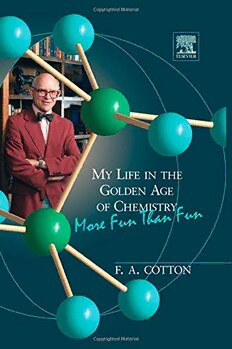

Table Of ContentMy Life in the Golden Age of

Chemistry: More Fun Than Fun

My Life in the

Golden Age of

Chemistry

f. a. cotton!

!Deceased

Amsterdam Boston Heidelberg London New York Oxford

Paris San Diego San Francisco Singapore Sydney Tokyo

Elsevier

Radarweg 29, PO Box 211, 1000 AE Amsterdam, Netherlands

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK

225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA

Copyright © 2014 Jennifer Cotton. Published by Elsevier INC. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage

and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to

seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our

arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright

Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by

the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notice

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and

experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional

practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in

evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described

herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and

the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors,

assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of

products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods,

products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN: 978-0-12-801216-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For information on all Elsevier publications visit our website at http://store.elsevier.com/.

This book has been manufactured using Print On Demand technology. Each copy is

produced to order and is limited to black ink. The online version of this book will show color

figures where appropriate.

Whoever has had the great fortune

To gain a true friend,

Whoever has won a devoted wife,

To the rejoicing let him add his voice.

—Friedrich Schiller

For Dee

F. Albert Cotton M.F.H.

Robert Douglas Hunter

1971

ix

FOREWORD

Immediately after the War, the approach to the study of Inorganic Chemistry

underwent a revolution. This in part arose from the wide range of instrumentation

that became available. The advent of relatively rapid methods for the determination

of infrared, visible and ultraviolet, and Raman spectra coupled with the availability

of new techniques such as n.m.r. and e.s.r. spectroscopy allowed for a wide range of

applications to a variety of problems within Inorganic Chemistry. Many of these had

not been possible or even conceived of before these developments.

This book not only provides an insight into the contributions of one of the major

players in these developments but also encapsulates the atmosphere of the period

when Government funding of science was generous and good research was assured

of sponsorship. This situation has sadly declined worldwide and reflects the very

much bigger scientific community that now exists and the increase in the financial

requirements of modern-day research.

The author is well placed to discuss this position as he entered the field at the

beginning of this period of rapid change. His own initial contribution was in the then

novel field of Organometallic Chemistry, with work on the spectacular new range of

“aromatic” inorganic compounds as typified by ferrocene. His subsequent work over

the next 50 years provided leadership in many of the most significant developing areas

of Inorganic Chemistry, and he has left a heritage that will last for many years.

He certainly excelled in his command of both the theory and practice of his

subject, and his papers and written contributions reflected both his joy and efficiency

in writing. Over a period of approximately 50–60 years, he published over 1600 papers

and a variety of books that covered teaching at all levels—school, undergraduate,

post-graduate, and research monographs. These are all excellent texts and as with, for

instance, in books such as Advanced Inorganic Chemistry and his textbook on group

theory, he provided a new approach and insight to the subjects under discussion. These

books have become classics in their time. His contribution to the chemical literature

x

was outstanding in both quality and quantity, and places him in a unique position

within the chemical community.

This book not only relates to his contribution within research and teaching but

also unfolds the wide appreciation and influence that he made to so many aspects of

life in general. He enjoyed travel and visited many parts of the world, often to relate

his chemistry but also to establish a wide range of contacts and friendships. This in

part reflects the vast range of countries from which his research collaborators came.

As is evident from the text, Al was a strong supporter of his students and built up a

close relationship and concern for their future that often extended for life. He was very

direct in his relationships, and this is evident in his coverage and his reflections on

some of the people that are included in the book. I certainly enjoyed a friendship that

stretched over more than 50 years. I find this book a constant reminder of so many

aspects of Al and his attitudes across a large spectrum of interests. It will provide the

public with an insight into how an outstanding scientist lived, worked, and thought.

It is something of a tragedy that shortly after finishing this book he should meet such

an untimely death. He is missed by many but mostly by his family who were always

paramount in his thinking and behavior. This book reflects the thoughts, attitudes,

and reflections of a remarkable man who made major contributions to his chosen area

of science and has certainly changed the way we view and study the subject.

—The Lord Jack Lewis

Cambridge, England

xi

PROLOGUe

I began this book with considerable trepidation, indeed with the feeling that it might

be wiser not to. Any attempt to recreate the past is bound to be an act of imagination

as well as of recollection. Bias and subjectivity are inescapable. That particular effort

to recreate the past known as autobiography must needs suffer from these distorting

influences in the most extreme degree. In an attempt to mitigate the effects of an

inaccurate memory, I have asked several friends to read the manuscript and point

out errors of fact, and I have benefitted greatly from their perspicacity. naturally,

the responsibility for errors that remain is mine alone. I have discovered the truth of

ernest Hemingway’s observation that for a writer it is necessary to know everything

but to leave out most of it. As for my choice of events and my reconstruction and

interpretation of certain events, they may well be colored by egotism. I have tried to

minimize this, but I have no illusions about the impossibility of avoiding it completely.

Caveat lector! If there are readers who recall certain things that are described here in

a different light, I shall be neither surprised nor necessarily inclined to change my own

view. I would, however, be glad to receive constructive criticism.

Whatever my misgivings about writing my own autobiography for this series, it

was a call I could hardly have refused in view of my role in bringing it into being.

Sometime in the latter part of 1995, after I had read a large number of the Profiles,

Pathways and Dreams series of autobiographies of organic chemists, edited by Jeffrey

I. Seeman and published by the American Chemical Society, I thought that the ACS

might be interested in publishing a similar series of autobiographies of inorganic

chemists. I also discussed the project with Stan kirshner and made the suggestion

that he would be a good editor, but he declined. I then turned to John Fackler and he

carried on from there. He first found that the ACS was not interested (for financial

reasons) and he then persuaded Plenum (now Springer) to be the publisher. Thus,

when John proposed that I write one of the first few volumes in the series, I had to

accept a task I had sort of brought on myself.

xii

Choosing a title for this book was not easy. Had Jack Roberts not preempted In the

Right Place at the Right Time, I might well have used it myself. I believe that in my life

I have benefitted from a lot of good luck and not suffered from any unusual amount

of bad luck. Some of the breaks I have gotten I think I made for myself, and there is,

of course, the very true adage that “the harder I work the luckier I get.” I must admit,

however, that some things, like having both the mother and the wife I have had, were

bounties that I did nothing to deserve. I was the beneficiary of unearned good luck as

well at some other points in my life. Thus, to a significant degree, I have led what is

often called a charmed life. At one point, I considered using that as a title. Other titles

came to mind, but were also rejected. I was growing desperate, when I read in Hans

krebs’ autobiography that noel Coward had, supposedly, said, “Work is fun. There is

no fun like work.” Aha, I said, No Fun Like Work it is, but krebs gave no source for

the quotation and is no longer available to be asked, and I thought it would be nice to

have a more direct attribution. After some searching, I discovered the Reverend James

Simpson’s book Simpson’s Contemporary Quotations, in which Coward is said to have

said “Work is more fun than fun.” Regrettably, Rev. Simpson has no documentation

other than a newspaper obituary. Probably Coward said either one or the other, and

he may even have said both on different occasions. I decided that More Fun than Fun

was to be my subtitle. As to the golden age mentioned in the title, I refer the reader to

my Priestly Medal lecture, reprinted here as an appendix.

Finally, I should like to say to all, friends and foes, that in writing this book I

am in no sense writing an epilogue to my life or even my career. I still get as much

of a thrill as ever from learning something new that no one has ever known before,

even if it’s only a little thing. Seeing a beautiful new molecule for the first time still

exhilarates me as much as it ever did, especially if the molecule has surprising, or better

yet, puzzling features. Thus, while I cannot contest Caesar’s observation that “death,

a necessary end, will come when it will come,” I do not feel in the least receptive to

the idea, and hope to go right on doing chemistry for a long time yet. Moreover, I

strongly believe in Andre Maurois’ dictum that “Growing old is no more than a bad

habit which a busy man has no time to form.”

xiii

TO THe ReAdeR

On October 17, 2006, Al had gone out for his morning walk as he always did on

Tuesday mornings. Al was a creature of habit: on Tuesdays and Thursdays, he would

go on a walk before he went into the office. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday he went

to aerobics with his wife, dee. His route was predictable—with slight variations from

time to time—bringing him home about 8:00 a.m. On this morning, though, things

were different, Al didn’t come back at his normal time.

Al was found at the end of the lane. He had been brutally assaulted.

We had been working on the design and layout of this book for many months and I

had given him what I had hoped would be—though I was sure it would not— the final

proof of the layout the week before. My husband, Carlos Murillo, was in the hospital

on this fateful Tuesday morning, he had had an emergency appendectomy the Friday

before. Al came to the hospital on Sunday to see Carlos and told me that he would

not be back on Monday; he “had to get this book finished, I’m tired of looking at it.”

He told us that he would be back on Tuesday. He was back on Tuesday, but he was

life-flighted into the emergency room in critical condition.

I was able to get the final proof back after the police combed his office for clues and

evidence. In his usual manner, Al left me with just as many questions as answers. He

would indicate that “we have a problem here” referring to an equation, figure, or line

of text, but, since I am not a chemist, I had no idea what the problem was or how to

fix it. That’s just how Al was; he would mark something to remind him to go back and

check on it and forget that he had marked it until I came back and asked him what

the problem was. He put a lot of thought into what was included in his autobiography.

The concept of including things just because they happened was not how he wanted

to approach this. Always the teacher, he wanted what was included to be of use to the

students that would be writing reports on chemists in the future. He was insistent that

some things stay exactly the way that he wrote them. When I asked him if he wanted