Table Of ContentTHE

ARAB

MIND

revised edition

Also by Raphael Patai

The Poems of Israel B. Fontanella (in Hebrew), 1933

Water: A Study in Palestinian Folklore (in Hebrew), 1936 Jewish Seafaring in Ancient Times (in Hebrew), 1938

Man and Earth in Hebrew Custom, Belief and Legend (in Hebrew), 2 vols., 1942-1943

Historical Traditions and Mortuary Customs of the Jews of Meshhed (in Hebrew), 1945

The Science of Man: An Introduction to Anthropology (in Hebrew), 2 vols., 1947-1948

Man and Temple in Ancient Jewish Myth and Ritual, 1947, 1967 On Culture Contact and Its Working in Modern Palestine, 1947

Israel Between East and West, 1953, 1970

Jordan, Lebanon and Syria: An Annotated Bibliography, 1957 The Kingdom of Jordan, 1958, 1984

Current Jewish Social Research, 1958

Cultures in Conflict, 1958, 1961

Sex and Family in the Bible and the Middle East, 1959

Golden River to Golden Road: Society, Culture and Change in the Middle East, 1962, 1967, 1969, 1971

Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis (with Robert Graves), 1964, 1966 The Hebrew Goddess, 1967, 1978, 1990

Tents of Jacob: The Diaspora—Yesterday and Today, 1971 Myth and Modern Man, 1972

The Arab Mind, 1973, 1976, 1983

The Myth of the Jewish Race (with Jennifer P. Wing), 1975, 1989 The Jewish Mind, 1977, 1996

The Messiah Texts, 1979

Gates to the Old City, 1980, 1981

The Vanished Worlds of Jewry, 1980

On Jewish Folklore, 1983

The Seed of Abraham: Jews and Arabs in Contact and Conflict, 1986 Nahum Goldmann: His Missions to the Gentiles, 1987 Ignaz

Goldziher and His Oriental Diary, 1987

Apprentice in Budapest: Memories of a World That Is No More, 1988 Between Budapest and Jerusalem, 1992

Journeyman in Jerusalem, 1992

Robert Graves and the Hebrew Myths, 1992

The Jewish Alchemists: A History and Source Book, 1994 The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology, 1995 Jadıd al-Islm:

The Jewish “New Muslims” of Meshhed, 1997 Arab Folktales from Palestine and Israel, 1998

The Children of Noah: Jewish Seafaring in Ancient Times, 1998

RAPHAEL PATAI

THE

ARABMIND

With an Updated Foreword by Norvell B. De Atkine

Recovery Resources Press

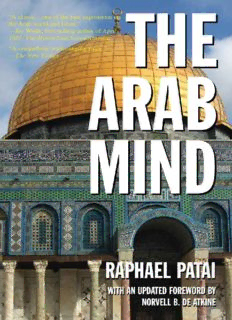

The Arab Mind

A Recovery Resources Press Book

© Copyright 1973, 1976, 1983, 2002, 2007 the estate of Raphael Patai Originally published in 1976, revised in 1983, and republished in

2002. ©©©©©2007 Foreword by Norvell B. De Atkine

©Cover Photograph 2010 Jennifer Schneider

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Recovery Resources Press PMB 372

7272 E. Broadway

Tucson, AZ 85710

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Patai, Raphael, 1910-1996

The Arab mind / Raphael Patai. — Rev. ed. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9672015-5-9

1. Arabs. I. Title.

DS36.77.P37 2007

305.892'7—dc22

2007018379

Cover Design by Angel Harleycat and Deborah Miller Interior Design and Layout by Fatema Tarzi

10987654321

Printed in the United States

The author wishes to express his thanks for permission to quote from the works listed below: Abram Kardineret al., The Psychological

Frontiers of Society, Columbia University Press, NewYork, 1945 ∑al˛ al-Dın al-Munajjid,A ‘midat al-Nakba: Bahth ‘Ilmı fı Asbb

Hazımat 5 Khazırn, Dr al-Kitb al-Jadıd (The

New Publishing House), Beirut, 1967

Nsir al-Dın al-Nashshıbı,Tadhkirat ‘Awda, Al-Maktab al-Tajjrı (The Trading Office), Beirut, 1962 Franco Nogueira,A Luta Pelo

Oriente, Junta de InvestigaçΩes do Ultramar, Ministerio do Ultramar, Lisbon, 1957 J.G. Peristiany (ed.),Honor and Shame: The Values

of Mediterranean Society, The University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, 1966

Constantine K. Zurayq,Ma’n al-Nakba Mujaddad,Dr al-’Ilm lil-Malyın, Beirut, 1967

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY NORVELL B. DE ATKINE X PREFACE TO THE 1983 EDITION XXII

PREFACE TO THE 1976 EDITION XXV PREFACE: ON A PERSONAL NOTE 1 A NOTE ON

TRANSLITERATION 8

I THE ARABS AND THE WORLD 9 1. Islam, Middle East, Arabs 9 2. Who Is an Arab? 12

II THE GROUP ASPECTS OF THE MIND 16

III ARAB CHILD-REARING PRACTICES 26

1. The Issue of Severity 26

2. Differential Evaluation of Boys and Girls 28

3. Lactation 31

4. Early Roots of the Male-Female Relationship 34

5. The Boy Enters the Men’s World 35

6. The Girl Remains in the Women’s World 37

7. Childhood Rewards and Adult Achievement 38

—

MvM

—

IV UNDER THE SPELL OF LANGUAGE 43

1. Arab and Arabic 43

2. The Lure of Arabic 46

3. Rhetoricism 50

4. Exaggeration, Overassertion, Repetition 52

5. Words for Actions 63

6. Time Sense and Verb Tense 69

V THE BEDOUIN SUBSTRATUM OF

THEARAB PERSONALITY 78 1. The Bedouin Ideal 78 2. Group Cohesion 83

VI BEDOUIN VALUES 89

1. Hospitality 89

2. Generosity 92

3. Courage 94

4. Honor 95

5. Self-Respect 100

VII THE BEDOUIN ETHOS AND

MODERN ARAB SOCIETY 103

1. Koranic and Folk Ethics 103

2. Wajhor “Face” 108

3. Shame 113

4. The Fahlawı Personality 113

5. Aversion to Physical Labor 120

VIII THE REALM OF SEX 126

1. Sexual Honor 127

2. Sexual Repression 136

3. Sexual Freedom and Sexual Hospitality 140

4. Varieties of Sexual Outlet 143

5. Ambivalence and Change 147

—

MviM

—

IX THE ISLAMIC COMPONENT OF

THE ARAB PERSONALITY 152

1. Religion East and West 152

2. Predestination and Personality 156

3. Improvidence 160

X EXTREMES AND EMOTIONS,

FANTASY AND REALITY 165

1. Polarization 165

2. Control and Temper 169

3. Hostility 171

4. Three Functional Planes:

Thoughts, Words, Actions 172

XI ART, MUSIC, AND LITERATURE 177

1. Decorative Arts 177

2. Music 180

3. Literature 185

4. Toward Western Forms 187

XII BILINGUALISM, MARGINALITY,

AND AMBIVALENCE 190

1. Bilingualism and Personality 190

2. Marginality 199

3. Cultural Dichotomy: Elites and Masses 204

4. Ambivalence 209

5. Izdiwj—Split Personality 212

XIII UNITY AND CONFLICT 216

1. The Idea of Arab Unity 216

2. Fighting: Swords and Words 221

3. Dual Division 228

4. Conflict Proneness 232

—

MviiM

—

XIV CONFLICT RESOLUTION

AND “CONFERENTIASIS” 241 1. Conflict Resolution 241 2. “Conferentiasis” 252

XV THE QUESTION OF ARAB STAGNATION 261

1. The Message of History 261

2. Critical Views 263

3. Where Do We Go from Here? 266

4. Stagnation and Nationalism 269

5. Five Stages 271

6. The Enemy as Exemplar 273

XVI THE PSYCHOLOGY

OF WESTERNIZATION 284

1. The Jinni of the West 284

2. Egypt—A Case History 286

3. The Issue of Technological Domination 291

4. Focus, Values, and Change 295

5. Five Dominant Concerns 299

6. Western Standards and Mass Benefits 305

7. The Sinister West 308

8. The Hatred of the West 314

9. Arabs and Turks 319

10. Facing the Future 322

CONCLUSION 326

POSTSCRIPT 1983 333

1. The Reaction to the October War 333

2. Oil, Labor, and Planning 340

3. Advances in Education 345

4. Women’s Position 347

5. New Conflicts 356

—

MviiiM

—

6. The Quest for Unity 359

7. The Federation of Arab

Republics: A Case History 365

8. Conclusion 373

TABLES

1. The Arab World: Area and

Mid-Year Population Estimates 379

2. Gross School Enrollment Ratios in Arab Countries for Primary School Education 380

3. Gross School Enrollment Ratios in Arab Countries for Higher (Tertiary) Education 381

4. Population of Arab Countries by Sex (in Thousands) in 2005 382

5. Birth Rates in Arab Countries (Live Births per Year per 1,000 Population) 383

6. Literacy Rates in Arab Countries 384

7. Female School Enrollment in Arab Countries 385

8. Quality of Life Index 386

APPENDIX I

The Judgment of Historians: Spengler and Toynbee 387

APPENDIX II

The Arab World and Spanish America: A Comparison 398

NOTES 403

INDEX 447

ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND CONTRIBUTOR 465

FOREWORD

Congratulations are due on the reprinting of this much needed and incisive study of Arab culture. In

particular, these congratulations are warranted given the avalanche of ill-informed or sometimes

malicious aspersions cast upon this seminal work. Not only is TheArabMindone of the finest books

ever written on Arab culture, it is the only one in English that delves deeply into the culture, character,

and personality of the Arab people.

Much of this new wave of criticism has been based on the 2004 New Yorkerarticle written by Seymour

Hersh on the mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners at theAbu Ghraib prison; a passing comment from an

unidentified source about Raphael Patai’sTheArabMindled some journalists and academics to

conclude thatTheArabMindwas being used by the military as some sort of torture manual. Such a

ludicrous proposition could only be ascribed to a political agenda—or to sheer ignorance. The

incidents atAbu Ghraib were a result of ill-trained and substandard soldiers combined with a

breakdown of discipline and incompetent leadership. It was an aberration in the model performance

of American soldiers in Iraq in the most trying of conditions. This fact, however, did not deter the

critics and our enemies within and without who were determined to turn this controversy into a cause

célèbre. Unfortunately, defenders of Patai’s book have been noticeably quiet, so powerful is the

demand for conformity to group-think that for some years has constricted academic work in area

studies, especially when the area is as controversial a one as the Middle East.

Reading the various articles dismissive of TheArabMind, one particular point stands out. In not one

critical review or article that I have read is there a single instance of anyone refuting, with

documentation,

—

MxM

—

any of the material in the book. Rather, the criticism is typically ad hominem, though as usual, name-

calling merely indicates the desperate nature of the attacks on the book and on Patai personally.

What exactly do critics find objectionable in the book? First, there seems to be a view that the title The

Arab Mind has some sort of sinister implication. As one critic of the book wrote, “It belongs to an old

tradition that classified races according to their ostensibly characteristic traits, a field pioneered by

19th-century European writers and shared by, among others, T.E. Lawrence.” Actually, Patai

anticipated this criticism and outlines, at various junctures in the book, the difficulties of examining

national character, noting that famous Arab scholars such as the 15th-century Maqrızı were well

aware of both an Arab national character and its variations in different countries. Patai writes:

To this day this latter factor causes one of the main difficulties for anybody who attempts to portray

the Arab mind. There seems to be no such thing as an Arab in the abstract. He is always, and has been

at least since the days of Maqrızı, an Iraqi Arab, a Syrian Arab, and so forth. These differences in

character have, in turn, led to the creation in many parts of the Arab world of local tendencies, which

frequently clash with the overall, larger ideal of all-Arab unity. (p. 24)

Raphael Patai writes of sensitive human subjects and behavior in a way understandable to all those

with an intelligent interest in Arab society, not just other anthropologists or sociologists. And like

scholars everywhere who study their own or other cultures, he must engage in a certain level of

generalization if his work is not to devolve into infinite particularities. But unlike many

anthropologists today, Patai was fluent in the language of the people. He began studying Arabic at the

age of 18 in Budapest, and continued in Breslau under the great Semitic linguist Carl Brockelmann;

thereafter, he lived for many years in Palestine. Patai writes coherently and with the clear purpose of

having the reader acquire a greater understanding of the many aspects of Arab culture, presenting

these facets in a way that demonstrates how these cultural components influence and shape what might

be described as a composite Arab personality.

No other writer, with the possible exception of the Iraqi sociologist Sania Hamady in The

Temperament and Character of the Arabs (1960), has even attempted to do such a thorough study of

the Arabs. The vast majority of works dealing with Arab culture are either shallow catalogues of Do’s

and Don’t’s or tendentious academic précis with very little utility for individuals whose work requires

them to deal with living people, not abstract theories. As much as I admire the unmatched erudition of

Bernard Lewis and the incisive writings of David PryceJones, their contributions to Middle East

scholarship lie in different fields. Bernard Lewis analyzes the impact of Islam and its historical

interaction with Western culture in classics such as What Went Wrong? (2002) and The Crisis of Islam

(2003). David Pryce-Jones, in his trenchant critique of Arab political culture, The Closed Circle

(1989), excels in depicting the Arabs’ reversion to tribal and kinship ties and the resulting inability to

establish the institutions required to form a successful modern democratic state.

The second frequently made objection to The Arab Mind is that the book dwells disproportionately on

sexuality. Despite the fact that Patai devotes a brief, 25-page chapter, “The Realm of Sex,” to this

subject, it has elicited angry denunciations in view of the sexual nature of the criminal acts committed

at Abu Ghraib prison. In Arab society the values of honor and shame are intertwined with sexuality

(always an area of human vulnerability) and for that reason there is a marked preoccupation with sex

and its regulation. Despite the sometimes shocking openness of sexual talk and the inventive Arabic

lexicon of sexual expressions, this remains a most explosive issue in Arab society. As pointed out by

Patai, the more repressive a society is of a basic human function, the more likely the people are to be

preoccupied with it. Patai illustrates this very well in his opening paragraph to the chapter with the

allegorical story of the pink elephant and the sorcerer’s apprentice (Chapter VIII, page 126). Certainly

there is no dearth of studies on these and related subjects by Arab scholars such as Hisham Sharabi,

Hmid ‘Ammr, Fatima Mernissi, and ‘Alı al-Wardı to substantiate Patai’s contentions.

In the Arab world today, the availability of cell phones, e-mail, web cams, and ubiquitous satellite

television enables young people to circumvent restrictions on sexual conduct, terrifying the arbiters

of morals, usually the local clergy who exploit this issue for political power. From my early years in

the Middle East in the late 1960s until the present day, it has been evident that even slight political

improve

—

MxiiM

—

ment in the role of women is likely to be accompanied by an increase in social restrictions and

repression. It is a moot point to question whether women are repressed because of cultural sexual

mores or whether the strict imposition of a sexual code of conduct is simply a way by which men

continue to exercise control over women.

Yet Patai was correct in noting that changes in women’s status carry enormous implications for Arab

society as a whole. As he wrote:

In the Arab world, to a much greater extent than in the West, the shaping and molding of the minds of

infants and children are in the hands of the mothers. . . . This being the case, any change that occurs in

the position of Arab women, in the chances and stimuli given them to develop their mental faculties,

will have an impact on the mind of the next generation that is under their tutelage. (pp. 347-48).

It has been my observation that women are indeed crucial agents of change in the Arab world. I have

always been impressed by their more progressive and enlightened thinking on the issues affecting

Arab society. This was particularly true of the Iraqi women with whom I worked in Baghdad from

June 2003 to January 2004. Far more sensible and realistic than the men, they are the key to cultural

and political change in their world.

This was punctuated for me by the sponsorship of a young Shi’a Muslim woman with whom I had

worked in Baghdad and who lived with my wife and me for several months as she applied for asylum

after having her life threatened by Saddamist thugs. Coming from a very typical middle class but

somewhat more liberal Iraqi family, she was, nevertheless, very much a representative of her culture.

As the months passed it was gratifying to watch how she emerged from her cultural cocoon and grew

increasingly independent. She went to work, rented her own apartment, obtained a driver’s license,

purchased a car, and became her own person. There is no doubt that the cultural bondage in which

women are held is one of the main causes of the stagnation of Arab society.

A third charge against The Arab Mind relies on the overworked term “stereotyping.” Typically made

by those who smart at a characterization they find negative, this charge would have it that Patai has

consigned all Arabs to a single cookie cutter form. As I mentioned earlier,

—

MxiiiM

—

using Patai’s own words, he neither infers nor implies that all Arabs react or behave in the same

manner. A reasonably intelligent reader would understand that Patai explores general traits of Arab

society, which may be more or less pronounced in various regions of the Arab world and in

Description:quite clear that the feeling of having demonstrated strength is for an Arab state a psychological particular feature of Arab child-rearing practices is concerned, there is indeed a Their cultural conditioning left them no woman, in actual confrontation, as an object of pleasure”:13 while Moulo