Table Of ContentTo Nic, for leading me to

the Rabbit Hole

Acknowledgments

• • •

I

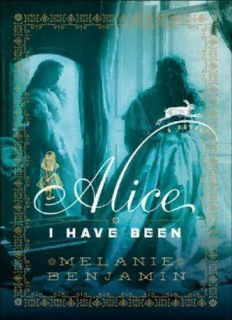

have been written without one person’s

T’S NOT OFTEN AN AUTHOR CAN SAY A BOOK TRULY WOULDN’T

influence, but Alice I Have Been would never have come about were it not for

my dear friend and writing partner, Nicole Hayes. Gratitude doesn’t even

come close to expressing how I feel about her, but it will have to do.

My wonderful agent and friend, Laura Langlie, must also be thanked for

her support, dedication, and unwavering belief. To Kate Miciak, the most

enthusiastic, understanding, terrifyingly smart editor ever—thank you for

loving Alice as much as you do.

I also have to thank Nita Taublib, Randall Klein, Loyale Coles, Carolyn

Schwartz, Quinne Rogers, Susan Corcoran, Loren Noveck, and everyone else

at Bantam Dell who has done so much for Alice and me. Also thanks to Peter

Skutches, Tooraj Kavoussi, and Bill Contardi.

Judy Merrill Larsen and Tasha Alexander also deserve a big thank-you for

putting up with my authorly angst.

Karen Schoenewaldt at the Rosenbach Museum and Library and Matthew

Bailey at the National Portrait Gallery in London were very helpful in my

search for images of Alice Liddell. I am also indebted to several books and

websites concerning Alice Liddell and Charles Dodgson. The Other Alice by

Christina Björk and Inga-Karin Eriksson (a charming picture book), The Real

Alice by Anne Clark, and The Lives of the Muses by Francine Prose helped

immensely in establishing biographical facts about Alice Liddell and her

family. I found the website “Alice in Oxford” (http://www.aliceinoxford.info)

to be very helpful as well. Also the Lewis Carroll home page

(http://www.lewiscar roll.org/carroll.html), operated by the Lewis Carroll

Society of North America, was useful, as was the site for the UK Lewis

Carroll Society (http://lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk/index.html). The Life of

John Ruskin by W. G. Collingwood was also of help.

Of course, I could not have written this book without rereading Lewis

Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.

Finally, I have to acknowledge my family—Pat and Norman Miller, Mark

and Stephanie Miller, Mike and Sherry Miller; thank you all for the support

and good wishes.

And as always, my love to Dennis, Alec, and Ben. Without you, none of

this matters.

, 1932

CUFFNELLS

• • •

But oh my dear, I am tired of being Alice in Wonderland. Does it sound ungrateful? It is. Only I do get tired.

O

.

NLY I DO GET TIRED

I pause, place the pen down next to the page, and massage my aching hand;

the joints of my fingers, in particular, are stiff and cold and ugly, like knots

on a tree. One does get tired of so many things, of course, when one is eighty,

not the least of which is answering endless letters.

However, I cannot say that, not to my own son. Although I’m not entirely

sure what I am trying to say in this letter to Caryl, so kindly inquiring as to

my health after our hectic journey. He accompanied me to America,

naturally; if I’m being completely truthful, I would have to admit my son was

much more excited about the prospect of escorting Alice in Wonderland

across the ocean than Alice herself was in going.

“But Mamma,” he said in that coy way—entirely ridiculous for a man of

his age, and I told him so. “We—you—owe it to the public. All this interest

in Lewis Carroll, simply because it’s the centennial of his birth, and everyone

wants to meet the real Alice. An honorary doctorate from Columbia

University.” He consulted the telegram in his hand. “Interviews on the radio.

You simply must go. You’ll have a marvelous time.”

“You mean you’ll have a marvelous time.” I knew my son too well, knew

his strengths and his flaws, and unfortunately the latter outnumbered the

former, and they always had. When I thought of his brothers—

No, I will not. That is uncharitable to Caryl and painful to myself.

Surprisingly, when the time came I did have a marvelous time. So much

fuss made over me! Bands playing when the ship docked, banners

everywhere, even confetti; endless photographs of me drinking tea—so

tedious, but the Americans simply could not get enough of that. Alice in

Wonderland at a tea party! Imagine! It was a miracle they didn’t ask Caryl to

dress up as the Mad Hatter.

However, to be feted by scholars—it took me back, in such an unexpected

way, to my childhood, to Oxford. I hadn’t realized how much I’d missed the

stimulating atmosphere of academia, the pomp and circumstance, the endless

arguments that no one could win, which was never the point; the point was

purely the love of discourse, the heat of the battle.

Shockingly—and despite what I had been warned—I found everyone in

America to be perfectly charming, with the exception of one unfortunate

youth who offered me a stick of something called “chewing gum” just prior

to the ceremony at Columbia. “What does one do with it?” I inquired, only to

be told, simply, to chew. “Chew? Without swallowing?”

A nod.

“To what end? What possibly could be the point?”

The young man could not answer that, and withdrew his invitation with a

sheepish smile.

Still, what was truly tiresome—what is always truly tiresome—was the

disappointment, brief and politely suppressed, evident in all the faces. The

disappointment of looking for a little girl, a bright little girl in a starched

white pinafore, and finding an old lady instead.

I understand. I myself suffer it each time I consult a looking glass, only to

wonder how the glass can be so cracked and muddled—and then realize, with

a pang of despair, that it is not the glass that is deficient, after all.

It is not merely vanity, although I admit I have more than my fair share of

this conceit. Other elderly dowagers, however, were not immortalized in print

as a little girl, and not merely as a little girl but rather as the embodiment of

Childhood itself. So they are not confronted by people who ask, always so

very eagerly, to see “the real Alice”—and who cannot hide the shock, the

disbelief, that the real Alice has not been able to stop time.

So, yes, I do get tired. Of pretending, of remembering who I am, and who I

am not, and if I sometimes get the two confused—much like the Alice in the

story—I may be excused. For I am eighty.

I am also tired of being asked “Why?”

Why did I sell the manuscript, the original version of Alice’s Adventures

Under Ground, printed by Mr. Dodgson just for me? (Lewis Carroll I did not

know; they are merely words on a page—written by Lewis Carroll. They

have nothing to do with the man I remember.)

Why would the muse part with the evidence of the artist’s devotion? Even

Americans, with their eagerness to put a price on everything, could not

understand.

I look out the windows—the heavy leaded-glass windows, not as sparkling

as I would wish; I’ll have to speak to Mary Ann about that—of my sitting

room, which overlooks the lush, heavily forested grounds of Cuffnells. Today

the clouds are low, so the tempting glitter of the Solent is hidden from view. I

can see the lawn where the boys played, Alan and Rex (and yes, Caryl); the

pitch where they played cricket; the paths where they first learned to ride and

where they strode home with their first stag, accompanied by their father, so

very proud—and I know I made the only decision possible. This place, this is

my sons’ childhood, their heritage, and it’s all I have left.

The other, the simply bound manuscript posted to me one cold November

morning, long after the golden afternoon of its creation—that was my

childhood. Only it had never truly belonged to me; Mr. Dodgson, of all

people, understood that.

The clock on the mantel chimes twice; how long have I been sitting here

staring out the window? The ink on the nib of my pen has dried. I find myself

doing such idle, silly things so often these days, these days when my thoughts

scatter like billiard balls into their respective pockets, these days when I am

so very tired, unaccountably weary; I even find myself dozing off at the

oddest moments, such as teatime, or late mornings when I should be going

over accounts.

Simply contemplating my eternal weariness provokes a yawn, and I look

longingly at the chaise in the corner, with its faded red afghan thrown over

the arm. I manage to stifle the yawn and tell myself sternly that it is only two

o’clock, and there is much to do.

I fold the letter to Caryl neatly in thirds; I’ll finish it later. I open my desk

drawer and remove a stack of letters bound with a worn black silk ribbon,

letters that I have begun and not finished, for various reasons. I have learned,

through the years, it is the letter not sent that is often the most valuable.

There, right on top, is the letter I began almost two years ago:

Dear Ina,

I received your kind letter of Tuesday last—

And that is all I have managed to write. Ina’s kind letter of Tuesday last

also is within this bundle; I remove it, adjust my spectacles (really, the

indignities of age are most trying), and peruse it once more.

I suppose you don’t remember when Mr. Dodgson ceased coming to the Deanery? How old were you? I said his manner became too affectionate toward you as you grew older and that

Mother spoke to him about it, and that offended him so that he ceased coming to see us again, as one had to give some reason for all intercourse ceasing—

This is the letter that I long to answer, not the one from Caryl kindly

inquiring as to my health. No, this letter, this ghost missive from my sister,

dear Ina, dead now two years, almost. Yet the muddled memories she stirred

up—the memories she always managed to stir up, or manufacture, as if she

were a conjurer or a witch instead of a perfect Victorian lady—will not die

with her.

Will they die with Alice? I often wonder. Before I am gone from this earth,

before my bones lie in the churchyard, so far away from where those other

bones lie, I do hope that others’ memories will finally fall away and I will be

able to remember, with a clarity of my very own, what happened that

afternoon. That seemingly lovely summer afternoon, when between the two

of us, we set out to destroy Wonderland—my Wonderland, his Wonderland

—forever.

So yes, I do get tired; tired of pretending to be Alice in Wonderland still,

always. Although it has been no easier being Alice Pleasance Hargreaves.

Truly, I wonder; I have always wondered—

Which is the real Alice, and which the pretend?

Oh dear! I’m sounding like one of Mr. Dodgson’s nonsense poems now.

He was so very clever at that sort of thing; much cleverer than I, who never

had the patience, not then, not now.

I remove my spectacles; massage the bridge of my nose where they pinch.

My head is throbbing, threatening, and I do not like being in this state. The

journey was exhausting, if I’m being entirely truthful. I am tired of being

Alice, period; yet my memories will not let me rest, not as long as I’m

reading through old letters, which is the surest sign yet that I have become a

doddering old fool.

The chaise looks so inviting; it’s such a cold afternoon.

Perhaps I will lie down, after all.