Table Of Content‘. . . the life of a man who is a fountain

of energies and enthusiasms, and an

Australian who must be remembered.’

Tom Keneally

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF

GEORGE COLLINGRIDGE

ADRIAN MITCHELL

Wakefield Press

Plein Airs and Graces

Adrian Mitchell has had a long career at the University of Sydney, where he is

now an Honorary Research Associate in the Department of English. Among

many projects, he edited Bards in the Wilderness: Australian Colonial Poetry to

1920 together with Brian Elliott, and with Leonie Kramer edited the Oxford

Anthology of Australian Literature. He is the author of Drawing the Crow, a book

of essays about what it meant to be South Australian in the 50s and 60s, and of

Dampier’s Monkey: The South Seas Voyages of William Dampier.

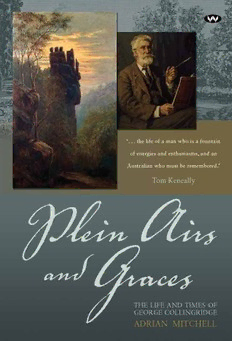

George Collingridge in old age.

Photograph, Collingridge family collection.

Plein Airs and Graces

The life and times of

George Collingridge

Adrian Mitchell

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2012

This edition published 2013

Copyright © Adrian Mitchell, 2012

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for

the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under

the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission.

Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Edited by Penelope Curtin

Cover design by Stacey Zass

Typeset by Wakefield Press

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Mitchell, Adrian, 1941– .

Title: Plein airs and graces [electronic resource]: the life and times

of George Collingridge / Adrian Mitchell.

ISBN: 978 1 74305 213 6 (ebook: pdf).

Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: Collingridge, George, 1847–1931.

Artists – Australia – 19th century – Biography.

Authors, Australian – 19th century – Biography.

French – Australia – Biography.

Dewey Number: 759.994092

Contents

Acknowledgements vi

1 Old Man’s Valley 1

2 Godington 7

3 French Impressions 22

4 The Promised Land 48

5 The Hermitage 62

6 The Woodpecker 74

7 Oil and Water: The landscapes 88

8 Carte Blanche 108

9 Jave la Grande 135

10 The Academy 158

11 Mirror Images 173

Bibliography 195

Notes 203

Index 223

Plates

Acknowledgements

Best to get this out into the open, right up front. This book is my wife’s idea.

She has been badgering me for years to write a book about George Collingridge,

to acknowledge his remarkable life as well as his contribution to the making of

Australian cultural history – a pioneer in every sense other than the familiar one,

in fiction and in fact, of chasing cattle around the outback. George was never one

for running with the conventions. Neither, truth to tell, is my wife.

Now I hope she is satisfied. I would like to think George is satisfied too. This

book is for both of them, but for Maureen especially.

George Collingridge’s name is all but forgotten these days, yet in his time

he was quite a public figure, busy in fostering the art community in Sydney,

promoting progress associations, developing his hypotheses about the early

European discovery of Australia and conducting classes in painting, in French

conversation, in Esperanto and ceaselessly writing thumping letters to the editors

of the newspapers, mainly in Sydney but occasionally in the other colonies too.

He was not easy to overlook then, and he made his mark. But what he stood for

has been steadily overtaken, if not largely set aside. His granddaughters, though,

Winsome and Edith Collingridge, have been valiant in keeping their grandfather’s

story alive. They have been steadfast keepers of the flame. This work benefits

from that perseverance, from their kind hospitality, and from their generosity in

allowing me to view their holdings of his work. I thank them for their permis-

sion to reproduce images and graphic material. So likewise I am grateful for the

enthusiasm of Chris Pond, a great-grandson, who assisted with archival material

and maintained a supportive interest in my progress.

I am indebted to others too who have their own more indirect connection

with the George Collingridge story. Special thanks go to Mrs E.P. List of Neve’s

Croft of Godington in Oxfordshire for her local history and for information

readily provided; to Rev. Father John Burns, Holy Trinity Church, Hethe, also

in Oxfordshire; to Annie Crowe, current owner of Capo di Monte on Berowra

Creek and another enthusiast; to Wendy Escott and Simon Bryan, who provided

the pleasure craft on the day of the excursion there and who also have an

ongoing interest in this history; and to Jill Harvey for sharing her recollections of

Collingridge Point.

I was given ready assistance in matters of local history by Penny Graham; Neil

Chippendale, Local Studies Coordinator at Hornsby Shire Library; Geoff Potter,

Local Studies Librarian, Gosford Public Library; and members of the Hornsby

Historical Association, Elizabeth Roberts and Ralph Hawkins in particular. My

thanks to the Art Gallery of New South Wales for permission to reproduce the

vi

Plein Airs and Graces

J.S. Watkins portrait of George Collingridge, and especially to Tracey Keough

for assistance in arranging this; to the Library Council of New South Wales for

permission to reprint George Collingridge’s facsimile of the Descaliers map of

Jave la Grande held in the Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales,

and in particular to Elise Edmonds and Maggie Patton, Map Librarians at the

State Library of New South Wales, for timely assistance; and to Hornsby Library

for permission to reprint pictures in their possession. I am especially grateful to

Nicholas Keyzer, who photographed the paintings and sketches included here,

battled with domestic crises of various kinds as he worked his magic on them, and

found himself growing more and more taken with the Collingridge project.

My thanks also to the team at Wakefield, especially to Michael Bollen for so

readily accepting the typescript; and to Penelope Curtin for reading it more care-

fully than I had, for catching patches of inconsequential thought and purposeless

expression; and for politely prising my fingers off the semicolon key, though not

always with the success she might have hoped for.

Early in this undertaking I had very productive conversations with John

Spencer, Librarian, Schaeffer Fine Arts Library; Professor Virginia Spate; the

late Dr Noel Rowe; and Professor Ivan Barko, all of the University of Sydney. The

University of Sydney made available a small period of leave to begin the research

for this project.

Some parts of this book are more or less recognisable from earlier appearances,

in papers presented at the Australasian Universities Modern Language Association

conference at the University of New South Wales in February, 2007 (and published

in the proceedings, 2008), and at the conference of the Bibliographical Society of

Australia and New Zealand at the University of Sydney in 2008; and in an article

published in Explorations in December 2008.

vii

1

Old Man’s Valley

At the northern fringe of Sydney, just beyond what is called the Upper North

Shore, and on the high ridge between two large deep creeks that open out into the

Hawkesbury River, is a community known as Hornsby. Now one of the consoli-

dating suburban hubs, for a good many years it managed to preserve something

of the feel, and look, of a country village. George Collingridge, a local landscape

painter, art teacher, woodblock engraver, multilingual historical cartographer,

activist in local matters, editor and author, was one of the early settlers in this part

of the world, one of the first to discover and appreciate the picturesque attractions

of the close-by Hawkesbury River.

Tucked in just below the ridge is a deep valley, Old Man Valley, named it has

been said, for the kangaroos there. The earliest documentation shows the original

lease was for a farm to be known as Old Man’s Valley, the modified name coming

into common use some time later. These days the locals have once more taken to

calling it Old Man’s Valley; that seems somehow more proprietorial, suggesting a

kind of ancestral presence, a connection to the sense of the past, which is still a felt

presence all through the area. Little is disturbed down there. Even the road down

into it seems to have been there a long time, the verges overgrown. The breezes that

whip and toss the thinner branches of the eucalypts on the ridge line and the upper

slopes do not reach down into the valley. Mist hangs about until mid-morning.

Dewdrops map out the dainty webs of spiders. In the late afternoon, the damp

starts to rise again, and mists emerge out of thin air.

At some stage the sun, always slow to rise above the crest, shines through the

drooping leaves and heavy vapour, and just briefly you might catch the whole

underside of the tree canopy scintillating. Right at the bottom of the valley, where

the lyrebirds flicker in and out from under the fern trees, is a creek, a tributary of

Berowra Creek. Native fish gather in shady pools below a waterfall. Small birds –

whistlers, yellow robins, blue wrens – skitter busily about the edges of natural

clearings. The magic of Old Man’s Valley is that it shows itself only in glimpses.

Sunsets are hidden by another high ridge at the far end of the valley; in fact,

much of this country is an ancient plateau eroded into twisting channels that

1

2 Plein Airs and Graces

deepen into gorges. Long shadows are cast hereabouts. At night, when the cloud

cover drifts away, the temperature plummets, and the bluish moonlight is as cold

and sharp as a stiletto. In amongst the tall timber the clumps of foliage look like

ink smudges.

The colours of the forest are mostly cool, although when the sun is directly

above the foliage changes to something close to the familiar yellow-green of

willows, or the monotonous drab olive that the first settlers complained of. That

was of little interest to George Collingridge: at either end of the day or in overcast

weather he found a range of either very dark greens, terre verte, or blue-greens –

the colours familiar from his training in France. A prolific painter, he was not fond

of the high-toned summer skies favoured by the emerging school of Australian

impressionists. At about the time of Federation, or just after, Arthur Streeton’s

elderly father lived on the lip of this valley, and on a visit one Christmas Streeton

painted there, in the middle of the day. Collingridge preferred a cooler register,

though he too had a Christmas epiphany.

In the valley, when it rains, the planes and depths of colouring begin to merge

towards one dark mass; the sombreness of the under-canopy becomes the whole.

Trunks, branches, twigs become more distinctive in the wet, a charcoal tracery, and

then the structure of the trees becomes more visible; but that was not Collingridge’s

interest either. He was not a Hans Heysen, he was more interested in effect. He

had learned directly from Corot, and transposed what he had learned of land-

scape painting in mid-nineteenth-century France to the region around Hornsby,

Berowra, Brisbane Water and the Hawkesbury, again and again defined by and

against water. Water, lakes, rivers, primordial seas fascinated him.

In the 1890s, when George Collingridge de Tourcey took up residence in

Hornsby, there were six houses in the valley. Now there are none. It had been

settled by a clan of Higginses, who started out felling and sawing by hand the

thick stands of blackbutt, blue gum and cedar, and carting off the timbers to the

building sites about Parramatta. In the clearings they planted fruit trees, which

were protected from the brisker weather up on the ridge above, and sustained by

a patch of rich volcanic soil. Theirs was a quiet life, the sides of the valley steep

enough for the Higginses to keep pretty much to themselves on their picturesque

orchards. They had all that they wanted there in the valley, even their own ceme-

tery. Hardy, self-reliant men and women, they established themselves by dint of

their own labour and they were content with their lot. The view down into the

valley from above was a delight. It was a landscape that presented itself to the

artist’s eye. Here, the two values that George Collingridge held most dear – art

and settlement – were on tranquil display. Here, he could find something like those

hints and traces of the Golden Age that had sustained the development of art in

mid-nineteenth-century France, intimations of an idyllic life: in part the manifesta-

tions of a simple and contented existence, and in part, the proximity to that which

had been here from the beginning, ancient, primal.