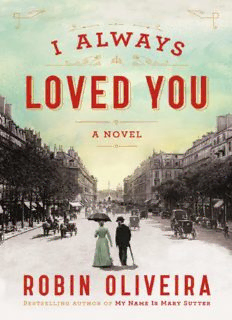

Table Of ContentAlso by Robin Oliveira

My Name Is Mary Sutter

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Robin Oliveira Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free

speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws

by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing

Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

ISBN: 978-1-10160488-5

This is a work of fiction based on real events.

Version_1

For Noelle and Miles

Contents

Also by Robin Oliveira

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1926

Prologue

1877

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

1878

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

1879

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

1880

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

1881–1883

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

The Rest of Time

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

1926

Prologue

M

ary Cassatt lifted two shallow crates of assorted brushes, pigments,

palettes, and scraping knives and set them atop the paint-smeared table

shoved under the arched, north-facing windows of her untidy studio. Someone

less stubborn than she might have packed up years ago, but she liked to have her

tools out and ready, as if at any moment she might turn and begin again, though

she had not painted today and would not paint tomorrow and had not painted in

some years, the scourge of the continuing betrayal of her eyesight, which she

feared had become nearly as bad as his at the end. And then there was the pesky

matter of confidence, which she’d discovered, to her disappointment, had not

solidified over the years as her younger self had expected but had instead

revealed itself to be an emotion that was more ruse than intention. The truth was

that there was very little she could control anymore, except this one last thing,

which made her feel very old.

She turned in a circle, suppressing the unfamiliar swell of panic rising in her

throat, an emotion to her so exotic that she wondered how other people—those

who yielded daily to weakness or fear—coped.

Oh, where was the damn thing?

She was certain she’d hidden the box among the blank canvases and tin

water cans, where no one, not even a sly model bent on discovery, would have

guessed she’d secreted the prize. But she was not as keen as she had once been

and now feared that both her eyesight and her memory may have double-crossed

her. Had she, in a fit of sentiment, concealed it somewhere upstairs in her

bedroom in order to keep it close? She dismissed the thought. She could not

imagine herself committing such a romantic act.

Daily, light flooded the stone-floored glassed-in studio at the back of the

Château de Beaufresne, but now the winter afternoon was fading and her eyes

were succumbing to fatigue. Time evaporating. The doctors said she was to

prepare herself, meaning, she supposed, that they wanted her to sell her

remaining canvases, attend to museum requests, visit relatives one last time—

what people imagined had been her life. It mystified her that that was what they

all thought was important to her. Of course she valued her work, and she had

kept careful track as the prices for her paintings rose—prudence required such

attention—but did they suppose that in touching brush to canvas she tallied only

coin and admiration?

The world blazes along with its critical tongue and shallow impatience, not

understanding the moment, the breath, the seeing.

She adjusted her thick-lensed glasses. What a necessary bother they were.

Such goggles, but it was true that if she were still as careful a housekeeper of her

studio as she had been in her youth, she could find what she wanted in an instant.

What detritus a life leaves. She would have to call Mathilde to help her if she

couldn’t find it. Look for shape, she scolded herself. The thing is not the thing. It

is instead form and light. After all, what are faces but hollows and swells,

spheres and lines? She had learned that very young. And now? She removed her

glasses and wiped her watering eyes. Oh, to see as she once had. Some mornings

upon waking, she indulges herself: Today I will paint the lace on the dress, finish

the flowers in the background, and then concentrate on the way the sun plays on

the girl’s hair. And then she opens her eyes, and a milky scrim obscures even

the bedposts.

Mary replaced her glasses and willed her blurring eyes to focus on the

jumble of brushes and palette knives and dismantled easels. Under this

purposeful gaze, their forms sharpened and fell away and became the contour

and outline she needed them to be. For half a century, she had shifted sight like

this at will, though when she was young, when she was first beginning to paint,

the effort had pained her. It is a way of thinking, her instructors had said. It is a

way of being in the world.

And with that shift, the half-moon shape of the box revealed itself,

protruding from under the edge of the tarpaulin. Kneeling, she felt its rounded

edge and exhaled. Tucking it under her arm, she shuffled to the far end of the

room, where Mathilde had left the tea tray for her on the table by the hearth,

along with the magnifying glass she required.

Mary sank into the chair and opened the lid. It was the kind of box that

harbors forgotten photographs or mismatched buttons, so ordinary that after her

death they might have tossed it without checking the contents, but she couldn’t

take that chance. And besides, their curiosity had dogged her all her life; she

would not let it dog her death. She was not sentimental, though people believed

she was, seduced perhaps by the expressions she had rendered in her paintings.

But she didn’t know, really, what people thought of her. And she didn’t care.

Her work, like his, was all the legacy she cared to bequeath to the world.

But she had kept these letters, as he had kept hers, though what they had