important historical figure about

whose character we have even approximately such exhaustive

and authentic information as we now have—thanks to these four

volumes—about the character of Marx. Amidst the turmoil and

cares of the Thirties this amazing compilation, published in

German, attracted practically no attention, and the four volumes

disappeared without a ripple in the depths of the libraries. It

is a privilege to bring them to light.

It may be added that this book makes no assertion, relates

no episode, and emphasizes no trait in Marx’s character without

clinching the point by means of authentic quotations, and in

forming the reader where these quotations may be verified.

L. S.

New York, February, 1947.

• • •

Vlll

CONTENTS

Preface vii

Chapter Page

I. THE BRAIN OF HIS ANCESTORS I

II. THE FRUSTRATED POET 16

m. THE ALL-POWERFUL “it” 30

IV. DOWN WITH SOCIALISM! 46

V. LONG LIVE SOCIALISM! 69

VI. THE ECONOMIC ABYSS 86

vn. OUR THEORY I I 7

VUI. THE FANFARE 137

IX. THE BANNER OF THE GAULS 163

X. THE FALSE FLAG l8o

XI. WHERE IS YOUR PROOF? 217

XII. TWO CHAPTERS 234

xm. “baron izzy” 267

XIV. THE THREE LABORS OF HERCULES 289

XV. INTERMEZZO 318

XVI. THE LAST BATTLE 346

XVH. ON THE SHELF 393

REFERENCES 408

INDEX 41 I

1X

THE BRAIN OF HIS ANCESTORS

H M , the lawyer, was baptized in the

hen erschel arx

W

autumn of 1816,1 the people of Trier were a trifle

shocked. Countless Jews in Western Europe were at

that time making their way from the temple to the church. In

those optimistic days it seemed the best way of getting finally rid

of those prejudices which were, fortunately, already on the wane.

For the most part, people rejoiced at every conversion. This

particular one, however, was not entirely relished either by the

Jews or the Christians in Trier.

After all, Herschel Marx belonged to the family which had

given Trier its rabbis for a hundred and fifty years. At the

moment, his brother held office; before that it had been his

father; before him his grandfather on his mother’s side, and still

further back, his great-grandfather and his great-great-grand-

father. Moreover, long before the forefathers of Herschel Marx

had become the almost hereditary shepherds of the flock in Trier,

they had been rabbis in other cities. For many centuries not one

of his ancestors had practised any other profession. Congregations

in far distant lands had tried to lure them into their midst, and

many of them had been true spiritual princes in Israel. Those

who knew of him spoke with awe and reverence of Josef ben

Gerson Cohen, who had been the rabbi of Cracow towards the

end of the 16th century. And they spoke with even more bated

breath of Meir Katzenellenbogen, who died in 1565 as rabbi of

Padua, and whose fame extended far beyond the confines of his

synagogue. The great university of Padua counted him among

1 Marx-Chronik. Fall 1816.

THE RED PRUSSIAN

the most illustrious minds of his day, and hung his portrait in

the great hall.2

There was another strange thing about this conversion. The

year before his baptism, Herschel Marx had married, but appar

ently he had not been able to see eye to eye with his young

wife on the question of religion. She was Henriette Pressburger

from Nimwegen, in Holland; she, too, was the product of count

less generations of rabbis; and she, like her husband, was not

really devoted to the faith of her fathers. But, on the other hand,

she felt just as little attracted to the religion which she would

have had to espouse in its place, and so she refused to follow her

husband into the Christian church. What, then, was the Marxes’

real position, and how would they bring up their children, the

first of whom was obviously on the way? Somehow the situation

was not as simple as the good people of Trier would have liked

it to be.

But the people of Trier, Jews and Christians alike, did not

consider themselves their brothers’ keepers. They had always

been willing to live and let live, and, in recent times, tolerance

had become the password of the more progressive spirits. Let

well enough alone, was their motto.

Over the little town hung the scent of the grape-vines which

were cultivated for miles up and down the river. The grapes

of the Mosel valley belonged, together with those of the Rhine,

Burgundy^ Bordeaux and Champagne, to the Big Five of the

wine aristocracy. Mosel wines had long been held in the highest

esteem as far afield as the courts of London and Petersburg; re

cently orders had even come in from that new country, America.

Wine was not only the business of the people of Trier; it had also

had its share in forming their character. For rich and poor alike,

wine was both their daily drinking-water and the crowning glory

of their festive hours. Everyone in Trier could distinguish the

kinds of grapes and the vintages with his eyes shut. Lovingly, yet

critically, they drank their golden wines between meals and with

meals, and they insisted that their food should be of the same fine

3 Bernhard Wachstein: Die Abstammung von Karl Marx (In: Fest-

skrift i Anleding af Professor D. Simonson, Kjobnhavn, 1923).

2