Table Of ContentDigitized by the Internet Archive

in 2018 with funding from

Kahle/Austin Foundation

https://archive.org/details/ithou00bube_0

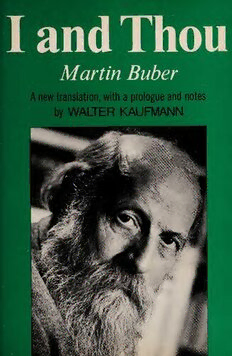

I AND THOU

t.

I AND THOU

Martin Buber

A NEW TRANSLATION

WITH A PROLOGUE “I AND YOU”

AND NOTES

BY

WALTER KAUFMANN

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

NEW YORK

Translation

Copyright © Charles Scribner’s Sons

1970

Introduction

Copyright © Walter Kaufmann

1970

All rights reserved. No part of this book

may be reproduced in any form without the

permission of Charles Scribner’s Sons.

192123252729 C/C 302826242220

23252729 C/P 30282624

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number

72-123845

SBN - (trade cloth)

684 10044-4

SBN - (trade paper, SL)

684 71725-5

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments 1

Key 5

I AND YOU: A PROLOGUE by Walter Kaufmann 7

A Plan Martin Buber Abandoned 49

Martin Buber’s I AND THOU 51

First Part 53

Second Part 87

Third Part 123

Afterword 169

Glossary 183

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present volume owes its existence to Rafael Buber.

In June 1969 he phoned me from Boston, explained that

he was Martin Buber’s son, and asked whether he could

come to see me in Princeton. We had never met, and he

offered no explanation; but when he came a few days later,

there was an instant rapport, coupled with an intriguing

lack of directness. He told me of his desire for a new

English translation of Ich und Du and asked my counsel.

I recalled how his father had told me that he considered

Ronald Gregor Smith, who had done I and Thou, by far his

best translator. Rafael insisted that those whose advice he

valued were agreed that the old version had to be replaced.

I myself had attacked the use of “thou” instead of “you”

in print, but at this point did not let on that I did not like

the old translation. Instead I pointed out how nearly un¬

translatable the book was. Rafael did not protest, but his

mind was made up, and he wanted my help. I mentioned

names. They would not do: the new version had to be done

by someone who had been close to his father; and he had

come a long way and did not want to return home to Israel

without having accomplished this mission. Now I insisted

that the book really was untranslatable, and that all one

2 I AND THOU

could do was to add notes, explaining plays on words—and

I gave an example. Instant agreement: that was fine—a

translation with notes. He wanted me to do it, however I

chose to do it, and it was clear that I would have his full

cooperation.

This I got. That unforgettable day in my study, and later

on in the garden, was the fourth anniversary of Martin

Buber’s death. I hesitated for a few days, but the challenge

proved irresistible. Thus I was led back into another dia¬

logue with Martin Buber, well over thirty years after I had

first seen and heard him in Lehnitz (between Berlin and

Oranienburg) where he had come with Ernst Simon at his

side to teach young people Bibel lesen—to read the Bible.

In the summer of 1969 I visited the Buber Archive in

Jerusalem and had a look at the handwritten manuscript of

Ich und Du and at Buber’s correspondence with Ronald

Gregor Smith. I asked for copies of the complete manu¬

script and of all pages on which Buber had commented on

points of translation. The material was promptly sent to

me and turned out to be of considerable interest. (See the

Key, below.) Having noticed some discrepancies between

the first edition of the book and the later editions, I asked

Rafael Buber whether he had a record of the variants. He

did not, but made a list himself, by hand, for my use.

Both from him and from Mrs. Margot Cohn, who for

decades was Buber’s secretary and who now works full¬

time in the Archive, I have encountered not only kindness

and cooperation at every point but the spirit of friendship.

I have been equally fortunate with my undergraduate

research assistant at Princeton, Richard L. Smith ’70. He

had read the original translation of I and Thou three times

before he began to assist me, and he loved the book. There

is no accounting for how many times he has read it now,

comparing the new version with the old one, raising ques-