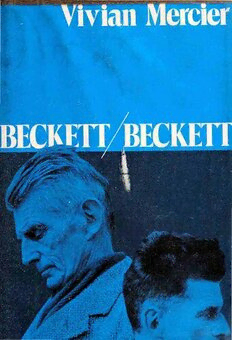

Table Of ContentBECKETT

BECKETT

VIVIAN MERCIER

New York / OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS / 1977

BECKETT / BECKETT

A Truth in art is that whose contradictory is also true.

OSCAR WILDE

Copyright © 1977 by Vivian Mercier

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-42658

Permission to use copyright material is hereby gratefully acknowledgcd:

To Les Editions de Minuit for the quotations in French from En attendant Godot, copy

right 1952 by Les Editions de Minuit; L'Expulse, copyright 1955 by Les Editions de

Minuit; Molloy, copyright 1951 by Les Editions de Minuit; Poemes, © 1968 by Les Edi

tions de Minuit.

To Faber and Faber, Ltd., for extracts from All That Fall, Eh Joe, Embers, Film, Footfalls,

Happy Days, Krapp's Last Tape, Play, That Time, Waiting for Godot, Words and Music,

all by Samuel Beckett; and from Our Exagmination . . . by Samuel Beckett and others.

To John Calder (Publishers) Ltd. for extracts from Malone Dies, Molloy, Poems in Eng

lish, Proust, Still, The Expelled, Three Dialogues with Georges Duthuit, The Unnamable,

Watt.

To Calder and Boyars, Ltd., for extracts from Enough and Ping (published in No's

Knife), First Love, HolV It Is, Lessness, The Lost Ones, Mercier and Camier, More Pricks

Than Kicks, Murphy.

To Grove Press, Inc., for extracts from Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces, copy

right © 1957 by Samuel Beckett, copyright © 1958, 1959, 1960 by Grove Press, Inc.; More

Pricks Than Kicks (The Collected Works of Samuel Beckett), all rights reserved (first pub

lished by Chatto and Windus, London, 1934); Happy Days, copyright © 1961 by Grove

Press, Inc.; Proust, all rights reserved, first published 1931; HolV It Is, copyright © 1964 by

Grove Press, Inc.; Ends and Odds, copyright © 1974, 1975, 1976 by Samuel Beckett; Film,

copyright © 1969 by Grove Press, Inc., Film (script) copyright © 1967 by Samuel Beckett;

Words and Music (from Cascando and Other Short Dramatic Pieces), copyright 1962 by

Samuel Beckett; Eh Joe, copyright © 1967 by Samuel Beckett; Play, copyright © 1964 by

Samuel Beckett; Murphy, first published 1938; Watt, all rights reserved; Poems in English,

copyright © 1961 by Samuel Beckett; Waiting for Godot, copyright © 1954 by Grove Press,

Inc.; Molloy, Malone Dies and The Un namable (from Three Novels), copyright © 1955,

1956, 1958 by Grove Press, Inc.; Endgame, copyright © 1958 by Grove Press, Inc.; The Lost

Ones, copyright© this translation, Samuel Beckett, 1972, copyright © Les Editions de

Minuit, 1970, originally published in French as Le Depeupleur by Les Editions de Minuit,

Paris, 1971; First Love and Other Shorts, copyright © this collection by Grove Press, Inc.,

1974, all rights reserved; Stories and Texts for Nothing, copyright © 1967 by Samuel

Beckett; Mercier and Camier, copyright © this translation, Samuel Beckett, 1974, copy

right © Les Editions -de Minuit, 1970, all rights reserved.

To New Directions Publishing Corp., New York, for quotations from James Joyce, Finne

gans Wake: A Symposium. Copyright Sylvia Beach 1929. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of Anlerica

To Eilis

PROLOGUE

(Spoken by the Author in his Own Person)

The second New York production of Waiting for Godot,

imported from Los Angeles, had an all-black cast: an early

proof of the universality of the play. On Friday nights dur

ing the run, the theater was turned into a seminar room

after the final curtain. A panel of "experts" - a psycho

analyst, an actor, an English professor, and so on - sat on

stage and conducted a dialogue with those in the auditorium;

admission was free. The night I attended this symposium,

the ITlOSt effective contribution was made by a member of

the audience who asked the panel the rhetorical question,

"lsn' t Waiting for Godot a sort of living Rorschach [ink

blot] test?" He was clapped and cheered by most of those

present, who clearly felt as I still do that most interpreta

e

tions of that play - indeed qf Samuel Beckett's work ..a s .. \..

whole - reveal more about the psyches of the people who

offer them than about the work itself or the psyche of its

author.

To this rule, if it is one, I don't profess to be an excep-

..

Vll

Vlll PROLOGUE

tion: on the contrary, the book that follows will be seen to

offer a rather personal view of its subject - though not, I

hope, a wildly idiosyncratic one. Not that I can claim any

special intimacy with Beckett the ·man: I have met him

only three times and, out of respect for his privacy, made

very few notes after these meetings. I have also received

about a dozen letters from him1 one or two of which might

be described as self-revelatory, but I have quoted only pas

sages that are factual and neutral in tone, and very few even

of those.'

What makes my view of Beckett personal is chiefly the

fact that, having attended the same boarding-school and

university as he did, I was constantly aware of him as some

not very much older than myself (thirteen years), from

on~

the same rather philistine Irish Protestant background, who.

had become the sort of avant-garde artist and critic that I

longed to be.

"

A brief chronicle of this long-distance relationship with

Beckett TIlay not be entirely without interest. Born in April

1919, I entered Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, in Sep

tember 1928, just over five years after Beckett's departure.

It was not until 1934, however, that I first heard of him;

the news must have made a great impression, for I have

kept its source ever since - a leaflet entitled "Old Portora

Union: Terminal Letter No. 35." The then Headmaster,

Rev. E. G. Seale, distributed his "letter" (dated July 1934)

to all present members of the school as well as ttold boys."

J.

Having mentioned a book by another alumnus, Chartres

Molony, Seale continued:

But Old Portorans seem to be going strong in the lit

erary world. S. B. Becket [sic] has now brought out a vol-

·

PROLOGUE IX

ume entitled "More Pricks than Kicks." It is described

as "A piece of literature rnen10rable, exceptional, the

utterance of a very modern voice." The Spectator

de~

voted a column of criticism, mostly favourable, to this

book. We must heartily congratulate its author on such a

reception to his first "vork of fiction. His "Proust" was

published a couple of years earlier.

Although is in Northern Ireland, so that the

~nniskillen

subsequent banning of More Pricks than Kicks in the Irish

Free State had no legal effect I noticed that the book

there~

did not turn up in the school library: Portora in those years

was just beginning to admit that it had been the alma

mater of Oscar \\Tilde and wanted no fresh notoriety. All I

could do was to look up the Spectator review and try to dis

cover what this strangely named book \vas about. (Any

Portora boy of that vintage would have recognized, as I did,

the allusion to the conversion of St. Paul: in the King

James Bible, the voice from Heaven says, ttl t is hard for

thee to kick against the pricks.") I also identified Beckett,

wrongly, as the captain in an old photograph of a cricket

first eleven. Our senior French master, S. B. Wynburne,

had been an exact contemporary and close academic rival

of Beckett at Trinity College, Dublin.

I myself entered Trinity in 1936 at the same age as

Beckett had done and was accepted by the same Dr.

tutor~

A ...A . Luce. Like Beckett, I read Honors French with Pro

fessor T. B. Rudmose-Brown; my other lIonors subject was

English;> which Beckett had also read for a time before giv

ing it up to concentrate on Italian. Facts like these explain

the emphasis on Beckett as a member of a

particular_soci:~tl

class and ethnic grouping, with a particular type of educa-

X PROLOGUE

tion, especially in Chapters 3 and 4 below. Beckett is

2,

unique, as we all are, but he has not descended from an

other planet. Irvin Ehrenpreis, in his exemplary life of

Swift, anxious like me to present his subject as neither a

deity nor a monster, has drawn a number of parallels be

tween the future Dean and his contemporaries, including

of course some of his fellow-undergraduates.

After the Trinity B.A., Beckett's and my paths in life

soon diverged sharply, but I remained constantly aware of

him. In '1938, while still an undergraduate, I read Kate

O'Brien's enthusiastic review of Murphy; when she men

tioned the novel again later in the year, I decided to spend

a quarter of my weekly allowance on the single copy of it

that had languished on Hodges Figgis's shelves for several

months. I fell in love with the book at once and reread it

every year until it was lost or stolen about 1945. By then I

had also read Proust, the essay on Joyce's Work in Progress,

•

and, under the watchful eye of a Trinity librarian, the

banned More Pricks than Kicks. Quite possibly my Ph.D.

thesis, for which I received a Trinity doctorate in Decem

ber 1945, was the first to pay serious attention, however

briefly, to Beckett's fiction. I had already praised Murphy

in print, in the Jan uary-March 1943 issue of the Dublin

Magazine, while reviewing Eric Cross's The Tailor and

Ansty;

... Irish literature for the past twenty years has re

mained in the backwater of dialect reportage. Joyce at

least mingled inlagination with his realisnl, but his suc

cessors have largely ignored the fantastic side of Ulysses.

Only during the last three or four years have two books

appeared which contain both Joyce's ingredients-Sam-