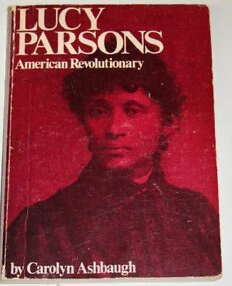

Table Of ContentLUCY

PARSONS

American Revolutionary

by Carolyn Ashbaugh

1976 Chicago

CHARLES H. KERR PUBLISHING COMPANY

Published for the Illinois Labor History Society

~478

©

Copyright 1976

Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company

Printed in the United States of America

LC 75-23909

ISBN 0-88286-005-4 paper

ISBN 0-88286-014-3 cloth

Graphic Design: Pamela Rice and Leo Tanenbaum

Acknowledgments

The Harold A. Fletcher Award from Grinnell College, the

Ralph Korngold Fellowship from the Newberry Library, and a

Youthgrant from the National Endowment for the Humanities

have supported my research. I owe special thanks to Lawrence

W. Towner, Director of The Newberry Library and to Richard

Brown and James Wells, the Associate Directors of the Library,

and to Mrs. Piri Korngold who furnished the Ralph Korngold

Fellowship. My good friend Jane Marcus has encouraged and

assisted my work on Lucy Parsons since its beginning, when I

was a student and she a teacher at the Associated Colleges of

the Midwest and Newberry Library Seminar in the Humanities

the fall of 1972.

Special thanks to my friends Leslie Orear, President of the

Illinois Labor History Society, who first suggested I write a

book about Lucy Parsons, and to Professor William Adelman

of the University of Illinois Institute of Labor and Industrial

Relations and author of Touring Pullman and Haymarket

Revisited, who has shared his extensive research and the excite

ment of each new discovery about Lucy Parsons with me.

Joseph Giganti, Fred Thompson, and Irving Abrams, board

members of the Charles H. Kerr Pub. Co. have shared their

recollections of Lucy Parsons with me. Joe and Fred have offered

valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript. Irwin St.

John Tucker recounted the 1915 Hunger Demonstration for me.

Stella Nowicki, Eugene Jasinski, Mario Manzardo, Francis

Heisler, Henry Rosemont, Clarence Stoecker, Vera Buch

W eisbord, Albert W eisbord, Sid Harris, George Winthers, Abe

Feinglass, Sam Dolgoff, Lucy Haessler, Arthur Weinberg, and

the late James P. Cannon have all shared their knowledge of

Lucy Parsons with me and enriched my knowledge of the history

of the labor and radical movements. The late Boris Yelensky

shared his impressions through lengthy correspondence.

A special thanks to Mrs. Lucie C. Price of Austin, Texas,

who researched the Texas careers of William and .Albert Parsons

4

at the Archives of the University of Texas and the State

Historical Library of Texas.

I owe a debt of appreciation to William D. Parsons and to

Katharine Parsons Russell for discussing with me the effect of

the Haymarket Affair on the Parsons family and to William

Parsons for the picture of his great-grandfather, General William

Henry Parsons.

My friends Sandra Bartky, Laura X, Sara Heslep, Anne

Walter, Mrs. Mae Coy Ball, Tom DuBois, Marcus Cohen and

many others have inspired and encouraged me. Thanks to the

members of the history department at Grinnell College-Don

Smith, Alan Jones, Joseph Wall, David Jordan, Philip Kintner

and Greg Guroff-who have offered suggestions and stimulated

my work and to Florence Chanock Cohen for her critical

comments and editorial suggestions on my manuscript.

Thanks to Hartmut Keil and Theodore Waldinger for

translations from the German. Thanks to Barbara Morgan and

Martin Ptacek for photography. Thanks to Jamie Fogle for art

work and to Sara Heslep for proofreading.

Dione Miles of the Wayne State Labor Archives; Dorothy

Swanson of the Tamiment Institute, New York University;

Edward Weber of the Labadie Collection at the University of

Michigan Library; Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler and Mary Ann

Bamberger of the Manuscript Collection, University of Illinois

at Chicago Circle; Charles P. LeWarne; Judge William J.

Wimbiscus of the State of Illinois Thirteenth Judicial Circuit;

Irene Moran and Diane Clardy of the Bancroft Library; Dr.

Josephine L. Harper and Miss Katherine S. Thompson of the

State Historical Society of Wisconsin; Archie Motley, Linda

Evans, Neal Ney, Larry Viskochil, John Tris, Julia Westerberg

and Miriam Blazowski of the Chicago Historical Society; the

staff of Newberry Library; and staff members of other libraries

too numerous to mention have assisted my research.

My thanks to the following for permission to use unpublished

material: the Illinois Labor History Society for permission to

quote from Lucy Parsons; Kathleen S. Spaulding for permission

to quote from George Schilling; University of Illinois at Urbana

for permission to quote from the Thomas J. Morgan Papers;

Houghton Library, Harvard for permission to quote from letters

by Dyer D. Lum, Carl Nold and Robert Steiner in the Joseph

Isbill Collection; the Bancroft Library for permission to quote

from the Thomas Mooney Papers; the Manuscript Collection,

University of Illinois at Chicago Circle for permission to quote

from the Ben L. Reitman Papers; the Washington State His

torical Society, Tacoma, Washington for permission to quote

from Thomas Bogard; Labadie Collection at the University of

Michigan Library for permission to quote from Agnes Inglis;

and the State Historical Society of Wisconsin for permission to

quote from the Albert R. Parsons Papers and the Knights of

Labor Collection.

The cover picture and the picture on page 12 are from the

1903 edition of The Life of Albert R. Parsons, courtesy of the

Chicago Historical Society.

July, 1976 Carolyn Ashbaugh

Preface

Lucy Parsons was black, a woman, and working class--three

reasons people are often excluded from history. Lucy herself

pointed out the class bias of history in 1905 when she criti

cized historians who had written about "the course of wars, the

outcome of battles, political changes, the rise and fall of

dynasties and other similar movements, leaving the lives of

those whose labor has built the world. . . in contemptuous

silence." The problem of piecing together Lucy Parsons' life

(1853-1942) from fragmentary evidence was more difficult

than the usual problem of writing about a working class rebel,

because the forces of "law and order" seized her personal papers

at the time of her death.

Even among histories by and about socialists, the work of

women has been largely ignored. On the left, the view of Lucy

Parsons as the "devoted assistant" of her martyred husband

Albert Richard Parsons is prevalent. Feminists who have for

gotten the radical working class roots of the feminist move

ment have also overlooked Lucy Parsons. Editors of the Rad

cliffe Notable American Women three volume work consigned

Lucy Parsons to their discard file on the grounds that she was

"largely propelled by husband's fate" and was "a pathetic

figure, living in the past and crying injustice" after the Hay

market Police Riot.

However, Lucy Parsons, a black woman, was a recognized

leader of the predominately white male working class move

ment in Chicago long before the 1886 police riot. Even Labor's

Untold Story, which offers a sympathetic although sentimental

account of Lucy, states that she became involved in the radical

movement only after her husband was sentenced to death and

then primarily to save his life. Lucy Parsons was not interested

in saving Albert Parsons' life. She was interested in emancipat

ing the working class from wage slavery. Lucy and Albert were

prepared-even eager-to sacrifice his life, believing his death

as a martyr would advance the cause. Lucy was eager to offer her

7

own life as well in the struggle for economic emancipation.

Only Howard Fast in The American, his fictionalized bio

graphy of John Peter Altgeld, has thus far captured the

strength, character and determination of Lucy Parsons.

The impression that Lucy Parsons devoted her life to clearing

her husband's name of the charge of murder is erroneous,

generated by the fact that when reporters heard her lecture they

stressed her connection to Albert Parsons and emphasized the

comparisons she made between the contemporary situation in

the labor movement and the events of 1886-1887. H Lucy spoke

for an hour and a half on the Sacco and Vanzetti case or the

Tom Mooney case, then alluded to the Haymarket case for 15

minutes, the newspapers reported that she had denounced the

police for murdering her husband in 1887. However, Lucy

Parsons was one of many labor radicals, liberals, and reformers

who connected each frame-up case with the legal precedent for

political conspiracy trials, the trial of the Haymarket "anarch

ists" in 1886.

On May 1, 1886, the city of Chicago had been shut down

in a general strike for the eight hour working day-the first

May Day. On May 4, the police broke up a meeting in Hay

market Square that had been called to protest police brutality.

Someone threw a bomb, and the police began shooting wildly,

fatally wounding at least seven demonstrators. Most of the

police casualties resulted from their own guns. Eight radical

leaders, including Albert Parsons, were brought to trial for the

bombing. All the prosecution had to prove was that the men on

trial were the same men who had been making speeches on the

lakefront and publishing the radical workers' papers the Alarm

and Arbeiter-Zeitung. The court ruled that although the defend

ants neither threw the bomb nor knew who threw the bomb,

their speeches and writings prior to the bombing might have

inspired some unknown person to throw it and held them "ac

cessories before the fact" in the murder of policeman Mathias

Degan. All eight were convicted, and on November 11, 1887,

Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George

Engel were hanged.

Lucy Parsons remained active in the radical labor movement

for another 5 5 years. She published newspapers, pamphlets, and

books, traveled and lectured extensively, and led many demon-

8

strations. She concentrated her work with the poorest, most

downtrodden people, the unemployed and the foreign born.

She was a member of the Social Democracy in 1897, a founding

member of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, and

was elected to the National Committee of the International

Labor Defense in 1927.

Lucy Parsons was a colorful figure whose style was to capture

headlines. She had a commanding appearance-tall, dark, and

beautiful, a beauty which turned to a mellow, peaceful expres

sion as she aged-and a tremendous speaking voice which

captivated audiences with its low musical resonance. Lucy was a

firebrand who spoke with terrifying intensity when the occasion

demanded it.

Lucy's struggle with the Chicago police for free speech lasted

for decades. Police broke up meetings only because the speaker

was Lucy Parsons; they dealt with her in an aggressive and

unlawful manner, systematically violating her right to free

speech and assembly. Although Lucy was hated by the police,

Chicago liberals often came to her assistance. In about 1898

Graham Taylor of the Chicago Commons Settlement House

arranged for her to speak at the settlement's Free Floor Forum

without police harrassment. When Lucy was arrested while

leading a Hunger Demonstration in 1915 Jane Addams of Hull

House arranged her bail. Deputy Police Chief Schuettler de

nounced Addams and linked the two women: "If Miss Addams

thinks it is all right for an avowed and dangerous anarchist

like Lucy Parsons to parade with a black flag and a band of

bad characters, I suggest that she go ahead and preach the

doctrine outright.''

By portraying Lucy Parsons as a criminal, the police and

newspapers tried to direct public attention away from the real

issues which Lucy was trying to raise: unemployment and

hunger. Irwin St. John Tucker, the young Episcopalian minister

and socialist who was arrested with Lucy in 1915, recently re

called, "Lucy Parsons wasn't a hell-raiser; she was only trying

to raise the obvious issues about human life. She was not a

riot-inciter, though she was accused of it. She was of a religious

nature." "Friar Tuck" found Lucy a likeable and compelling

person.

Lucy Parsons' life energy was directed toward freeing the

9

working class from capitalism. She attributed the inferior posi

tion of women and minority racial groups in American society

to class inequalities and argued, as Eugene Debs later did, that

blacks were oppressed because they were poor, not because they

were black. Lucy favored the availability of birth control in

formation and contraceptive devices. She believed that under

socialism women would have the right to divorce and remarry

without economic, political and religious constraints; that women

would have the right to limit the number of children they would

have; and that women would have the right to prevent "legal

ized" rape in marriage.

Lucy Parsons' life expressed the anger of the unemployed,

workers, women and minorities against oppression and is ex

emplary of radicals' efforts to organize the working class for

social change.